With over 20 years of international experience working in the child welfare sector, Zeina Ismail-Allouche has contributed to international initiatives promoting family strengthening and participated in the drafting of UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care for Children. Zeina has co-written a book chapter on the challenges facing indigenous youth coming of age out of care in Canada. She has published many articles on the reform of the child welfare sector.

Blog post

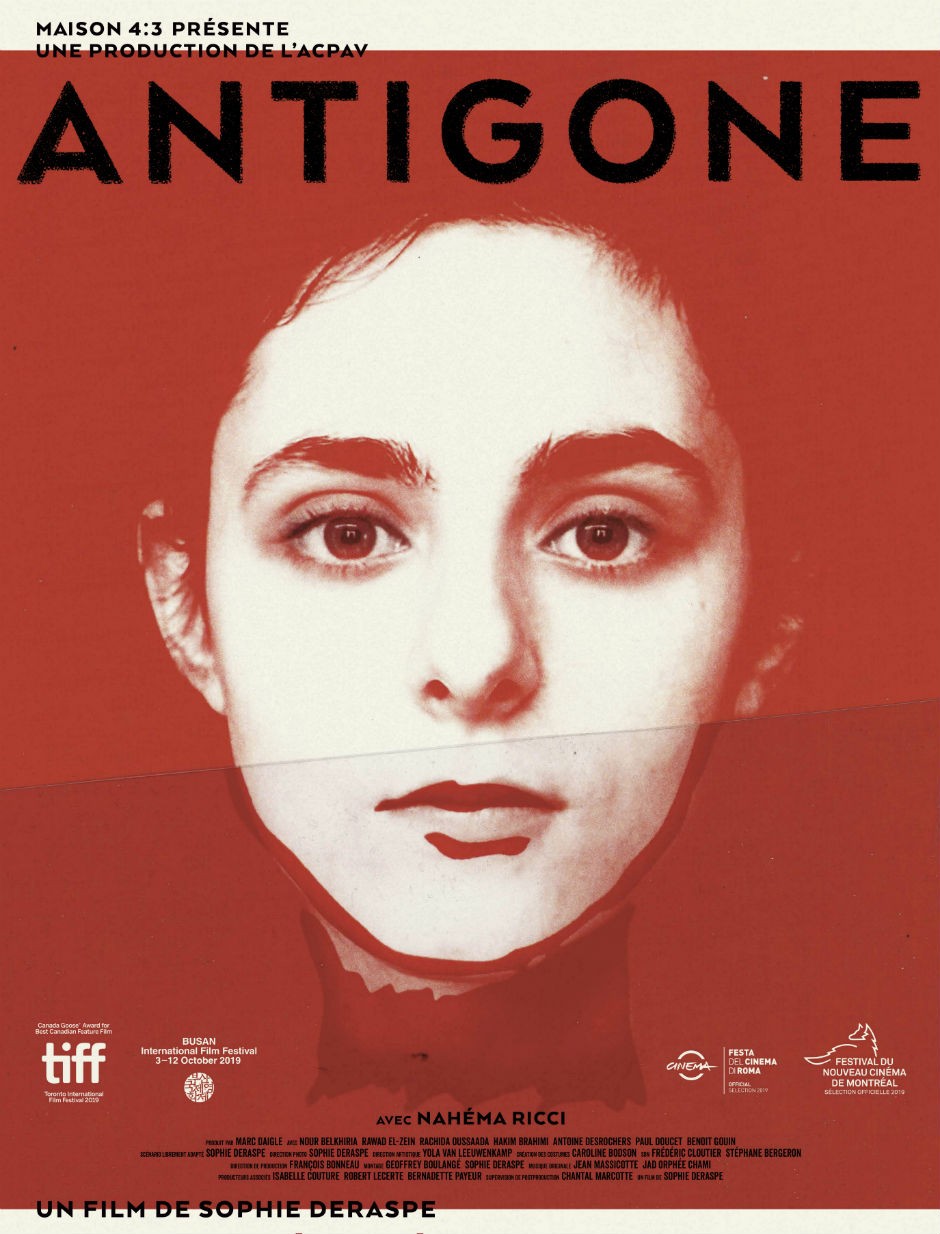

Antigone and the question of representation

Photo by Lou Scamble

Photo by Lou Scamble

A woman, on her own, facing the state and claiming back her right to be. This is what invited Sophie Deraspe to revisit Antigone — the ancient Greek play by Sophocles — through the eyes of the modern 17-year-old Antigone, performed by the talented Nahéma Ricci.

