Fluid thinking: hard results

This year’s Governor General Gold Medal goes to PhD recipient Ramin Motamedi. His extraordinary work in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering put him at the head — not just of his class — but of all Concordia graduate students at this fall's convocation.

Every year, the Office of Graduate Studies circulates the names of about 80 graduate students whose dissertations were deemed excellent or outstanding. Each Faculty determines which two of their eligible students should be selected and a committee of representatives from all four Faculties makes the final choice.

“When I saw he was on the list of eligible students, I wanted to recommend him because of both the completeness of his thesis, and the usefulness of this research,” says Motamedi’s supervisor, Associate Professor Paula Wood-Adams.

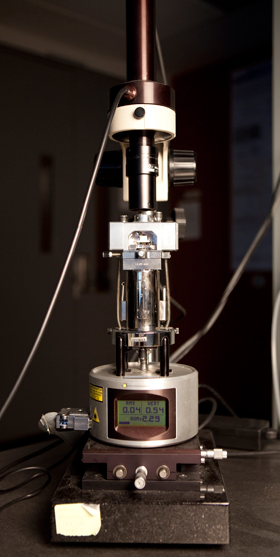

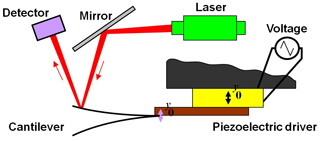

Motamedi’s research project, Microcantilever-based Rheology of Liquids, developed a methodology to determine properties of minute amounts of higher viscosity fluids. Motamedi took five years to complete his research, which required major modifications to the atomic force microscope (AFM) in Wood-Adams’s Laboratory for the Physics of Advanced Materials.

His research has just recently been published in the Journal of Rheology. Wood-Adams is sure that his methodology will have wide applications, especially where the liquid to be analyzed is only available in minute amounts. For instance, with biological fluids. By developing a systematic and extensive set of data on such fluids, researchers might be able to synthetically produce biological liquids for use in medical interventions.

The AFM is essentially a blind microscope. While most microscopes use lenses and magnification to capture images, the AFM allows researchers to analyze the exterior of any material, natural or synthetic, through virtual touch. The AFM’s tiny sensors tap the material and relay information on how hard, elastic, smooth or reactive its surface might be under various conditions.

Motamedi’s challenge was that liquids don’t really have surfaces.

He describes the research project that Wood-Adams proposed as the most intriguing among the ones he was presented when applying to doctoral programs in Canada. Wood-Adams had seen similar research dealing with gases, but no one had attempted to work with liquids more viscous than water.

His system modified the AFM to actually plunge the sensor into the liquid, measuring its properties while moving through, instead of resting on, the material.

Motamedi, whose background is in fluid mechanics, had to figure out how to adapt the equipment, purchased with Canadian Foundation for Innovation funds shortly before he started his research, for studying liquids. His entire project was really a matter of perseverance.

“It was so difficult at the beginning,” recalls Wood-Adams. “The system was hard to modify and it took a lot of courage.”

To properly assess the movements of the sensor in the liquid, Motamedi also had to become proficient at solid mechanics, a field in which he had limited experience during his previous academic work. He also studied rheology, a science that deals with the reactions of complex materials when force is applied. “Think of a tube of toothpaste; it’s solid, and becomes liquid when you apply pressure,” explains Motamedi. He also developed ways to collect and measure data with his modified equipment, and to learn more about data processing.

Wood-Adams is impressed with the breadth of Motamedi’s research. “People who are good in one area are generally are not very good at the other.”

Motamedi takes his multi-faceted approach in stride, “it is not very easy to find a subject that deals with only one science,” he says. “You have to combine them, which means learning another field.”

To accept his medal, he will be flying from Calgary, where he’s already using his newly acquired knowledge of reology in the oil industry. Potential drill sites are flushed out using mud, heavy enough to clear out smaller rocks and other debris. Motamedi’s expertise helps determine how that process should occur, examining the properties of the mud and the force required, and the most efficient way to get the desired result. Although Calgary is colder than Montreal, and a great deal colder than the Iran of his childhood, using his knowledge to bring about practical change in industry is exactly where he wants to be.