Maya Hey works across disciplines as a researcher, foodmaker, and educator with backgrounds in the culinary arts, food science, and community building. As a Vanier Scholar (SSHRC), Maya is pursuing her doctorate in Communication Studies at Concordia. She studies fermentation and uses feminist theories to better understand discriminating tastes and practices. With more than 10 years of experience facilitating discussions around contemporary food issues, Maya has developed an array of collaborative projects with academic and lay audiences.

Blog post

Microbes: Good or bad? (Or, neither?)

Why do you wash your hands, and what exactly are you washing off?

You might answer germs. From a young age, we’ve been taught that washing our hands gets rid of the “bad” germs. And, germ theory dates back over half a millennia, stating that invisible microbes like bacteria, yeast, and mold spores can make us sick.

When we don’t think of Salmonella and Candida in the context of illness and infections, we often associate microbes with decay and rancidity. With an imminent threat of spoiled and rotten foods, no wonder we’re quick to label microbes as nasty or unfriendly.

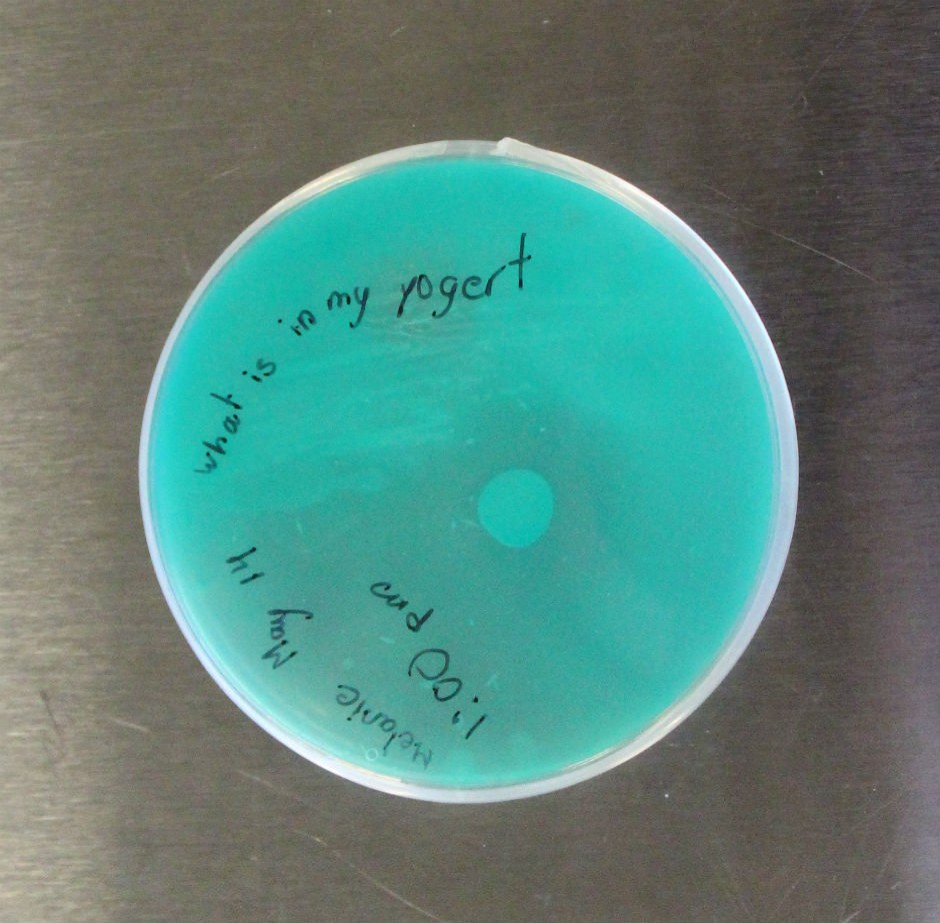

Snapshot from a children’s workshop exploring

the bacterial species in everyday yogurts. | Photo: Maya Hey

Snapshot from a children’s workshop exploring

the bacterial species in everyday yogurts. | Photo: Maya Hey

Currently, the media buzz around “friendly” microbes makes them seem like microscopic saviors. In terms of health, these “good bacteria” are claimed to “boost weight loss,” improve brain functions, and save the planet from our plastic habits. Often under the scientific heading of “probiotics” (where pro- is the prefix for good), these microbes seem to be teaming with support for your gut, your body, and your life. In the context of sustainbility, yeasts are hailed as the next-big innovation tool, engineering molecules like leghemoglobin (to mimic blood-like taste of animal meat) to circumvent the atrocities of a burger-fueled food industry.

