In the Venn diagram of Concordia grads who have booked soul legend Ben E. King for a campus benefit concert, produced scholarship on Moby-Dick endorsed by the Melville Society, and patented a technology used by NASA to grow plants in space, the overlap is Ed Rosenthal, BA 74.

The English Literature alum, who graduated from Sir George Williams University months before it merged with Loyola College to become Concordia, calls himself “a poor farmer’s son who got lucky, took advantage of every opportunity and worked his ass off.”

Rosenthal had to work hard by necessity. Born in New York in 1950, he moved to Lachute, Quebec, as a boy so his father — a farmer from Romania who witnessed his own father’s death at the hands of the Nazis — could tend a plot of land.

The adjustment to country life was difficult on Rosenthal and his mother, a cosmopolitan New Yorker. Anti-Semitism was rampant (the Rosenthals were the only Jews in the area) and the farm foundered. To put food on the table, his father branched out and opened Magasin Royale, a women’s garment shop.

“I watched my dad grind and struggle and felt completely helpless,” recalls Rosenthal. “Literature became my refuge in grade school when my mother introduced me to Dickens and Twain.”

Sir George ‘went to tremendous lengths’

After the family relocated to Saint-Laurent, Montreal, Rosenthal earned a full scholarship to study at Sir George Williams in 1968. The scholarship changed his life.

“With that money, I was able to help support my parents. The university went to tremendous lengths to accommodate me. I will never forget the compassion and generosity of Mervin Butovsky, the assistant dean for the Faculty of Arts.”

Because he used his scholarship to care for his parents, Rosenthal supported himself with part-time jobs at Morgan’s “Bon Marché” — where he met his future wife, Berthe (Betty) Hadida — and menswear store A. Gold & Sons in downtown Montreal.

He also distinguished himself on campus. The honours student wrote a heralded paper on Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, took courses in polymer chemistry — a fascination that would pay dividends later on — and became involved in student government.

Enter that Ben E. King benefit concert.

Ed Rosenthal, BA 74, and his company, Florikan, were inducted into NASA’s Space Technology Hall of Fame in 2017.

Ed Rosenthal, BA 74, and his company, Florikan, were inducted into NASA’s Space Technology Hall of Fame in 2017.

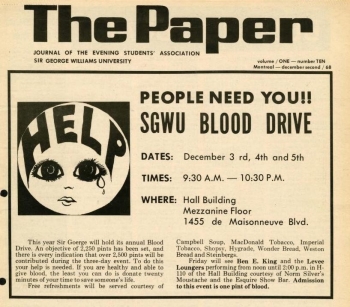

A campus blood drive organized by Rosenthal and his peers at Sir George Williams University was promoted in the journal of the evening students’ association.

A campus blood drive organized by Rosenthal and his peers at Sir George Williams University was promoted in the journal of the evening students’ association.

Rosenthal — pictured here with Gioia Massa, project scientist at NASA Kennedy Space Center, and Betty Rosenthal — “saved NASA years of research.”

Rosenthal — pictured here with Gioia Massa, project scientist at NASA Kennedy Space Center, and Betty Rosenthal — “saved NASA years of research.”