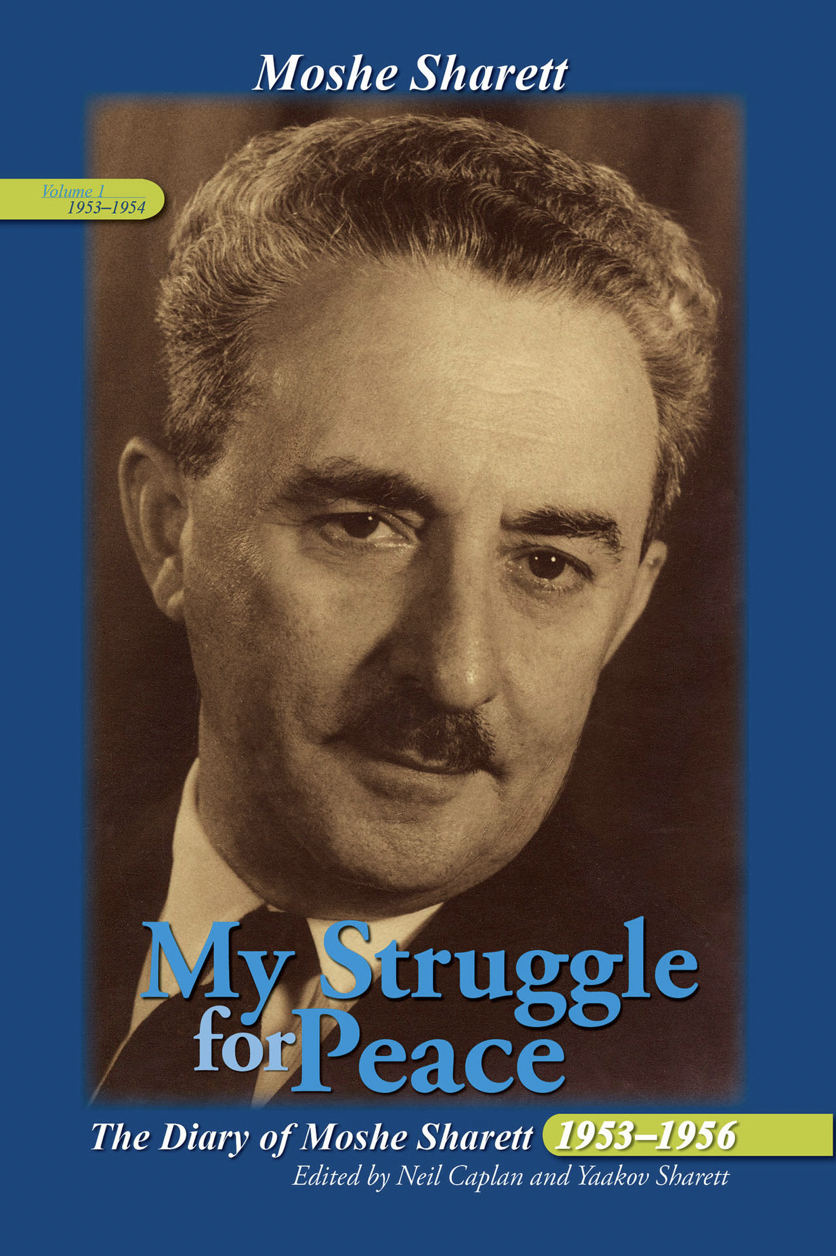

Reflections of Life, Loss, and Courage: The Diary of Moshe Sharett

By Randy Pinsky

“My Struggle for Peace” is the title of Moshe Sharett’s translated diary, and in itself, evokes the charged atmosphere of the period in which he was Israel’s first Foreign Minister. Readers catch a glimpse of a sensitive man, one committed to mediation and the peaceful development of his beloved Israel. It also reveals insecurity against those who felt his diplomatic approach was too ‘soft’; most prominently the fierce and fiery Prime Minister David Ben Gurion.

While less known than the iconic Moshe Dayan or the bespeckled Menachem Begin, Sharett made a mark of his own; the iconic dove to Ben Gurion’s hawk.

In sharing personal insights and heartbreaking deceptions of a political career cut prematurely short, readers are transported back to the world of a forgotten yet legendary Israeli politician.

