Maya Hey works across disciplines as a researcher, foodmaker, and educator with backgrounds in the culinary arts, food science, and community building. As a Vanier Scholar (SSHRC), Maya is pursuing her doctorate in Communication Studies at Concordia. She studies fermentation and uses feminist theories to better understand discriminating tastes and practices. With more than 10 years of experience facilitating discussions around contemporary food issues, Maya has developed an array of collaborative projects with academic and lay audiences.

Blog post

A different kind of cleaning, a different type of polishing

Cleaning materials matter. These bamboo “sasara” are used to clean the wooden trays in which koji is made. Koji is a mould, so its spores and mycelia get stuck along the inside edges of the trays. These sasara brushes can clean where plastic brushes cannot. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

Cleaning materials matter. These bamboo “sasara” are used to clean the wooden trays in which koji is made. Koji is a mould, so its spores and mycelia get stuck along the inside edges of the trays. These sasara brushes can clean where plastic brushes cannot. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

I arrived at Terada Honké's share-house, or informal dormitory, at the peak of winter’s cold. It was January, when saké preparations are revved up in full gear, that influenza was tearing through all of Japan and a nasty cold had acutely taken hold of the brewery. One by one, the brewers were calling in sick for the first time in years.

After observing the shared dining spaces, I noticed that dish soap was nowhere to be found.

“Should we ... just buy soap?” asked one of the other apprentices.

But nobody answered. Each of us, in our varying degrees of outsider, were hesitant to impose our “common sense” onto our host.

“When in Rome ...” smirked the German.

“You mean Kozaki,” quipped the Italian.

To be sure, colds are contagious, but I didn't have the heart to insist that pre-war Japan — and, for that matter, many other parts of the world — didn’t depend on soap as much as us Westerners. Caught between understanding a soap-free household and being skeptical of it, I spent the remainder of my fieldwork picking apart what it means to (be) clean.

