Pioneers, leaders and visionaries

October is Women's History Month, March 8 is International Women's Day.

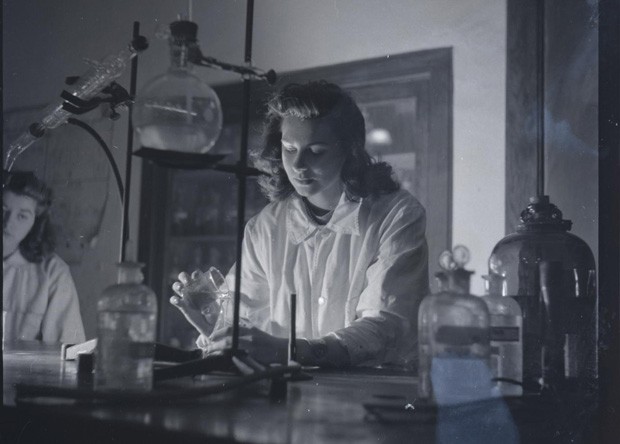

A student at Sir George Williams in the early 1940s. | Photos courtesy of the Records Management and Archives Department

A student at Sir George Williams in the early 1940s. | Photos courtesy of the Records Management and Archives Department

In 1959, Montreal native Katherine Waters became the first woman to teach at Loyola College, the Jesuit institution that merged with Sir George Williams University in 1974 to become Concordia.

The retired English professor recalls a visit to the college dining room to borrow some china coffee cups. “In I went, and some Jesuits who were also having their ‘elevenses’ stood up in absolute horror,” she says, laughing, in an interview recorded for Concordia’s Records Management and Archives.

“They said, ‘You can’t come in here! This is a cloistered place forbidden to women!’ So I said, ‘Oh excuse me, excuse me! I’m leaving ... I’ll just get the cups first.’”

In the past half-century, Concordia and its founding institutions have come a long way since those early days of cloistered dining rooms.

A gateway to social mobility

In the early 1960s, Loyola was playing catch-up, but Sir George Williams had been co-educational since 1926.

“It was very tied to the community, offering evening courses so people could advance themselves,” says Concordia Archivist Emerita Nancy Marrelli. “And in terms of faculty, there were women at Sir George from the beginning.”

The first woman to graduate was Rita Shane, who earned her BA in 1937. She went on to acquire a medical degree at McGill University.

“Sir George Williams was a gateway for my mother to become educated and attain social mobility at a time when other doors were closed to her,” her son Michael Katz said when she passed away in 2012.

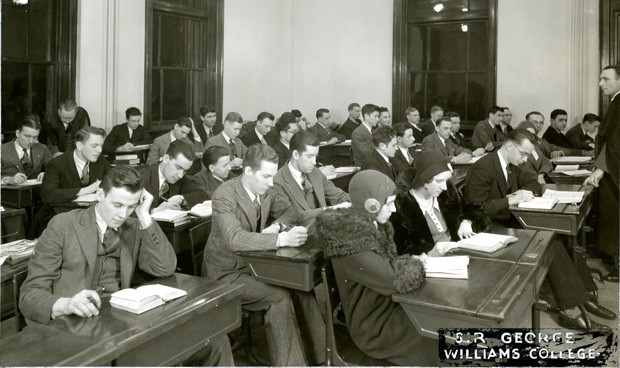

An early photo of a Sir George Williams College class at the YMCA building on Drummond Street.

An early photo of a Sir George Williams College class at the YMCA building on Drummond Street.

It wasn’t until 1959, the year Katherine Waters was hired, that Loyola admitted its first two female students. Loretta Mahoney and Gabrielle Paul would both go on to graduate from the Department of Engineering.

Many others soon followed, including Agatha Coolen, who graduated from the Bachelor of Commerce program in 1964.

“When I arrived at the college, there were no facilities for women,” she told the Loyola Alumnus newsletter in 1975. “But we were well treated by both professors and students.”

Some professors had a harder time adapting to the new reality. Marie Boyle, an education student who graduated in 1964, recalled a prof telling her that she belonged at home. “He claimed that I was taking a man’s place at the college.”

But by 1966, there were 568 women studying at Loyola. Twin sisters Christine and Virginia Gudas earned the highest mark (86.2) in the college’s final graduating class of 1974.