There From the Start

Moshe Sharett’s son Yaakov (z’l 2022) was the keynote speaker of the Azrieli Institute and Friends of Ben Gurion University on April 11, 2016. As founder of the Moshe Sharett Heritage Society,[1] he was determined to make his father’s accomplishments and thoughts known. It took 16 painstaking years, but he and Montreal writer Neil Caplan translated and edited his many diaries, including his years as Israel's first Foreign Minister (1949-56).

“It is difficult to overstate the importance of those eight volumes to the study of the 1950s and to the understanding of Israeli history as a whole," noted Ha’aretz.

Born in 1894, Moshe Sharett and his family immigrated to Palestine in 1906, graduating from Israel’s first Hebrew high school. After attending the London School of Economics, he was enticed back to lead the political department of the Jewish Agency; the “almost-government” prior to statehood.

He would work alongside David Ben Gurion, Israel’s impatient yet extremely decisive first Prime Minister-to-be, as chief negotiator to the British administration, and “an important architect of Zionist policy.”

Common Goals, (Very) Different Approaches

When reading Sharett’s diary, the strain from interactions with Ben Gurion is evident. Counterpoint to Sharett’s cautious and methodological nature was the latter’s brash impulsiveness. While former Foreign Affairs Minister Abba Eban noted the two politicians often complemented one another (Caplan epilogue), it was often difficult to stand up against ‘the Old Man’.

This was particularly the case when Ben Gurion retired and Sharett was appointed the next Prime Minister (1954-55). It was difficult to fill the giant’s shoes, and it was a blow to his pride to see the visible relief when Ben Gurion returned.

Irreconcilable Differences?

As politicians, Sharett and Ben Gurion concurred on many critical policy issues, such as endorsing the 1947 United Nations partition proposal and declaring independence in May 1948 (in spite of American opposition), as well as German reparations following the Shoah (Holocaust).

Where they dramatically clashed was the possibilities for peace and means for addressing armed border incursions from Jordan, Gaza and Syria.

Sharett would play a pivotal role in the early stages of Israel, including campaigning the United Nations to adopt the partition plan; an act often overshadowed by the War of Independence and intentionally minimized by Ben Gurion. Sharett would confide in his diary, “I am a Hanukkah candle with no pretensions of competing with a neon light.”

Tensions at Sinai…and Not Just in the Battlefield

Problems would come to a head when Israeli military intelligence learned Egypt was receiving sophisticated weapons from the Soviet Union. Sharett “consistently opposed Ben Gurion’s increasingly uncompromising policies towards a belligerent Egypt…believ[ing] that [they] would result in an escalation of violence that was not in Israel's long-term interests.”

Tired of Sharett’s cautious diplomatic approach, Ben Gurion was adamant about the need for a preemptive attack. Ben Gurion believed that Sharett was a good foreign minister during peace – but not during wartime. He thus implemented measures to steadily force Sharett out.

Sharett’s wife Zipporah was only too aware of the complexities of the situation, and commented (perhaps with premonition), “[resignation] will be [a] fine [solution] for you personally, but…a catastrophe for the country.” He would ultimately leave the Knesset in 1956 (when Ben Gurion threatened to quit otherwise), confiding, “I felt that the die had been cast; I was stunned and probably showed it.”

A New Career

Sharett was restless in retirement, though appreciative of the newfound “freedom I have been given from the psychological shackles in which I have been bound for years.” He would go on to become a diplomat in Asia, nursing the wounds of his dismissal.

It was on mission in India that he would learn that Israel had attacked Egypt in a preemptive strike:

“This logic left me cold.…we are cutting off the branch on which we are perched.”

A Legacy to Remember

To many, Sharett is “a character from a kind of tragic romance.” The Jerusalem Post appraised his diary as "a unique human document… a treasure trove for the student of Israel's contemporary history and invaluable for the understanding of one of its crucial periods."

As noted by former Israeli Consul General Ziv Nevo Kulman, “Sharett’s legacy lives on, but…also…not…because Israel is still not at peace.”

Yet Moshe Sharett will always be remembered for his efforts at diplomacy and his rapport with Arab leadership.

Many wonder; what would the Middle East be like today had his moderate approach been adopted?

[1] Ironically located on Ben Gurion street…