Research on exploding grapes catches fire in media outlets around the world

Cut a grape in half, throw it in a microwave and let the sparks fly.

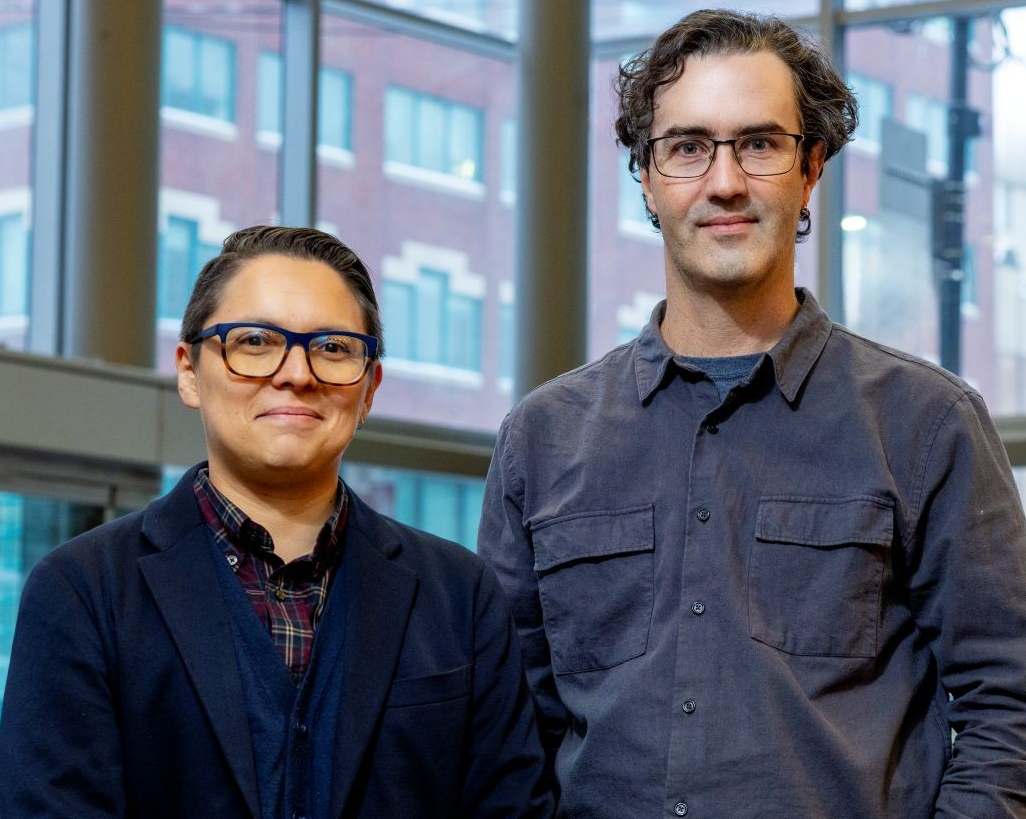

Visions of the bite-sized fruit catching fire ignited all over the internet last week thanks to the research work of Pablo Bianucci, associate professor in the Department of Physics, Aaron Slepkov, associate professor at Trent University, and Hamza Khattak, a master’s student at McMaster University.

The small research team published its findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and drew international coverage from international media outlets, including Wired, MSN, PBS and CBC.

We now better understand why this happens

How does it feel to have your research go viral?

Pablo Bianucci: It's been quite interesting — and intense! I did not expect such a degree of media interest. Aaron Slepkov was away with very limited internet access, so I’ve had to do many interviews.

Video of plasma created by irradiation of grape hemispheres in a commercial microwave oven.

Can you provide some background information on this line of research? How did it capture your attention?

PB: Aaron deserves a lot of the credit for publishing these findings. He started this project in 2013 with an undergraduate student, and then he kept doing experiments until he had a significant number of observations.

After Aaron saw me give a talk at a conference in 2015, he approached me because he wanted to involve somebody with photonics simulations expertise. When he told me about the project, I instantly wanted to get involved. This was the first time I heard about the grapes in microwaves experiment.

Video of plasma created by irradiation in a commercial microwave oven of hydrogel beads forming a dimer on a watch glass. The beads were first hydrated in de-ionized water and then soaked in a weak NaCl brine for one minute before filming.

What does this research mean for people who are unfamiliar with this work?

PB: While ‘kitchen science’ is cool and seems like flash with no substance, it can still lead to serious scientific results.

The most immediate impact is that we now better understand why this phenomenon happens. We also know that you don't need grapes to recreate this experiment — anything watery of a similar size should work.

We like to use grapes because the microwaves can focus on a spot that is much smaller than their wavelength. If we could find the right material — that behaves for light as water does for microwaves — we hope to do the same thing for visible light that could lead to very precise lithography.

High-speed video of grape dimer and hydrogel dimer irradiated in a commercial microwave oven, both igniting plasma and undergoing mechanical oscillations.

What are the next steps in this field of research?

Physical interpretations and modelling only consider a static system. There is some work in progress that considers what happens when we try to heat water and the ‘bouncing’ effect that we often observe.

Read “Linking plasma formation in grapes to microwave resonances of aqueous dimers,” published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Find out more about Concordia’s Department of Physics.