Nikola Stepić works in the fields of Film Studies, English and Art History. His current research deals with the city as both a readable interface of desire and sexuality, and as a set of technologies that contribute to the formation of sexual identity. Nikola has published and presented widely on his interests in gender and sexuality studies, material cultures of masculinity, popular culture, porn studies and HIV/AIDS. His work can be read in Angelaki Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, the European Journal of American Studies, The Journal of Religion and Culture and others. An international student from Serbia, he resides in Montreal.

Blog post

Gaga for Gaga

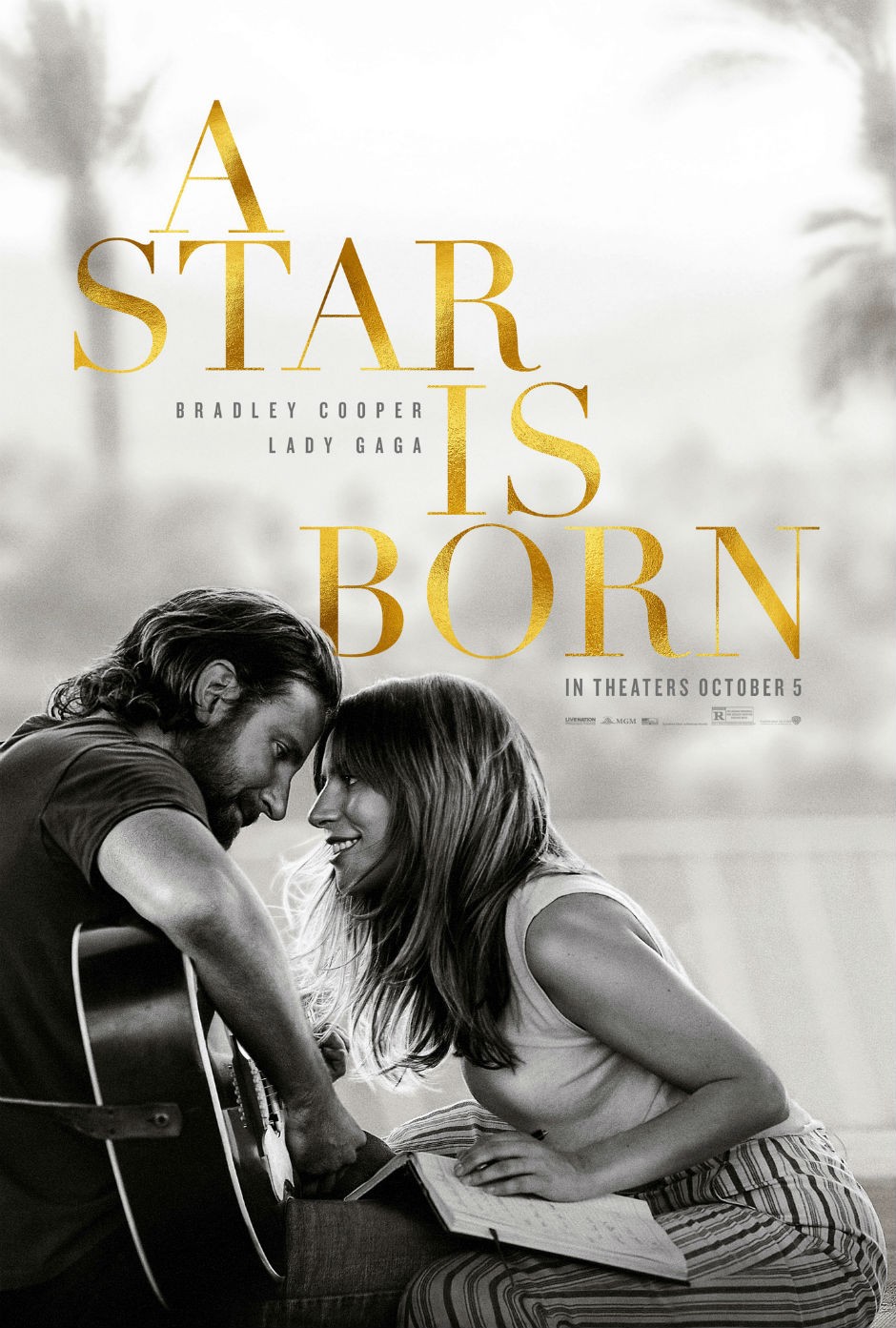

Photo: Warner Bros. Design by Concept Arts.

Photo: Warner Bros. Design by Concept Arts.

