Concordia ahead in satellite competition

Since 2010, a team of Concordia engineering students from Space Concordia has dedicated countless hours to the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge (CSDC). A year and a half into the competition, things are looking good for Space Concordia.

The group, created to promote space knowledge and understanding at Concordia University, counts 50 graduate and undergraduate students from all five engineering departments within the Faculty. Thirty-five of the members are participating in the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge.

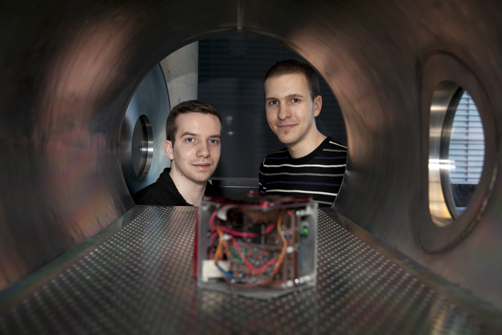

Teams from nine Canadian universities remain in the CSDC. The competition, launched by Geocentrix Technologies Ltd., calls for university students to collaborate in the design, development and building of a CubeSat satellite — miniature satellites with a volume of one litre, and a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms. Built with off-the-shelf electronic components, they are used extensively by universities around the world for space science and exploration.

The Space Concordia team recently completed the design and research phase of the challenge. Following the critical design review, they placed first by a wide margin, landing them in second place overall. If the team can improve their ranking by the end of the competition this fall, Concordia could become the first Quebec university to launch a CubeSat into space.

The satellites entered in the competition are required to have a scientific purpose. After appealing to the Concordia community for suggestions, it was voted that Space Concordia’s satellite would investigate the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), an area where the Earth's inner Van Allen radiation belt comes closest to the planet’s surface.

“The South Atlantic Anomaly comes really close to the coast of Brazil,” says Greg Gibson, Space Concordia’s vice-president, external. “It’s a hazard for aircrafts and satellites because of its high radiation. So our satellite is going to investigate some of the properties of the South Atlantic Anomaly, like the temperature and density of the plasma.”

Several instruments on the satellite will investigate those properties. One of these is a Langmuir probe, an instrument used to determine the plasma’s temperature, density, and electric potential. There will also be a particle counter, used to evaluate the type of radiation in the plasma cloud. Another instrument is the nanowire gas analyzer. This tool is used to determine which gases can be found in low earth orbit.

“We’ll be looking to add data collected from other satellites, but also see if we can find trace amounts of other gases that haven’t yet been discovered in this environment,” says Nicholas Sweet, President of Space Concordia.

In the coming weeks, the Space Concordia team will enter the assembly, integration and testing phase. At this point, the satellite is built, tested and perfected. This comes with the challenge of outfitting the satellite to withstand the harsh conditions of outer space.

“There is a phenomenon called outgassing,” says Sweet. “If you put a regular object into the vacuum of space, small pockets of gas within the material will expand and pop, ultimately breaking the object. So we need to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

To do so, the team must only use space-qualified material, which may have been tested and approved already, or the teams can test each component of the CubeSat in a vacuum chamber on campus that can be made to simulate a space environment.

Other than outgassing, there is a thermal aspect to the design. The team at Space Concordia must ensure that the satellite rotates properly so that it does not overheat. Then, they must take radiation shielding into account.

Despite their recent accomplishment, the Space Concordia team knows that the toughest part is yet to come. “For the rest of the competition, I want to make sure that this success doesn't make us feel like we can relax,” says Sweet. “We did a great job, but we still have to build the satellite, and that's by far the most difficult and time-consuming part of the whole competition. We only have six months to build everything, and after a year and a half of design, that feels like no time at all!”

The winners will be announced in September at an event marking the 50th anniversary of the launch of Alouette 1, Canada’s first ever satellite. Arrangements will then be made to have the winning satellite launched into space.

Related links:

• Canadian Satellite Design Challenge

• Space Concordia