For many, the word yoga evokes images of spandex pants and bendy bodies. Yet yoga as a route to physical fitness is largely a product of the 20th century, diverging significantly from its ancient Indian roots. “The word yoga itself might best be translated as ‘discipline,’” says Shaman Hatley, associate professor in the Department of Religion, who teaches courses on the history and philosophy of yoga.

When the idea of yoga first came about — which records show was more than 2,000 years ago — it meant disciplining the mind through self-mastery techniques, primarily meditation.

“In the belief system of classical yoga, there is a fundamental duality between the spirit or core of one’s being and the material world, including one’s body-mind complex,” Hatley explains. “Yoga meant the discipline of isolating the spirit from matter, mainly through meditation, and achieving perfect tranquility and absolute peace.”

Nearly 2,000 years ago, the Indian sage Patanjali defined yoga as the cessation of the fluctuations of thought. A foundational yoga text, his Yoga Sutras are still commonly taught in yoga teacher-training programs today. While Patanjali refers to disciplining the mind, yoga has come to encompass a wide range of bodily disciplines.

“What we call yoga today, centred on physical postures, dates back to the 12th- to 13th-century tradition of hatha yoga. Before that time, the postures spoken of in yoga texts were almost exclusively sitting postures for performing meditation,” says Hatley.

In contrast to modern yoga, asceticism or self-denial had been a necessary component from ancient times. “There’s a pronounced aim in the yoga tradition to conquer desire, to conquer the need to experience bodily comfort and pleasure, to overcome all kinds of limitations.”

Attaining mastery over mind and body held metaphysical benefits, enabling the practitioner to distill spirit — one’s true, divine self — from the lesser material world, uniting the spirit or soul and god.

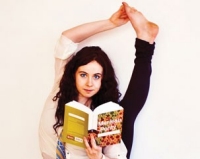

Yasmin Fudakowska-Gow, BA 04, owner, director, teacher at Yasmin Yoga Loft

Yasmin Fudakowska-Gow, BA 04, owner, director, teacher at Yasmin Yoga Loft

Shaman Hatley

Shaman Hatley

Harold Simpkins

Harold Simpkins

Simon Bacon

Simon Bacon

Vanessa Salvatore

Vanessa Salvatore

Dawn Mauricio, BComm 05, senior teacher at Naada Yoga

Dawn Mauricio, BComm 05, senior teacher at Naada Yoga

Lois Baron

Lois Baron

Nicole Crouch

Nicole Crouch

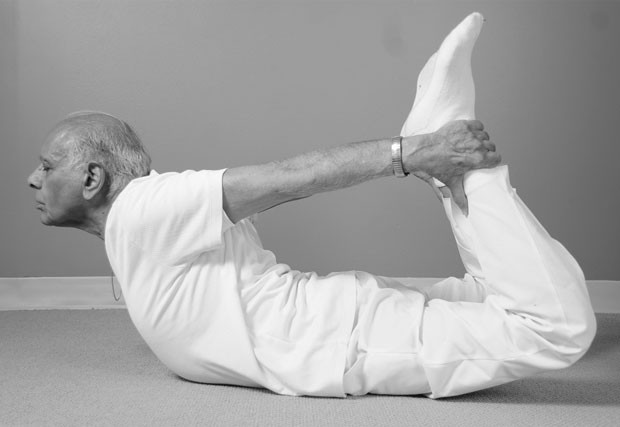

Madan Bali, BA 80, founding director at Yoga Bliss

Madan Bali, BA 80, founding director at Yoga Bliss

Lauren Bird

Lauren Bird

Jennifer Maagendans, BA 00, owner, director and teacher at Luna Yoga, with husband Jason Kent, BFA 01

Jennifer Maagendans, BA 00, owner, director and teacher at Luna Yoga, with husband Jason Kent, BFA 01