A joint study sheds new light on some long-held myths about the baby boom

Public health initiatives launched in the 1910s laid the foundation for the baby boom generation, according to a new joint study by researchers at Concordia University and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS).

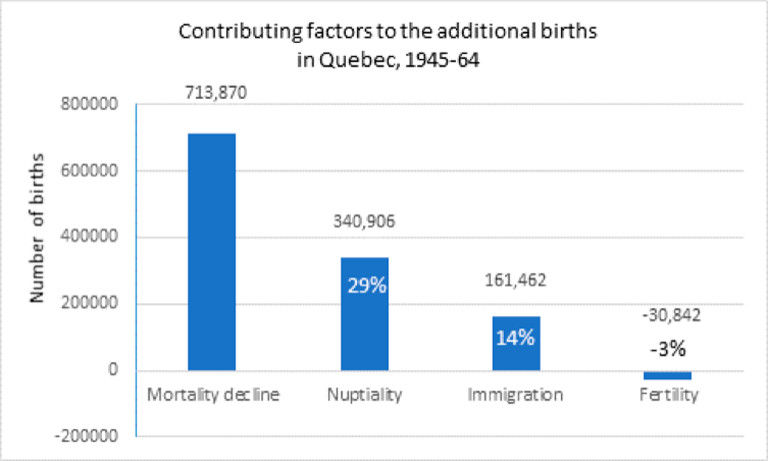

Without improvements to sanitary conditions 30 years prior, researchers estimate that 60 per cent of births between 1945 and 1964, representing more than 700,000 Quebecers, would never have occurred.

The surprising findings debunk the most common myths about the baby boom.

“Contrary to popular belief, the number of children per married woman actually decreased,” explains INRS professor Benoît Laplante.

Published last November in Population Studies, the paper, co-authored by Concordia professor Danielle Gauvreau, shows that compared to the previous generation, the women who would go on to be the mothers of baby boomers were much more likely to survive to adulthood and get married. The authors argue that reduced mortality rates — paired with increased marriage rates — account for 89 per cent of the 1.2 million additional births in Quebec following the Second World War.

“Without these two linked phenomena, there would not really have been a baby boom,” explains Gauvreau, who is also the chair of Concordia's Department of Sociology and Anthropology.

Improved public health: a game changer

The reduction in infant and child mortality beginning in the 1910s paved the way for the upcoming baby boom.

At the time, Quebec did not have systematic data on its population dynamics. It was only in 1926 that the province officially compiled vital statistics such as births, deaths and marriages. As Laplante explains, these statistics were a shock to authorities.

“They saw that children were dropping like flies. This information woke people up, and that’s when new public health policies were introduced, reducing infant mortality rates long before the advent of antibiotics,” he says.

The construction of sewers, as well as the widespread introduction of vaccinations, sanitary measures and improved nutrition, played a central role. Infant mortality fell from 127 deaths per 1,000 in 1926 to 83 per 1,000 in 1936, and continued to improve in the subsequent years.

As a result of these measures, a greater number of women survived childhood and married in large numbers after the war.

A demographic microsimulation method developed by demographer and INRS professor Alain Bélanger was used to calculate exactly how these phenomena contributed to the baby boom. The Quebec Inter-University Centre for Social Statistics provided some of the data for research purposes.

This innovative method allowed researchers to assess the impact of different scenarios on the number of births during the baby boom.

Another important driver of the boom was the favourable economic context, which made it easier for couples to tie the knot, along with a decreased interest in religious vocations. In short, more people were getting married, and at a younger age.

“We were giving the increased marriage rate most of the credit for Quebec’s baby boom, but married women were having fewer children on average, so this wasn’t a sufficient reason,” says Gauvreau.

The study shows that immigration was also a major contributor to the size of the post-war generation, accounting for 14 per cent of births.

Lower fertility accounted for a 3 per cent reduction in birth rates, meaning the baby boom was ultimately a matter of there being more families rather than larger ones.

The researchers hope this method can be applied in other countries that have experienced baby booms to highlight the varied causes across different societies.

The study, The Mechanics of the Baby Boom: Unveiling the Role of the Epidemiologic Transition, is co-authored by Gauvreau and Laplante, as well as Patrick Sabourin and Samuel Vézina, doctoral candidates at INRS. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) provided the financial support.

Read the full study: The Mechanics of the Baby Boom: Unveiling the Role of the Epidemiologic Transition

Find out more about Concordia's Department of Sociology and Anthropology.