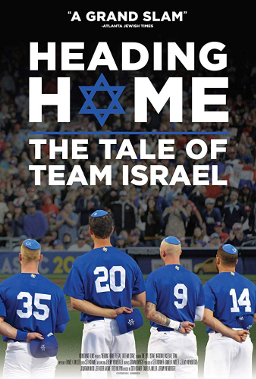

Photo Credit: IMDb

Israel and Sports: A Come-From-Behind Story

By Randy Pinsky

Team Israel is once again competing in the World Baseball Classic; Israel's Women's Hockey Team recently made global headlines, and the country regularly makes its mark in martial arts and gymnastics.

So sports have always been central to the Israeli and Jewish identity…right?

Not exactly, explained Dr. Ofer Idels, speaking on April 11 on “A Purposeless Spectacle: The Interwar Origins of Israeli Sport and the Hebrew Neglect of the Athletic Experience.”

It’s Just Not In Our Culture

If one examines cinematographic depictions of Jewish athletes, they tend to conjure up images of skinny, bespeckled individuals; Woody Allen wielding a tennis racket being a case in point.

Historically, it simply was not in the Jewish mindset to engage in athleticism. In fact, it ran counter to the Jewish emphasis on improving the mind. Similar to wealthy women who prided themselves on their soft hands, indicating a life of comfort, Jewish scholars emphasized their slight frames and commitment to (indoor) study (Ha’aretz).

Competitive sports was also contrary to a Jewish way of life as the Greeks used physical activities as a means for honoring their deities. Those who joined were thus viewed as “rejecting their religious and ethnic origins…in order to assimilate into the Greco-Roman world” (Ha’aretz).

As Jewish sports scholar, Jeffrey Gurock, reflects, “Judaism has never honored the athlete as its quintessential man or women” (Ha’aretz)

Things Changed With Zionism…or Did It?

Chalutzim or immigrants who came to pre-state Israel, recognized the need to invest in building strong bodies - not just minds - in order for Eretz Israel to become a reality. One would thus assume that “the Zionist desire to create a 'muscular' and robust Jewish representation should have embraced the athletic into its national culture,” observed Idels.

In fact, however, “the athletic body was mostly perceived as a vain and useless counterpart to such alternate ideal figures as the soldier or the pioneer.”

So Why this Apathy Towards Sports?

In Israel, athletic ventures were considered to be merely pastimes, not serious professions. When immigrants arrived from the sports-focused Soviet Union, they found little reception.

Idels described how athlete Nickolaus Hirschl joined the Hakoach Vienna wrestling team, but as he could not support himself through sports, he had to continue his family heritage as a butcher.

Change on the Horizon

A counter-trend emerged with the move towards the ‘New Israeli’, strong in both mind and body.

Author Max Nordau, business partner to Theodore Herzl (the father of modern Zionism), was seen as the founder of the Jewish athletic movement, coining the term “muscular Judaism” at the 1898 Second Zionist Congress (My Jewish Learning) and inspiring Jewish sporting clubs across Europe. Beyond “strengthening European Jews’ collective identity as a minority, [it also offered] a means of integrating into mainstream society” (My Jewish Learning).

So You Can Throw a Ball; Nu?

Sports clubs, such as Bar-Kochba and Hakoach Vienna started to gain repute, yet were not viewed with much enthusiasm; as Hakoach Vienna’s players did not speak Hebrew, many felt they could not truly represent Israel.

“Our national victory must be only realized by the old and proven way; with the book and with the plow”, stated Hebrew author Moshe Smilansky in 1924, scorning “youngsters who know how to kick a ball” (Idels). He continued, “football will not give us redemption…the only thing it has given us is imitation. Imitation without grace or honor” (Idels).

Joining the Movement

The interwar years saw a boom in the number of countries investing in the fledgling Olympics. “Modern sports rose to prominence as a global phenomenon, becoming, in many cultures, a representation of hegemonic national pride and a 'strong,' 'healthy' bodily image,” noted Idels.

And Jewish athletes wanted to be part of this exciting movement.

Ha’aretz (1924) dubbed the Hakoach Vienna football team as “the best example of masculine Judaism” that could usher in a ‘new era’ in sports (Idels).

In American circles, it was believed that athleticism could assist in combating anti-Semitism and gain acceptance into the larger society, as Judaism slowly changed from a religious identity to an ethno-cultural one (Jewish History and the Ideology of Modern Sport). “Elite athletes [were viewed] as representations of an integrated American Jewish Identity” (Redefining Jewish Athleticism).

From that point on, there was no stopping athletes from pursuing their passions and making their mark.

Hatikvah at the Olympics

“The heart is full of joy to see our flag…magnificently waving beside the [others],” noted reporter Lipa Levitan at the 1934 Women’s World Games in London. “It is a real Babel of languages here, our’s is heard here as well” (Idels).

Israel has been at every Summer Olympics since 1952, with the exception of 1980 held in Moscow in support of the American boycott, and every Winter one since 1994.

In the recent 2020 Tokyo Games, Israel sent its largest delegation yet (90), nearly double that of 2016 (Israel and the Olympic Games). This year proved to be a real milestone, with Israeli athletes leaving with more medals than in the last three Olympics combined, setting a number of records and reaching more finals competitions than ever before (The Times of Israel).

Shlomo the Scholar Alongside Aaron the Athlete

The Israeli sports arena has evolved dramatically. From being perceived as an affront to study, Israeli athletes have demonstrated that sports pursuits can be compatible with a modern Jewish identity, breaking records on the international arena.

One only has to look at Haredi American-Israeli marathon runner ‘Speedy Beatie’ Bracha Deutsch, or the 2018 documentary, “Heading Home: The Tale of Team Israel”, to see that Israeli athletes are here to stay.

(For an engaging overview of the world of Jewish athletes, check out the Canadian Jewish News’ Mentshwarmers.)