Rituals of (un)rest

by María Andreína Escalona De Abreu

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Avery Suzuki, MILK

Avery Suzuki, MILK

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

Dexter Barker-Glenn, Stop Request

Dexter Barker-Glenn, Stop Request

i am anxiety

i am explosion i am epiphany1

Julie Glicenstajn's words remind me that in attempting to be a well-rested artist one must succumb to restlessness.

Because what is art if not a reinvention, a transformation, a questioning, or a disturbance of the structures in place? And what is an artist if not a human being with the physiological, psychological, and emotional need of rest?

Rest can, and should, take many forms; it can manifest itself as taking care of each other, individually and collectively; but in the artist’s labour it is often overlooked. Either it is difficult to include in one’s routine because we are always creating, reflecting, emoting, or it does not comply within the oppressive systems we live in.

Through the art of Avery Suzuki, Dexter Barker-Glenn, Belén Catalán, and Julie Glicenstajn, I reflect upon mental health and the never-ending stigma around it, communal and individual acts of care, and the rituals we follow to “be well.” To sleep, to walk, to communicate, to take one’s medication – these might seem to be mundane actions, but the artworks featured in this group exhibition show us otherwise.

Avery Suzuki, Kofun Bed

Avery Suzuki, Kofun Bed

Placed in the York Vitrines, Avery Suzuki’s installation includes two sculptures, Kofun Bed and Milk. The mise-en-scene of the two sculptures together invite the audience to reflect on domesticity and the hidden possibilities behind objects; to imagine and fantasize about our daily rituals beyond the routine, and to disrupt and dismantle the functions associated with the objects surrounding us.

Kofun Bed is displayed horizontally on four wooden legs attached to a frame of the same material, upon which rests a yellow foam mattress with a carved wavy pattern. Although non-functional, the piece is recognizable as a bed and results in a hybrid of both the ritual of sleeping and the ancestral ritual of kofun burials. The piece is a scaled-down depiction of a kofun, keyhole shaped tomb mounds of monumental proportions built for the nobility during the Kofun Period in Japan (ca. 300-710).2

Avery Suzuki, Milk

Next to Kofun Bed, rests Milk. Made of paper, bamboo, and rubber, this sculpture references a traditional chochin lantern. This staple in Japanese domestic furniture gains personality and an uncommon materiality due to the artist’s intervention. The bamboo skeleton and the washi-style paper are covered and protected by poured milky rubber. Both pieces showcased in the vitrine are inspired and informed by Japanese folklore’s tsukumogami, everyday objects that come to life as they are inhabited by kami (spirits). Suzuki’s body of work is an attempt to transform these mundane familiar objects and attain their transcendental and sacred form, or as the artist has dubbed them, ‘spiritual IKEA.’

Barker Glenn, Stop Request

Both reflecting on physical representations of the power of the ruling class, Suzuki and Barker-Glenn create works that evoke traditions or practices from the past while contrasting them with contemporary realities, materials, and rituals. Stop Request references Victorian Europe and North America, where bell pulls were used in almost every upper-class household to summon servants, functioning as an extension of social power. These two references invite the viewer to consider inherited social hierarchies and their material manifestations.

Connected with a system of rubber-coated wire, bells, wood pieces, aluminum-cast body parts like fingers, toes, and a nose, as well as recognizable items like orange slices and an asthma inhaler, Stop Request forms an interdependent system. Molded from the artist’s own body and the objects found in his pockets, the different elements evoke a sensorial experience for the audience. Extending itself in the gallery’s Main Space, the installation allows the past, present, and future to collide. Using the Victorian bell pull in combination with a present-day parallel form, the bus pull bell, this piece draws attention to a simple, yet complex, mechanism that allows humans to voice their demands and to exteriorize their power, or lack thereof.

Barker Glenn, Stop Request

Visitors are invited to activate the piece by pulling the cord(s) which will produce the sound of bell(s). As I reflect on the artist’s intention to critique or reimagine tools of power and communication, I ask: what does that say about accessibility and privilege? For Barker-Glenn subjectivity is key, inviting deeper investigations into the upholding of current social inequities and alternatives to capitalism and class-based systems.