Nancy Marrelli earned a diploma from the Sir George Williams Business School in 1965, and went on to join the institution as a library assistant. She says that during the 1960s, second-wave feminism encouraged women to demand equal rights at the university.

“There was a recognition that there were inequalities, and certainly there was progress. Was there enough progress? No!”

Men continued to hold a more than equal share of faculty and senior administration positions, but women were playing an increasingly assertive role — in particular when it came to demanding fair labour conditions.

Katherine Waters, the first woman to teach at Loyola College, surrounded by her male colleagues in 1963.

Katherine Waters, the first woman to teach at Loyola College, surrounded by her male colleagues in 1963.

Waters served on both the Senate and the Board of Governors, and Marrelli was involved in the unionization of the library workers. In 1970, they formed the first white-collar union at Sir George Williams.

“If that unionization had happened 10 years earlier, it would have all been men,” Marrelli says. “The women were very active, and very involved, and very determined, through strikes, accreditation and all the rest of it.”

The rise of women’s studies

In the early 1970s, before the merger, female professors at both institutions began distinguishing themselves as pioneers in the field of women’s studies.

Marguerite Andersen offered an interdisciplinary course through the Département d’études françaises at Loyola. Greta Hofmann Nemiroff and Christine Allen (who later became Sister Prudence Allen) taught the Nature of Woman course in Sir George Williams’s Department of Philosophy.

“Women were very isolated, even intellectually,” Nemiroff told Concordia’s Thursday Report in 1998. “We gave them the opportunity to write about their own experiences.”

Other pioneers soon followed, including French professor Maïr Verthuy, who gave the first-ever university course on female Quebec writers.

“I spent a lot of time introducing women into courses like the History of French Literature — making sure women had their place in there,” Verthuy recalls.

In 1978, four years after Concordia’s formation, a group of professors joined together to create the Simone de Beauvoir Institute. Verthuy was appointed its first president.

Named after the famous French author and philosopher, the institute studies feminism and questions of social justice. This year, it celebrates its 35th anniversary.

“I want my work to speak for itself”

In the past 40 years, dozens of staff and faculty positions, associations, organizations and student groups were formed to promote the status of women at Concordia and in the world at large.

Elizabeth Morey retired from her position as dean of students in 2011. During the mid-1980s, she served as advisor to the rector on the status of women. Part of her job involved dealing with individuals who exhibited sexist behaviour.

“One professor had a slideshow in his class, and every fifth or sixth slide was of naked women,” she says. “It was a matter of trying to educate him about how inappropriate that was!”

Morey says the university proved that it was willing to address gender issues.

“I think Concordia can be proud in some ways of its track record, and of its institutions like the Simone de Beauvoir, as well as the fact that it’s opening a sexual assault resource centre.”

A report issued in November 1982 by Concordia’s Committee on the Status of Women showed that only 16.9 per cent of full-time faculty were women. The latest figures show that number has climbed to 38 per cent, and 50.5 per cent of all permanent employees are women.

Archivist Emerita Nancy Marrelli: “There was a recognition that there were inequalities. And certainly there was progress.”

Archivist Emerita Nancy Marrelli: “There was a recognition that there were inequalities. And certainly there was progress.”

“Change is slow,” Marrelli says. “But things certainly have changed. When I came in, virtually everybody in authority was a man. The idea of a woman dean was just unthinkable.”

Paula Wood-Adams was appointed dean of Graduate Studies earlier this year. She joined Concordia in 2001 as an assistant professor in mechanical engineering, and was the graduate program director of the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering from 2006 to 2012.

Wood-Adams remembers when her chosen field, and the conferences she attended, were filled almost exclusively with men. “Now it’s completely different,” she says. “It’s not half and half, but it’s maybe 30 per cent, and I see a lot of young women students. It’s nice to see that evolution.”

Journalism is another area that was male-dominated. Now, roughly two thirds of the undergraduates in Concordia's Department of Journalism are women.

“I think it’s changing pretty rapidly,” says Salima Punjani, a student in the graduate diploma class.

Punjani insists that the last thing she seeks is special treatment. “I want my work to speak for itself.”

Fifty-five years earlier, in 1959, future engineering graduate Loretta Mahoney told the Loyola News: “I’d rather be known as a good student, than as the ‘girl’ at Loyola.”

Updated March 5, 2014.