With over 20 years of international experience working in the child welfare sector, Zeina Ismail-Allouche has contributed to international initiatives promoting family strengthening and participated in the drafting of UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care for Children. Zeina has co-written a book chapter on the challenges facing indigenous youth coming of age out of care in Canada. She has published many articles on the reform of the child welfare sector.

Blog post

Beyond the consent form: how to ensure that our research is ethical?

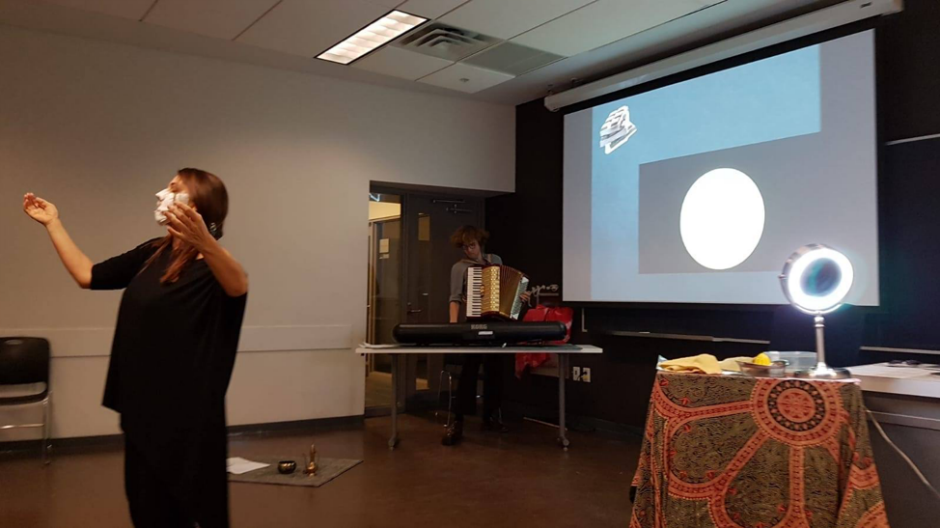

A Draft Story of Invisibility (2), performed as part of the Oral History Association conference organized in collaboration with COHDS, Concordia University, 2018.

A Draft Story of Invisibility (2), performed as part of the Oral History Association conference organized in collaboration with COHDS, Concordia University, 2018.

For many PhD candidates, submitting the ethics package for approval is a major milestone in the journey toward implementing a research project. Beyond getting the university’s green light to embark on the project, ethical considerations constitute a major component of my proposed research methodologies to undertake an oral history research-creation project based on the life stories of individuals who have experienced transracial and intercountry adoption.

Engaging with stories of separation from the mother and the longing to reconnect with origins is not a painless process. Telling one’s own story evokes tough remembering.

While developing my research methodology, I had many questions about my legitimacy to invite others to unfold their stories. In parallel, I was concerned with the impact of performing controversial matters to the public. The conversation on intercountry and transracial adoption is emotionally charged. Some approach it as a charity that saves the life of an orphaned child, while others consider it a colonial practice that rips the child from their origins.

What knowledge should I favour to understand my research question?

In my work developing my research proposal, I found in Indigenous methodologies key principles to guide my quest to ethically represent the life experiences of those who were adopted intercountry and transracially.

Noting the history of forced separation of Indigenous children in residential schools, then in placing them for adoption in non-Indigenous families as part of the 60s scoop, I came to realize that I had first to understand the ways Indigenous children were raised — before the first contact — to be able to understand how such separation impacts the structure of Indigenous communities.

This comes in line with the calls of Margaret Kovach for questioning what knowledges we favour in our approach to research. I learned that during the pre-colonial time, whenever a child was deemed in need, the whole community used to stand up to provide care while preserving the child’s connection to the language, culture and roots.

This practice aligns with the provisions of the United Nations Guidelines on Alternative Care, published in 2009, that emphasize the right of the child to community-based family care. Placing the separation experience in its historical context has helped me to understand how the world constructed the adoption practice as a political weapon to deconstruct Indigenous communities. All colonized countries copied this model. The practice was not meant to serve the best interests of the child.

What is my connection to the research question?

Am I adopted? It is a question that I was invited to answer every time I introduced my research project. While the evident answer is that I am not adopted, I felt the need to articulate my voice, as a researcher and an activist. Why I am doing this research?

Being aware of one’s own subjectivity, instead of denying it, offers a better space for others’ subjectivity. For me, the myth of objectivity exists only in the mind of people who are not able to walk in the shoes of others. It is in that context that I discovered autoethnography as a research methodology described by Carolyn Ellis as a way that “connects the autobiographical and personal to the cultural, social, and political.”

In parallel, I want to explore the risks that one might be subject to when sharing publicly stories of vulnerability. This is how I found myself performing my autoethnography, first to articulate my self-location and second to undergo the same process that I am inviting my participants to live through. The two experiences were very insightful to understand the type of risk associated with my research methodology.

A Draft Story of Invisibility (1), 2017, Concordia University.

A Draft Story of Invisibility (1), 2017, Concordia University.

In those performances, I shared personal stories of living as a child in Lebanon at times of war and later as a child protection advocate. I tried to establish a conversation with the audience and invited them to share their own stories as well.

Blurring the fine line between authentically telling my story and delving into the narratives of others was not without risks. I learned that the minute I shared my story it was subject to interpretation. I came to understand that the essence lies in approaching research ethics by deepening my self-questioning.

How to mitigate harm?

Performing my own stories has invited me to create a list of questions rather than answers. Sharing this list of questions is an invitation for emerging researchers, like me, to think thoroughly —not only about their research methodologies but also about their connections to the research topic, the research questions and, mainly, the participants.

- What are the ethical concerns evolving around the risk of voyeurism, honesty, personal bias, personal limitations, confusions, emotional reliability, memory and history?

- When is someone ready to share a personal story in public?

- How to decide how much of a story to share? In what way? What about aesthetics?

- How to address difficult stories?

- How to ensure safety for the storyteller and the audience?

- How much does the story represent the reality or the revisited reality?

- How to honour their life stories?

- Do I have the right to speak? On whose behalf?

- Who am I in all of this?

While there is no recipe for the questions, Shawn Wilson calls to approach research as a ceremony by establishing a common ground where the researcher writes in the first person to blur the line between ‘I’ the person and ‘I’ the academic. Research becomes a story that honours the readers of the story, the storyteller and the researcher.

About the author