Understanding student drinking

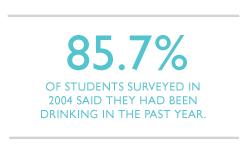

Ask people to think of stereotypes about university life, and they’ll immediately come up with excessive drinking.

Yet of the estimated 40 per cent of Quebec university students who binge drink, most abandon such behaviour after brief experimentation. Only some student drinkers develop alcohol-use disorders later in life, but in order to help students reduce the risk of developing such conditions, it’s necessary for researchers to determine precisely what differentiates these drinkers from others. That’s where Roisin O’Connor, a professor at Concordia’s Department of Psychology, comes in.

O’Connor, who joined the department in 2009, is a leading-edge researcher studying the underlying causes of substance use among university students. Key to her research is understanding the foundations of students’ individual incentives for drinking to excess.

“Heavy drinking behaviour,” O’Connor explains, “is really coming from two different sets of motives. Some people are doing it to have fun and enhance positive moods, other people are doing it to cope with negative feelings.”

In this distinction lies the meat of her research. What she has discovered, following a series of studies that have appeared in a variety of journals on addiction and psychology, is that there are two types of drinkers that are distinguishable with respect to thoughts about alcohol and emotional experiences. The first type, who can be thought of as those who are particularly “reward-responsive,” looks forward to the pleasure and excitement that comes with intoxication. The second type of drinker, who can be thought of as more “anxiety-prone,” drinks to soothe negative emotions like tension or anxiety.

Investigating personality and cognitive factors central to this latter risk pathway, which is called a “negative reinforcement pathway,” is central to O’Connor’s ongoing research. She describes these drinkers as “individuals who are inhibited and typically characterized as being in control, but who may also become very disinhibited when they are emotionally distressed. These are the people who are going to be at risk. The combination of being anxious or inhibited and being impulsive when upset leads them to disregard the negative effects of alcohol.” By ignoring alcohol’s negative consequences, they make themselves vulnerable to continuing dangerous drinking habits into their post-university lives.

O’Connor’s research is in part concerned with what she terms the “negative consequences” of drinking that students may experience: specifically events such as unplanned sexual activity, driving while intoxicated, involvement in physical assaults (either as aggressor or victim), or decline in academic performance. Perhaps O’Connor’s most startling finding is that those who drink to enhance positive moods encounter harmful outcomes of binge-drinking, whereas those who drink to cope are just as likely to experience negative consequences, but without drinking as much.

“People who are more inhibited and anxiety-prone, drinking for coping or tension-reduction reasons,” she explains, “are at specific risks for negative consequences. It doesn’t seem to matter how heavily they’re drinking: They experience the consequences regardless. This may have something to do with how and when they are drinking. For example, they may be consuming alcohol very rapidly and may be doing this when they are emotionally distressed.”

This discovery is exciting because it reveals what O’Connor calls “a whole other pathway to problem drinking at this age,” which helps researchers better prepare prevention programs to meet the needs of these student drinkers, who may not immediately stand out as individuals who are at risk for problem behaviours.

“We need to slow down the impulsivity of drinking behaviour in the moment,” O’Connor says. “It’s not that people don’t have all the information about risk — it’s teaching them ways to engage that information in the moment when they are distressed and alcohol is available so they can make better decisions.”

Related link:

• Concordia's Department of Psychology