A good/bad label becomes shorthand for yes/no interactions with microbial life. Yes, I’ll eat that probiotic yogurt. No, I won’t touch that raw chicken without a glove. We rely on these good/bad labels to make sense of the world around us, but these categories also shape more general attitudes towards what we cannot easily see, sense, or understand. In turn, we’ve built a false sense of security based on the illusion that we can control and master all.

We’re not in control, and increasing amounts of evidence point to microbes influencing human behaviour. So, if we’re not in charge as much as we think we are, then what are the downsides of continually using good/bad labels to describe microbial life?

The Limitations of Good/Bad Binaries

Sometimes, labels contradict each other. The bacteria Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, for example, are hailed as a probiotic when they’re found in yogurt. When they’re found in beer, they produce an “off-flavor” and the entire batch is considered spoiled. When they’re found in urinary tracts, we’re prescribed antibiotics for the infection. Same bacteria, three different contexts, and a label that doesn’t fit.

E.coli are commonly framed as culprits for foodborne illness, but they’re a crucial part of our intestinal flora that synthesizes vitamin K, a necessary nutrient to help with the body’s blood clotting functions. Labels can limit our understanding of microbes as variable: most microbes are along for the ride, some can even help us, but others can kill. Clearly, microbes are not one thing.

Historically, fermentation has been a tangible way for humans and microbes to interact with one another. Food preservation was a common goal. Actively fermenting milk, for example, was one way to extend the longevity of milk. | Photo: Maya Hey

Historically, fermentation has been a tangible way for humans and microbes to interact with one another. Food preservation was a common goal. Actively fermenting milk, for example, was one way to extend the longevity of milk. | Photo: Maya Hey

While good/bad binaries help organize our worlds into distinct categories, binaries are not equally balanced. They favor one side more than the other, so that a better representation would be good-over-bad, or us-above-them.

In other words, binaries are another way of coding for hierarchies. Those on the top of a hierarchy have more power than those on the bottom. When we think of ourselves “on top of” the microbial world, we fool ourselves into thinking that we can control them. Here’s the catch: microbes can mutate faster than we can develop new tools for controlling them.

Hierarchies get in the way of thinking about humans and microbes as inseparable. Our bodies and our environments are made up of billions of bacteria, yeasts, and molds. We have been living with each other and will continue to do so. In fact, we cannot survive without them.

How to Continue Living Together

We have to stop this good/bad mentality. It’s getting us into trouble and it forces us into an unnecessary competition against microbes. In simple terms, microbes can adapt quicker than humans can enact policy or conduct research. As Dr. Anne Madden describes, microbes can easily exchange genetic material with the equivalent of a microbial high-five, swapping advantageous genes in order to outlive whatever might be immediately threatening.

To be sure, “better to be safe than sorry” can be good advice, but not if it leads to the kind of overkill that eliminates all microbes, including the neutral and the helpful ones. (It also assumes that precautionary consumption is an accessible course of action to all individuals, which is problematic because it presumes everyone has the financial wherewithal to access such precautions.) It can also lead to more fearful realities like antibiotic resistance, because it only takes one survivor species to become capable of passing on that immunity gene to a new generation of microbes.

This does not help us with the long-term plan for living together. We need to reconsider how we work with these invisible forms of life.

Bubbles are a sign of life. How can the hands-on practices of fermentation give us clues for theorizing living together in the midst of cultural ferments and social agitation? | Photo: Maya Hey

Bubbles are a sign of life. How can the hands-on practices of fermentation give us clues for theorizing living together in the midst of cultural ferments and social agitation? | Photo: Maya Hey

Fermentation provides one way to engage with microbial life. It accounts for all of the ambient factors that make up a ferment, and it gives us a hands-on guide for how to interact with microbes beyond good or bad expectations. For example, sourdough bread rises according to the life cycle of its bacteria and yeasts, not according to human schedules. And, the outcome can be a rather delicious one.

What we need is a more nuanced language beyond good and bad relations with microbes. If anything, practicing and theorizing fermentation can perhaps lead us to a different lexicon for describing how to continue living with microbial life.

A bibliographic suggestion for the curious reader

- Ed Yong, I Contain Multitudes: the microbes within us and a grander view of life (2016)

- Alexis Shotwell, Against Purity: living ethically in compromised times (2016)

- Norah MacKendrick, Better Safe Than Sorry: how consumers navigate exposure to everyday toxins (2018)

- Lisa Heldke, “It’s Chomping All the Way Down” (2017)

- Eugenia Bone, Microbia: a journey into the unseen world around you (2018)

About the author