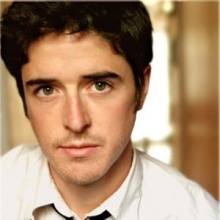

André Simoneau, this year’s fiction winner, has completed his second year in Concordia’s honours English and creative writing program. Trained in professional theatre at Montreal’s Dawson College, he has experience directing, screenwriting and acting as a TV host, enabling him to tell compelling and challenging stories through prose, theatre or film.

This excerpt from his Layton-award-winning short story Bridges We Build deals with lost friendships and the lengths we go to deal with regret.

André Simoneau

André Simoneau