News release

Cheaters sometimes prosper — on Facebook

What does it mean to cheat in a Facebook game like FarmVille? Is it any different from breaking the rules in a traditional videogame like World of Warcraft? New research shows that players often dismiss the seriousness of social network games — meaning cheating isn’t so serious when it’s done on Facebook.

In a paper recently published in New Media & Society, Concordia communications researchers Mia Consalvo and Irene Serrano Vázquez polled 151 social media gamers between the ages of 18 and 70. They asked them to respond to questions about why people would choose to cheat on a social media game.

They wanted to know:

- How do players define cheating in general?

- How do players define cheating in social network games?

- What cheating-related practices do players engage in while playing social network games?

- How is cheating in social network games conceptualized differently by players, compared to cheating in more traditional console- and PC-based games?

Motives vs actions

The responses break down into two main categories. The first consists of players who define cheating in a social network game as breaking with the social behaviour that is expected of players. In other words, to cheat is to gain an unfair advantage by the use of different methods or to do something socially irresponsible.

The second group is made up of those who define cheating as simply playing outside of the formal game rules.

“Clearly, rules are not the same thing for every player,” says Consalvo, a professor in the Department of Communication Studies who holds a Canada Research Chair in Game Studies and Design. “For some participants, specific actions or practices do not determine what is cheating — instead, they define cheating by the purposes or motives behind those actions or practices.”

The majority of survey respondents reported at least some kind of cheating: they admitted to playing social network games to help friends (65 per cent) or family members (58.3 per cent) advance their scores, and to asking friends (52.1 per cent) or family (50 per cent) to play a social network game in order to advance their own scores, and to adding strangers (53.9 per cent) to do the same.

A high number of participants admitted to purchasing currency to advance play (40.2 per cent), creating multiple accounts (31.1 per cent) and logging into someone else’s account (20.6 per cent). The use of cheat codes — a means of cheating requiring greater technical skill — was a much rarer practice among participants, only 8.2 per cent admitted to doing so.

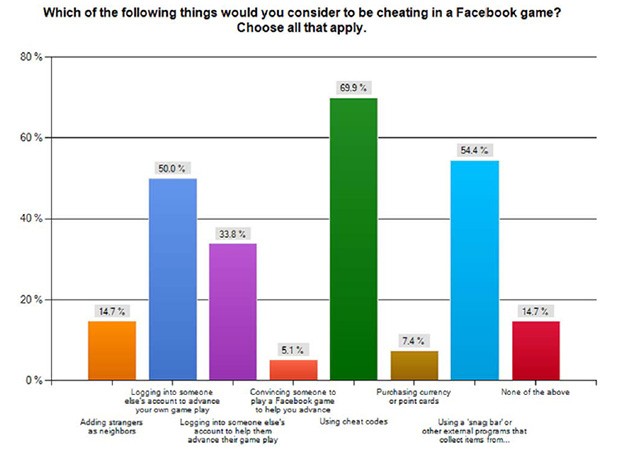

Not surprisingly, the study participants were not quick to criticize various forms of cheating in Facebook games. As can be seen in the table below, the harshest condemnation was reserved for the type of cheating that requires technical know-how.

Cheating in social network games, it seems, is hard to define and varies from player to player — and from game to game.

“Players believe cheating might be different based on the platform on which play takes place,” says Consalvo. “They believe social network games are not ‘real’ games, so you can’t cheat at them.” When Consalvo and Vázquez asked players whether cheating in a console or computer game is different than cheating in a Facebook game, roughly a third of respondents answered that it is different in some way.

Consalvo hopes future studies will consider how playing with real profiles affects players’ game ethic and their attitudes toward various practices. “I’m interested in seeing whether players are less willing to cheat when they play with their real identities, and what that means for the future of social networks.”

Learn more about Mia Consalvo’s research by checking out her new book, Players and Their Pets: Gaming Communities from Beta to Sunset, published by the University of Minnesota Press.

Source

© Concordia University