Antigone has arrived in Canada as a toddler with her grandmother, sister and two brothers following the assassination of her mother and father back home in Algeria. Antigone confronted the systemic violence and was ready to sacrifice her right to citizenship in order to save her brother from jail.

“Mon coeur me dit (my heart tells me),” she says.

Answering my questions in a coffee shop on a cold morning in Montreal, Sophie unfolded her connections to a movie that won last year’s prize for Best Canadian Feature at the Toronto International Film Festival — among many other prizes — and was Canada’s choice for the Oscars. Although Antigone didn’t make it on the shortlist, the movie keeps traveling all over the world and is being recognized as one of the best movies of 2019.

As a student, Sophie Deraspe took part in a community-based project to explore the value of Canadian citizenship by listening to the views of people who are in the process of getting it and those who already acquired it. Born in Quebec to a Canadian family, Antigone’s director explains that the first time she applied for a passport was to travel.

“I was sure that I would get it. I mean it is something taken for granted. We don’t even think of it! However, for some people, obtaining Canadian citizenship and a passport might become a question of life or death […] In that context, Antigone was my way to honour those life stories.”

The words of Sophie took me back to July 15, 2015. On that day, we landed in Canada as an immigrant family — Rabih, my husband; Jad, my 17-year-old son; Yasmine, my 13-year-old daughter; and myself. We left behind our home, families, friends, memories and the smell of the sea.

I remember the day when my husband and I decided that we needed to secure a better life for Jad and Yasmine away from fear, wars and continuous instability. It was indeed a tough pathway and it was not without cost.

Even though we, as a family, came from a certain privilege — the least of it is that we all mastered two languages — I couldn’t help but identify with Antigone’s grandmother facing the immigration agent upon arrival, as an immigrant, to Montreal’s airport. I can never forget the feeling of disarmament and dispossession under the contemplating eyes of my kids.

I can still see them watching my anxiety while standing on the frontline between the unknown of the immigration fantasy and the fear of authorities sending us back to a threatening reality. The reality is that immigration can never be only about winning; it is also about loss.

For me, Antigone was the first movie, conceived by a Quebecoise director, that confronts the romanticized immigration process and the promised heaven for refugees while subtly addressing systemic violence and the realities of the detention centres for youths. Like Antigone, Sophie Deraspe was bold to reveal the unsaid and to convey the unseen.

While watching the movie for the first time, I couldn’t silence my researcher’s voice that was raising questions about the director’s legitimacy to address the issue of immigration. From an ethical perspective, any attempt to account for the voices of the most marginalized is immersed with sensitivities around authority, voice and representation.

Agency becomes a fundamental concern, especially since Antigone comes at a time when representation has generated a public debate with the recent controversy around Indigenous representation in Kanata, created by Robert Lepage, in the absence of Indigenous artists.

Sophie Deraspe makes it clear that Antigone is not meant to speak on anybody’s behalf.

“I speak for myself, surrounded by other people of different backgrounds and realities. Those people inspire, participate, create with me.”

Sophie perceives herself “as a captain leading a boat to a foreseen but unknown territory.” It is that same sailing boat that embraced my son, Jad Chami, the immigrant back then, now a Canadian artist and a Concordia BFA alumni, to co-compose the original soundtrack of Antigone.

Describing her creation practice, Sophie says that a film transcends its author, its creators, its performers, sometimes even its destination.

“My films are a journey we undertake. A journey that might resonate with some lived realities. And in doing so, it has the power, sometimes, to change the world we live in, or at least some perceptions we have of it. It certainly has the power to move and shake as art does. But it never pretends to be the reality or the voice of a group of people other than the ones sailing on this specific boat.”

I left Sophie on that day wondering about the fine line between representation and art-creation. From a researcher’s perspective, the tension around representation is full of historically silencing minorities. Yet, here I am working on a PhD research-creation based on the life stories of individuals who experienced transracial/intercountry adoption, and I am not adopted. Despite my long years of activism and closeness to the subject matter, some might still perceive me as an outsider.

I think that this is perfectly legitimate. I will have to situate myself and explain my connections to the world of adoption at every encounter with people who have experienced adoption. Informed by Indigenous methodologies, l learned that authorship and agency should be put back in the hands of those who have been silenced. Like Sophie, I will be sailing on a boat, but would I really be the captain?

Antigone official poster, used with permission.

Antigone official poster, used with permission.

About the author