The social life of the senses

The study of the senses used to be the preserve of psychology. Now, scholars from across the arts, humanities and social sciences are focusing on the senses as both objects of study and a means of inquiry.

These investigators go on sound walks, cook up dishes from the past, create olfactory works of art and generally delve into the many fascinating ways in which people have used their senses throughout history and across cultures.

David Howes calls this “the sensorial revolution.” Howes — a professor of anthropology in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, and director of Concordia’s Centre for Sensory Studies — recently published Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society (Routledge), a book co-written with cultural historian Constance Classen of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music, Media and Technology at McGill University.

Howes and Classen first teamed up in 1994 to write Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell (Routledge) together with Anthony Synnott, a professor of sociology in Concordia’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Aroma’s interdisciplinary approach to the study of olfaction made it a landmark work in the field of sensory studies.

Ways of Sensing explores the history of the senses in six different disciplines: art, medicine, law, politics, marketing and psychology.

Howes and Classen uncover how the senses were banished from the diagnosis and treatment of disease in modern hospitals, a development they contrast with their extensive use in the aromas, massages and musical elements found in alternative and traditional medicines. What, they ask, is modern medicine missing by ignoring the possibilities of sensual healing?

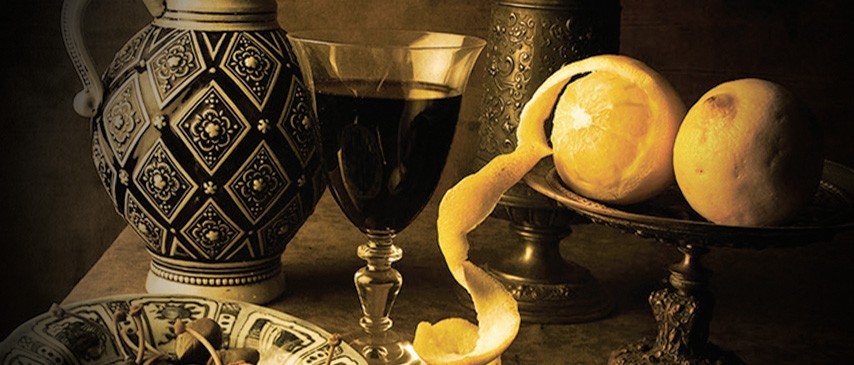

They likewise show how the senses were barred from the museum, and illustrate how current artistic and educational trends are turning once sterile galleries into vibrant sensory gymnasia. According to the authors, “the definition of art is no longer confined to that which meets the eye.”

There has been a sensory explosion in the marketplace as well. Marketers are competing to brand our senses with trademark sounds, scents and colours, giving them names like “Cadbury purple.”

According to Howes, “This privatization of sensations is of deep concern to some, who see the sensory commons as undergoing increasingly rapid depletion.”

In chapters focusing on politics and law, the authors highlight other important ways in which the senses shape society, from the common “sensotyping” of immigrant groups as “smelly” to the argument that the ringing of church bells should be deemed “noise pollution” and outlawed.

“Concordia researchers are in the vanguard of the sensorial revolution,” Howes says.

In addition to the Centre for Sensory Studies, which counts a dozen faculty members and over two dozen graduate students among its ranks, Concordia is home to labXmodal a studio lab founded by Chris Salter, an associate professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts. Salter’s recent works include “Atmosphere,” “Displace” and other pieces he calls “total sensory environments.”

The university also houses the Sense Lab, an initiative dedicated to exploring research and creation founded by Erin Manning, an associate professor in the Department of Studio Arts and Film Studies and the Concordia University Research Chair in Relational Art and Philosophy.

This term, Concordia hosted a talk by renowned Norwegian smell artist Sissel Tolaas, who discussed how she amassed a collection of more than 7,000 odour compounds, which she uses to create olfactory art. The talk, sponsored by Hexagram CIAM, was followed by a discussion about the senses moderated by Howes.

These diverse initiatives illustrate the central theme of Ways of Sensing: that sounds, sights, smells, tastes and touches are the stuff of culture — and of cultural researchers.

Learn more about Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society.