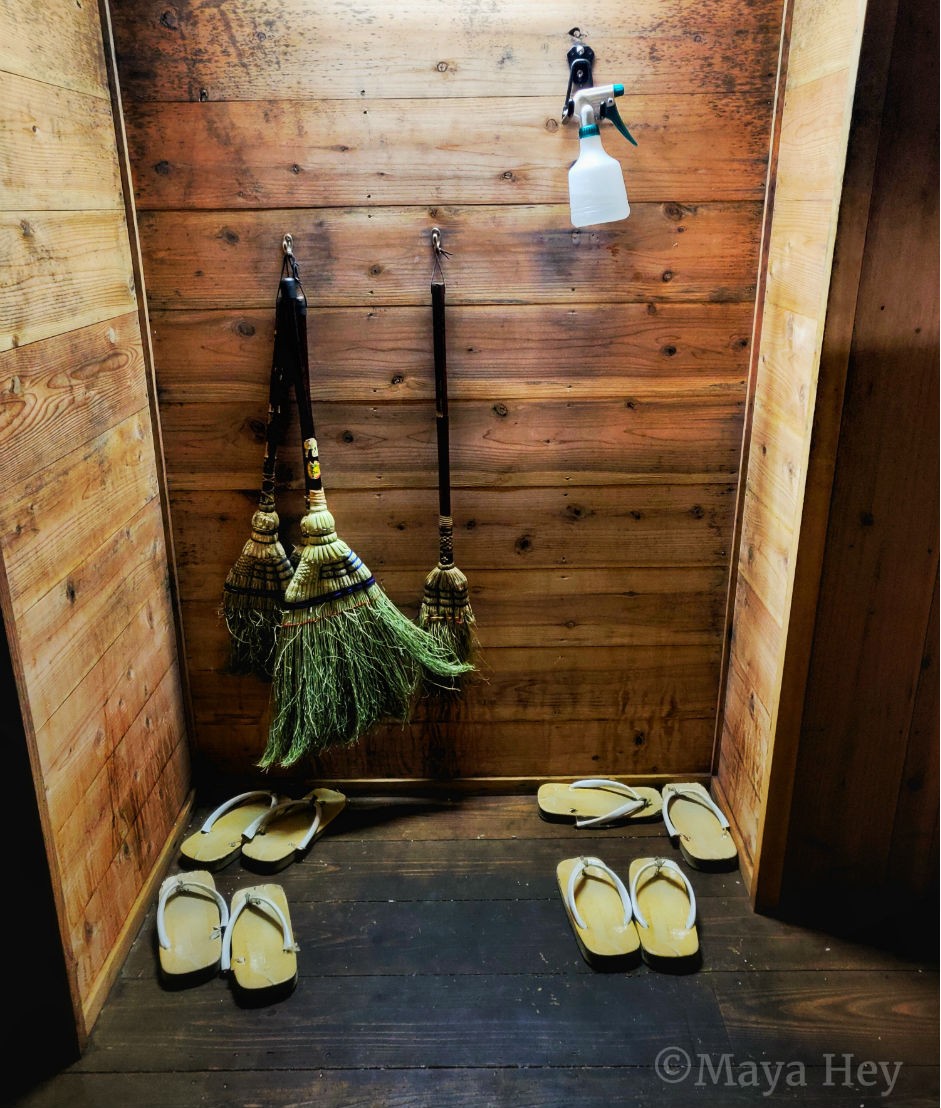

At the entrance of the koji room are brooms, one for the work surfaces and the rest to clear the floors. Just under the light is a small spray container with alcohol, which is used on all hands that enter. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

At the entrance of the koji room are brooms, one for the work surfaces and the rest to clear the floors. Just under the light is a small spray container with alcohol, which is used on all hands that enter. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

As one of two natural saké breweries in all of Japan, Terada Honké does not rely on chemical sanitizers when brewing their saké. Instead, they follow a kind of prevention philosophy that operates from a different worldview towards microbial life.

In the European — or more broadly Euro-influenced — context, the legacy of Louis Pasteur lives on in public health protocols related to food preparation. One of Pasteur’s more famous experiments involved two flasks of meat broth, one of which was kept at sterile conditions while the other was open to the ambient surroundings. Pasteur concluded that the sterile conditions prevented microbial growth, naming microbes as the cause for rot and decomposition.

This became the basis for his namesake food preservation procedure: pasteurization. The process eradicates microbes and extends its shelf life. In turn, food spoils when new microbes — like mold spores — take advantage of the “clean slate,” colonize that food and excrete wastes that are often toxic to humans.

Problematizing Pasteurian logic

Up until Pasteur’s research, people believed that death and disease happened spontaneously. Beer turned murky, herds of livestock died overnight and dog bites turned people mad — all without explanation. In this sense, Pasteur’s findings isolated the causative agent for contamination, which helped demonstrate why people, foods, and animals exposed to those pathogens were later harmed.

That said, it is worth noting that Pasteur’s findings represent one worldview, albeit a dominant one.

While the scientific method helped validate Pasteur’s findings, it didn’t hurt that historical context was on his side: the Napoleonic wars justified the need for sanitary hospitals; friends in the publishing sector promoted Pasteur’s findings over other dissenting voices; and a social movement of incompetent hygienists became the backdrop to frame Pasteur as public hero because he revealed the invisible force behind death.

In other words, Pasteur didn’t “discover” some truth about microbial life; he — and his gang — constructed that knowledge and helped it become accepted as fact.

Petri plates can help isolate microbial species. Underneath the top clear cover is a plate containing nutrient agar — note that the agar in the photograph has been intentionally dyed to better see bacterial colonies forming. Since the surface of the agar is solid, microorganisms can grow on them if incubated properly. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

Petri plates can help isolate microbial species. Underneath the top clear cover is a plate containing nutrient agar — note that the agar in the photograph has been intentionally dyed to better see bacterial colonies forming. Since the surface of the agar is solid, microorganisms can grow on them if incubated properly. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

During my own fieldwork, I relied on feminist critiques of science, which take issue with the objectivity claim that “X” is true because some standard deemed it to be true. Often these standards are arbitrarily set by those in power. As a result, who — or how — that standard was determined is far from politically neutral.

In particular, I follow the ideas of feminist thinker Donna Haraway, who argues that knowledge is situated and made to be true instead of automatically true. She calls playing the objectivity card “the god trick” because the only way to explain truth is to evoke some invisible, all-knowing power. Why is something true? One might say because it’s objective. Because gods can see everything from nowhere.

But it is impossible to have an aerial view that can know everything. Our perspectives as humans are partial and dependent on where we stand in society, as raced, classed, gendered, situated people. So rather than blindly accept Pasteur’s finding as absolute truth, it would be better to acknowledge that his findings are situated in the context of colonial Europe.

