Concordia PhD candidate researches how young bilinguals learn French and English simultaneously

In much of Montreal, it’s common to overhear conversations between people who switch effortlessly between French and English. More than half the city’s residents are bilingual and, for many, this dates back to childhood.

But how do babies and toddlers learn multiple languages at once? And does doing so affect their development and communication skills overall?

Lena Kremin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Psychology. Her work at the Concordia Infant Research Lab focuses on language acquisition in bilingual children, and specifically how infants learn to separate their languages.

Kremin says that, contrary to what many parents fear, raising a child in an environment where multiple languages are spoken does not confuse or impede their learning.

‘There are a lot of myths about raising a child bilingually’

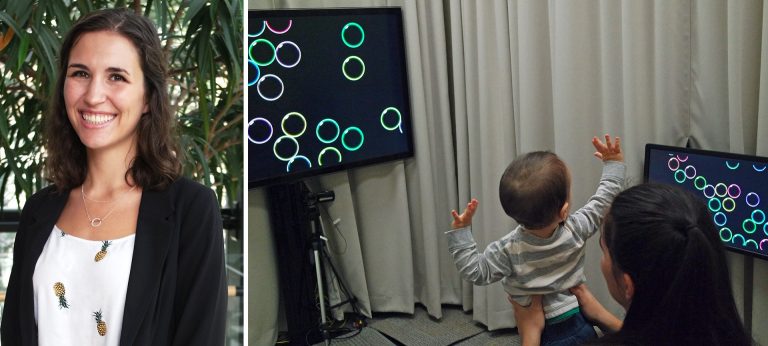

How does this specific image (top right) relate to your research at Concordia?

Lena Kremin: This image shows a participant about to begin a study in the Concordia Infant Research Lab. We use this setup to measure a baby’s interest in different speech sounds. During a study, the baby will sit on their caregiver’s lap as we play different sounds out of speakers on opposite sides of the room.

At the same time, we have a spinning pinwheel on a TV screen right above the speaker to give the baby something to look at. We use the amount of time the baby looks at the pinwheel as an indication of how interested they are in the sound that’s playing over the speaker.

I’m currently using this method to examine how bilinguals learn whether a new word is French or English.

What is the hoped-for result of your project?

LK: My project is attempting to teach bilingual toddlers, ages one to three, a new, made-up French word and a new, made-up English word by using it in combination with words they already know like “cat” and “chien.”

If the toddler learns that the new word belongs to one of their languages, I think they’ll be surprised when they hear it with a word from the other language, just like how adults may be surprised when they hear “le dog” or “the chat” instead of “the dog” or “le chat.”

The results from this project will provide insights into how bilinguals learn two separate languages.

What impact could you see it having on people’s lives?

LK: There are a lot of myths and concerns about raising a child bilingually. Many parents worry that if they speak two languages to their child, they might get confused and not learn them properly.

Research has shown that this is not the case, but my project would be the first to investigate whether children can use what they already know to classify which language a new word belongs to.

What are some of the major challenges you face in your research?

LK: Babies are hard to study because they don’t follow instructions and may even start crying when they don’t like the task. This means that I have to be a bit creative when I’m designing a study. I generally rely on tasks that do not require instructions and instead focus on measures of a baby’s behaviour, like what objects they look at on a screen or how long they listen to a particular recording.

Another challenge that I face is in recruiting. To find participants for the studies in the Concordia Infant Research Lab, families may be recruited through community programs or sent a letter to see if they are willing to bring their child to our research lab. It often takes close to a year to find enough families to participate in one study.

Fortunately, the lab has ties with the community and wonderful research assistants who help with this step in the process. If you or someone you know is interested in participating, please visit the lab’s website to sign up!

What first inspired you to study this subject?

LK: When I was younger, I went on a family vacation to Spain and was amazed — and a little jealous — at how easily the children there spoke Spanish. That experience sparked my curiosity, and I became interested by how children learn to speak a language so quickly and seemingly effortlessly.

Combining this with my personal love of learning and speaking multiple languages, I began wondering how bilingual children learn both of their languages at the same time. I’ve been fascinated by the process of language learning, particularly by bilingual children, ever since.

What advice would you give interested students to get involved in this line of research?

LK: I would first advise students to take a course in developmental psychology. There are so many fascinating topics covering how humans learn, change and grow throughout their lifetimes that it can be overwhelming to choose one to focus on. Taking a class that covers a wide range of development can help a student find what interests them the most.

My next piece of advice would be to volunteer in a research lab. For me, hands-on experience as an undergrad was incredibly important, since it showed me what research in this field was really like.

What do you like best about being at Concordia?

LK: There are so many opportunities to get involved in interesting research. Organizations such as Concordia’s Centre for Research in Human Development and the Bilingualism Interest Group have connected me with scholars from other labs at Concordia and across Montreal. This has allowed me to learn about many different methodologies and ideas that I can use in my own work.

Are there any partners, agencies or other funding/support attached to your research?

LK: My research is supported by fellowships from the Fonds de recherche du Québec (FRQ) and the Centre for Research on Brain, Language and Music.

My work is also a beneficiary of grants to my supervisor, Krista Byers-Heinlein, from the Natural Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Concordia University Research Chairs program.

Find out more about the Concordia Infant Research Lab.