Photographs show us what once presented itself before a camera, but all further meaning is attributed by a willing (or unwilling) beholder. There is the time of exposure but there are also many other ‘times’ involved in the ‘meaning-making’ of a photograph. Like memories, photographs are more than the original moment captured – they are the culmination of several moments, intentions and associations. It is only by evolving and adapting within the ever-changing present, that they remain dynamic and relevant.

My current research represents an adaptation within my present – a continuation of my lifelong preoccupation with the rich and fascinating space between photographic media, body and image.

I’ve never been sure where this pursuit would lead next. I'm just chasing ghosts.

Introduction to Magic

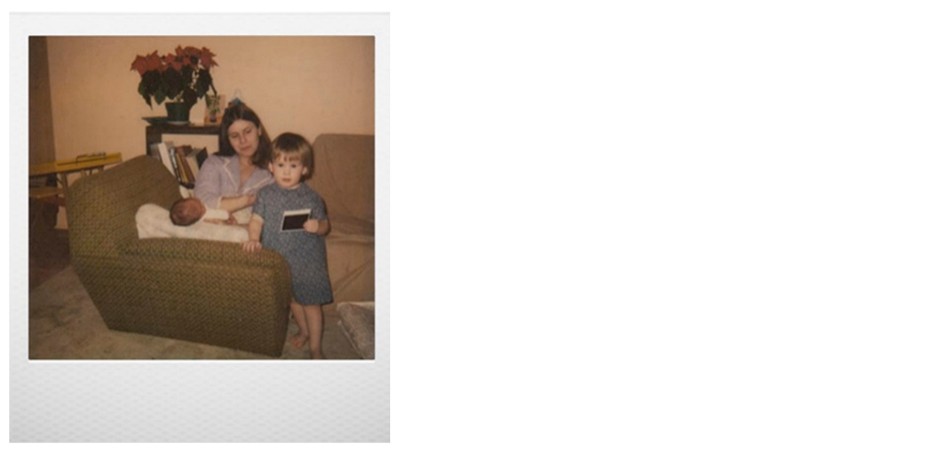

There’s a Polaroid from my childhood – rediscovered a decade ago – that has come to dominate my memory of these earliest years. This is especially strange as none of the individuals in the photograph remembers the moment pictured. The one person who might have, is the photographer – thought to be my grandmother Audrey Hamer – gone from us nearly two decades now.

In the photograph, nearly-two-year-old me, stands next to my mother and newborn sister – holding yet another Polaroid. I believe this is the first time I ever saw an image appear and I believe this apparition is of the person who is seated before me. Is it my grandmother? Am I looking over towards her, wondering how she could be in my hand and yet also there across from me? It doesn’t matter. This is my memory; it resonates with who I am now. And I love it.

The impact of this pre-memory moment has stayed with me. By the time I was eight years old, my mother had relinquished ownership of her camera and for several years I could be found behind this magical box. My fascination with photography has not dissipated.

Away at summer camp, my mother would equip me with two or three rolls of precious film to load in my Kodak Instamatic that I would carry with me everywhere in a yellow and blue camera bag. I remember the smell of the film as I opened the plastic. Pure potential. Magic.

I would spend a lot of time looking for interesting things to shoot. Singing off into space and arresting things before me. How could this little box capture light? How lucky was I to keep these clouds forever? I collected moments – little treasures that would be revealed upon my return home. I was a weird kid.

Me and some of my ghosts, October 2021. Credit:

Me and some of my ghosts, October 2021. Credit:  Views of Camp Amy Molson. Credit: F. Hamer, (about 8 years old)

Views of Camp Amy Molson. Credit: F. Hamer, (about 8 years old)

Dave, don't come home for a bit. I'm haunting the apartment. Credit: F. Hamer, (about 20 years old, BFA Major in Photography Concordia University)

Dave, don't come home for a bit. I'm haunting the apartment. Credit: F. Hamer, (about 20 years old, BFA Major in Photography Concordia University)

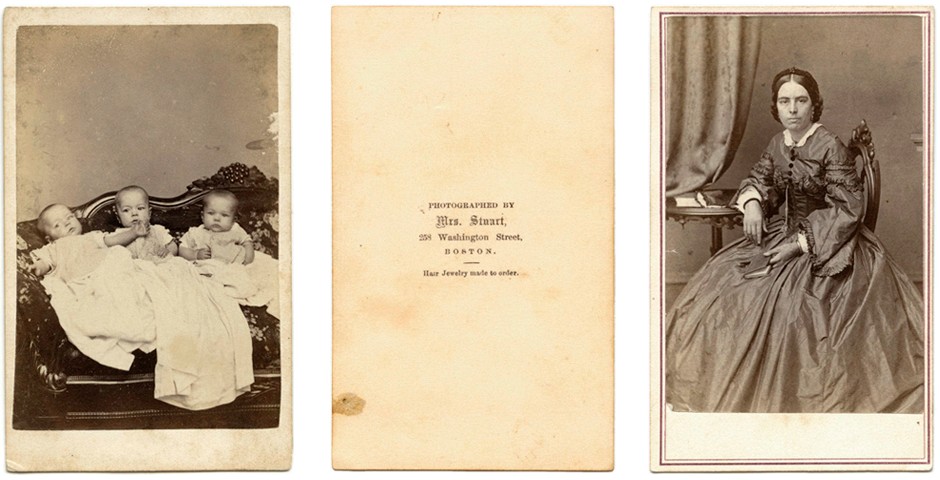

Cartes-de visite by Helen F. Stuart, The Chase Triplets? (Thurston S., Lucy Hale, and Alice March, born July 2, 1861) & Portrait of Unidentified Woman, 1861–67. Credit: Hamer private collection.

Cartes-de visite by Helen F. Stuart, The Chase Triplets? (Thurston S., Lucy Hale, and Alice March, born July 2, 1861) & Portrait of Unidentified Woman, 1861–67. Credit: Hamer private collection.

Mom, baby Tiffany and I. Credit: Photo (likely) by Audrey Longworth Hamer.

Mom, baby Tiffany and I. Credit: Photo (likely) by Audrey Longworth Hamer.