When the poster for the Bradley Cooper-directed A Star Is Born was projected at the Montreal premiere, minutes before the film would start, the audience erupted in cheers and chants.

With that, the event quickly turned into that most hallowed of queer spectatorial practices, the veneration of the sublime diva. With her film debut, Lady Gaga has become the latest in a long line of female entertainers whose acting turns in the legendary story of fame and loss have mirrored their appeal to sexual minorities in the real world.

The role Gaga plays in the film was originated by Constance Bennett in the 1932 film What Price Hollywood?, directed by George Cukor. The storyline of each subsequent adaptation, retitled as A Star Is Born, follows the same contours: a popular male entertainer begins a romance with a talented female ingénue, enthusiastically supporting her ascent until her stardom eclipses his.

The relationship is rife with domestic conflict and further complicated by his alcoholism, and culminates in the male protagonist’s suicide. In other words, it’s pure melodrama as the events of the story play out like destiny, accentuated by histrionics for emotional effect, and privileging the story’s domestic setting while simultaneously reveling in pop culture sensationalism.

The perennial appeal of the story is evident by the fact it has been remade no less than four times, starring Janet Gaynor and Fredric March in 1937 (dir. William A. Wellman), Judy Garland and James Mason in 1954 (dir. George Cukor), Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson in 1976 (dir. Frank Pierson) and finally, Lady Gaga in 2018.

Notably, the 1954, 1976 and 2018 versions reimagine the film as a musical, while the 1976 and 2018 versions jettison the Hollywood setting in favor of the music industry. That said, it is remarkable how little the story has changed since the original iteration.

The rapturous reviews this latest adaptation has received are well-deserved. The two leads are more than compelling, Cooper’s direction is assured, and the musical cues are powerful. It is Lady Gaga who steals the show, however, making us forget about her larger-than-life persona as we follow her character Ally's meteoric rise and tragic relationship.

More to the point, Gaga’s relationship to queer culture as both its advocate and manifestation aligns her with Garland and Streisand in a narrative that makes us root for the star as she is forced to navigate the same cultural landscape that has only ever allowed queerness to be represented tentatively, if at all.

In a paper published last year by the University of Priština’s Collection of Papers of the Faculty of Philosophy, I argued that Lady Gaga’s status as a queer icon may be traced to how her performances (musical, filmic and otherwise) oftentimes flirt with the notion of “queer shame,” or queer culture’s roots in disavowal, violence and death.

In that sense, she becomes a stand-in for the journey toward “pride,” as both a political bottom line best encapsulated by the phenomenon of the Pride Parade (or Gaga’s own manifesto, the anthem “Born This Way”), and a collective means of dealing with trauma.

Much like David Halperin interprets the stars of Mildred Pierce and Mommie Dearest (Joan Crawford and Faye Dunaway, respectively) as cathartic conduits for overcoming familial strife in his book How to Be Gay, the persona of Lady Gaga invites queer spectators starved for representation to imagine themselves in the star’s image.

The different adaptations of A Star Is Born profited from similar kinds of interaction with the actresses’ personas. In his seminal study Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, Richard Dyer writes that Judy Garland exhibits an androgyny laced with sex appeal, while Barbra Streisand exhibits her usual work ethic and the desire to remain in control.

The latest version of the film finds Gaga working in a drag bar, her timid persona juxtaposed to the dynamo alumnae of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Shangela and Willam. I would argue that the drag queens are in fact stand-ins for Lady Gaga the pop star, hinting at the extra-filmic relationship she fosters with the queer community.

Moreover, their presence anticipates the transformation Ally undergoes as her career veers into pop, the notion of the (drag) performer as a construct mirroring the Garland and Streisand’s strategies as female performers under the pressure of capitalism and its attendant logic of patriarchy.

Thus, A Star Is Born finds Lady Gaga reimagining her alliance to the queer community in ways that feel fresh, yet are built on the scaffolding of previous films. The trauma and sadness of the woman who finds herself between two incongruent lovers, a man and an entertainment industry, can only be mitigated by her uncompromising showmanship and work ethic.

In fact, it is in the diva’s stepping out onto the stage, whether it’s Judy Garland with “The Man That Got Away” or Lady Gaga with “I’ll Never Love Again,” that the joy and sadness in realizing the limitations and the emotional labour in building one’s identity are brought to life and beautiful music.

Wayne Koestenbaum, in his iconic book The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire explains queer people’s affinity to larger-than-life divas by making a connection between the stage performance and the process of coming out. It is a moment that promises reinvention, empowerment and, most importantly, a receptive audience, or a community.

About the author