Sylvie Ouellette is a doctoral candidate in Chemistry/Biochemistry. She received her Bachelor’s in Journalism from Concordia in 1995. In 2017, Sylvie obtained a BSc (Honors) in Cell and Molecular Biology and then joined the Pawelek lab. Sylvie investigates how bacteria scavenge essential iron from their surroundings. Her findings could pave the way for new classes of drugs to contribute to the fight against antibiotic resistance.

Credit: Creative Commons

Credit: Creative Commons

If you could take a handful of soil from any garden, forest or riverbed and observe it under a microscope, you would see that it is teeming with life. Even a sample small enough to fit in a thimble includes an impressive community of microbes such as bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses. These micro-organisms live in precariously balanced proportions, either co-existing by symbiosis or keeping enemies at bay. Microbes communicate by secreting compounds that signal a threat or an opportunity to their kin. Others produce antibiotics that repel invaders. Each species serves a purpose.

That is the essence of an ecosystem – which can be found on the most basic scale such as soil, all the way to entire continents and indeed our planet. Trees capture sunlight and carbon dioxide to make sugars, the building blocks of their leaves and pulp. When decaying, this organic matter feeds micro-organisms in the soil, which then fix nitrogen from the air to be supplied through the root of the trees to help them grow. Micro-organisms also contribute to the erosion of sand and silt to free the minerals that plants need. On this much wider scale, here again each species serves a purpose.

Two-way Collaboration

Credit: Creative Commons

Credit: Creative Commons

Such ecosystems also live on your skin, no matter how clean you are. The same applies to your nose, throat, and the whole of our respiratory tract. Most of the microbes that have settled there are useful to you. This collaboration is called symbiosis, and in optimal conditions can be compared to a ‘’you scratch by back, I’ll scratch yours’’ kind of arrangement.

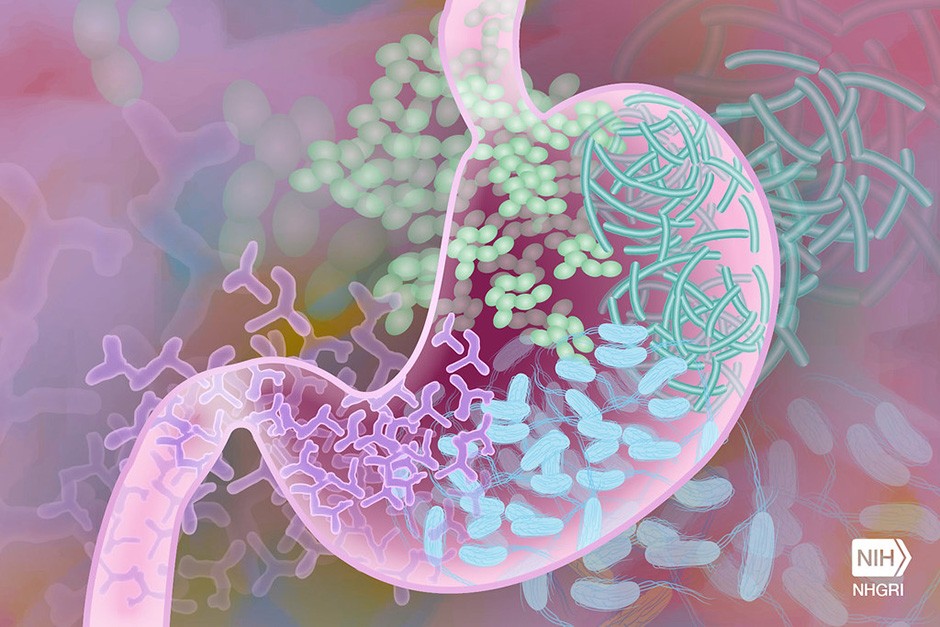

In recent years, a lot of research has been devoted to studying a lesser known, much more mysterious ecosystem: the one that lives in your gut. From mouth to anus, your entire digestive tract is lined with its own communities of microbes, which vary depending on the organ. Even your stomach, long thought to be sterile due to its low pH environment, is filled with bacteria such as lactobacilli, an acid-loving species that contributes to the breakdown of dairy products.

We have known for decades that the lower part of the digestive tract (small intestine, colon and rectum) was colonized by bacteria, yeast and even protozoa that helped with the final steps of decomposition of the food we eat. The simplistic view held that the community comprised micro-organisms whose function was solely for garbage disposal. But that view has long been disproven, especially as regards bacteria. The gut microbiota, as it is called, is now known to serve a very specific purpose. It is estimated that our intestines is home to over 1 kg of various micro-organisms. This represents trillions of cells, much more than make up your whole body. Indeed, there are more of ‘’them’’ than there are of ‘’you’’. Some micro-organisms are essential for you, some can be dangerous, and many more are neutral. More and more, research is uncovering evidence that this ecosystem has a direct effect on your health and well-being.

More Than Passengers

Credit: Creative Commons

Credit: Creative Commons

A significant proportion of what you eat is not digestible to you. This is especially the case for fibrous foods such as the stems and leaves of plant matter. However, the bacteria in your gut will degrade and feed on this. So, yes, you support them, but what do they do for you in return? Well, through degradation of what you feed them, bacteria synthesize essential compounds such as vitamin K and short chain fatty acids such as butyrate, as well as several vitamins of the B group. Other key players such as yeast and protozoa, although not directly beneficial to us, nevertheless take on a supporting role in making sure the bad, disease-causing germs are kept in check. Therefore, this army of good germs is your first line of defence against invading pathogens and are thus crucial to your health.

And this effect is seen well beyond the terrain itself: an overall balanced, properly fed gut microbiota will strive to maintain its environment in its best condition to aid in the absorption of other nutrients that you digest. All this at a modest price: all they require is whole, unprocessed fruits and vegetables.

Communication With Your Brain

Many end-products of bacterial digestion have also been identified as key players in the maintenance of the gut-brain connection. Again, through the assimilation of the foods you eat, bacteria can synthesize neurotransmitters, which will be shuttled to your brain and affect your emotional well-being, either in a good or a not-so-great fashion, depending of the type of bacteria. One example is gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA), which modulates fear and anxiety. And as mentioned before, a balanced, thriving microbiota keeps the gut healthy, which in turn optimizes its production of hormones like serotonin that controls your mood levels. Although this has only come to light in recent years, the term ‘’gut feeling’’ has been used for centuries and is now more appropriate than ever.

So What to Do?

Credit: Creative Commons

Credit: Creative Commons

Your body and your gut microbiota are engaged in a close, mutually beneficial collaboration. And just like any type of business arrangement, you can only reap rewards if you hold up your end of the bargain. Research points to whole foods as the preferred fuel for the good micro-organisms that impact us, as well as the more neutral ones that serve as guardians of this precarious equilibrium. Processed and junk food, on the other hand, may not only be detrimental to their function but might also favour the growth of more harmful species, sending the intestinal ecosystem off balance. Eating well has long been known to benefit our health, but now we know that the link is not as direct as was previously thought : feed your body properly, yes, but also think of the little critters in your gut.

Since they outnumber you, who’s really feeding whom?

About the author