Situated knowledge also helps me understand my experience at Terada Honké as being situated in a particular context, instead of judging my experiences as categorically right or wrong. During the work day we wash our hands and spray our hands with alcohol before each task. But, because there isn’t the belief that chemical sanitizers will save us from a spoiled product, the brewers must do more work to create optimal conditions for the target microbes.

The stakes are higher without a safety net.

Redefining Clean

Imagine two petri plates, one sterile and one already colonized by microbial life. Petri plates are designed to grow microorganisms on them so that they can be studied in a laboratory context; from the microbe's perspective, it’s like open land for grabbing. What happens when you introduce a new microbe to both plates? Of course, much would depend on the exact species, but the sterile petri plate will likely be colonized first. Why?

To put it simply, there are more resources available — like nutrients or space — for the new microbe to establish itself. This concept was determined in the late 1800s, when Elie Metchnikoff used existing bacteria to ward off cholera. The existing bacteria interfered with the growth of new bacteria, acting as a kind of protective barrier.

Applying this idea back to the work at Terada Honké, the lack of chemical sanitizers — or the practice of propagating wild starters — creates the ambient conditions for work surfaces and workers to be covered in existing microbes. The work of the brewers, then, is to cultivate that protective barrier of existing microbes and letting them flourish.

In this sense, clean is not a state of emptiness. It is to manage what is already there and to do so with the foresight of preventing future messes.

Thus their “prevention” system operates differently; the baseline for “clean” isn’t a status to achieve. It is a verb. We clean frequently and precisely, with attention to details like scrubbing with well water, rinsing and immersing in boiling water, or using specific tools that get into crevices that plastic cannot — like the bamboo sasara brush — or setting tools outside to expose to the wind and UV rays of the sun.

I heard brewers joke that 30 per cent of the work is actually brewing, with the remaining 70 per cent as cleaning. Rather than follow the Pasteurian logic of eradicating all species, Terada Honké embraces the wild and the unpredictable to create thriving communities.

'Polishing the Heart'

Fermentation is the very stuff of working with, not on, microbial life, and the logic of Terada Honké is to create the best environment for human and microbes to support each other.

In my first weeks working at the brewery, I found it slightly shocking that most of the brewers did not — or could not — drink alcohol. I had assumed that the brewers were there, in part, to enjoy the taste of natural saké.

In conversations with several brewers, I found that a stronger reason for why many return for the seasonal work at Terada Honké had to do with their fermentation philosophy of being in service of others, including other species and other humans.

When asked about why he continues working with Terada Honké, one brewer explained that the saké-making process was proxy for practicing how to be a more mindful, selfless human. He calls it “polishing the heart.”

Another brewer emphasized that the purpose of Terada Honké was to help people grow. To have fun with one another. To give thanks to the water. To promote local farmers producing organic rice. To practice these forms of support on a daily basis.

“It’s a kind of training, you know? It’s here that I refine who I am,” said the brewer.

Head brewer and president of the brewery, Masaru Terada, cleaning the inside of the steaming basket used to make brown rice saké. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

Head brewer and president of the brewery, Masaru Terada, cleaning the inside of the steaming basket used to make brown rice saké. | Copyright: Maya Hey.

Working with the brewery helped me understand the importance of working with microbes, rather than sterilizing them out of existence.

Terada Honké uses fermentation as a philosophical model for living together with microbial life, without exerting absolute control over the fermentation process. The brewers focus on building environments in which various species can thrive across difference.

My hopes are to use the embodied experiences I had in Kozaki to think through collaborative, non-extractive futures, so that we do not resort to dominating or exterminating what we cannot see or easily understand. This experience may be the starting seed for envisioning a collective ethic that spans different kinds of species.

It turns out that I also caught “the January cold” within my first week of arriving at Terada Honké. When my fever peaked, the brewery’s matriarch brought me warm amazake, a sweet fermented rice drink that functions in the same way that Western foodways have relied on chicken soup for ailments.

Looking back on that moment, catching that cold was a way to check my own humanly ego and see the value of practicing humanity towards others who might be suffering. Now that I’m wrapping up my fieldwork here in Kozaki, I see that I am blessed to be surrounded by such vitalizing and convivial communities, both human and microbe.

About the author