The two artists discussed above both offer new versions of household and communal items that transcend their original purpose to become portals to a new reality. This is a reality where objects are containers for spirits and/or spiritual rituals, in Suzuki’s case; or in Barker-Glenn’s installation, a reality where requesting something by pulling a cord is a call to reflection, to societal change.

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

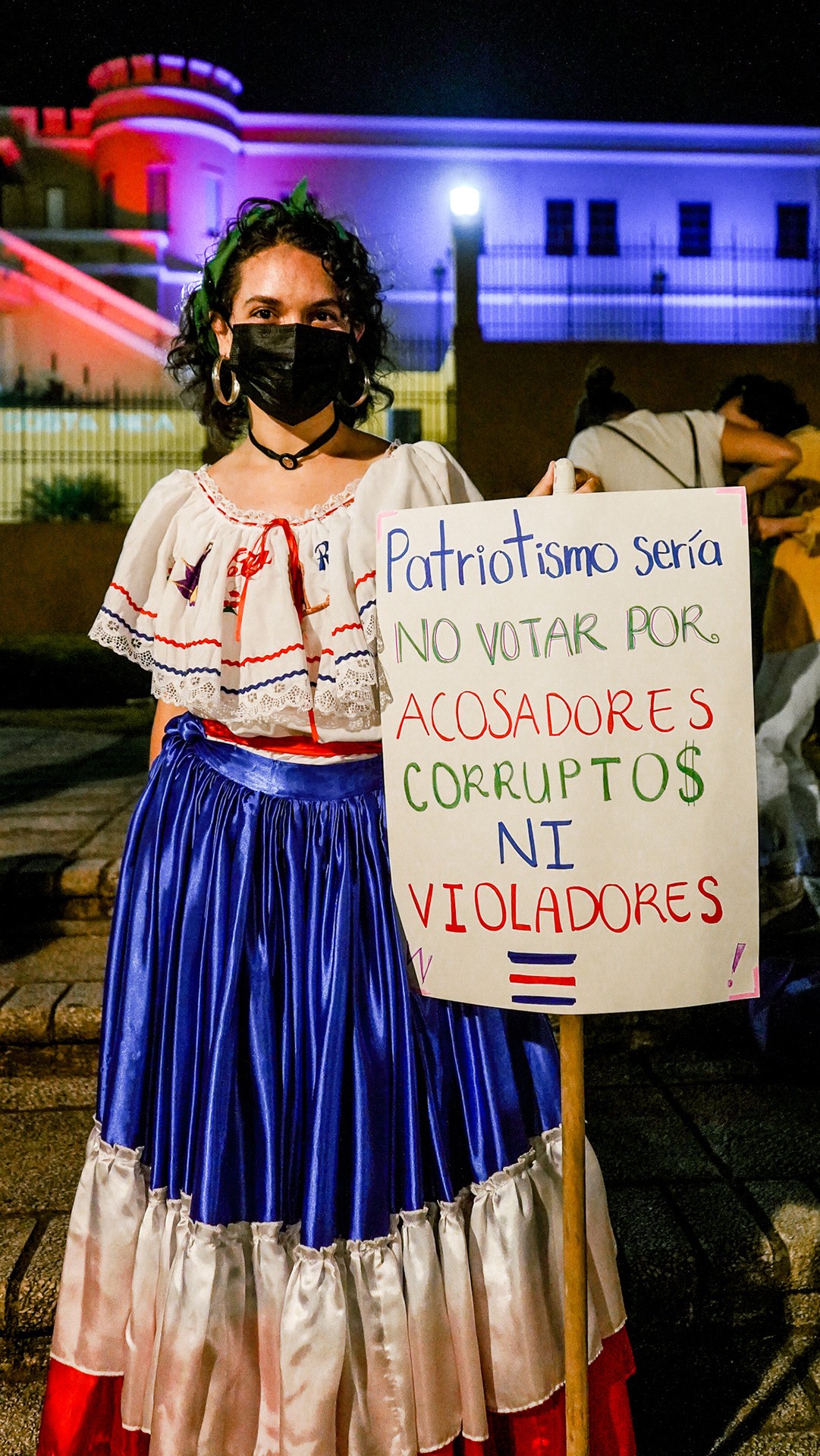

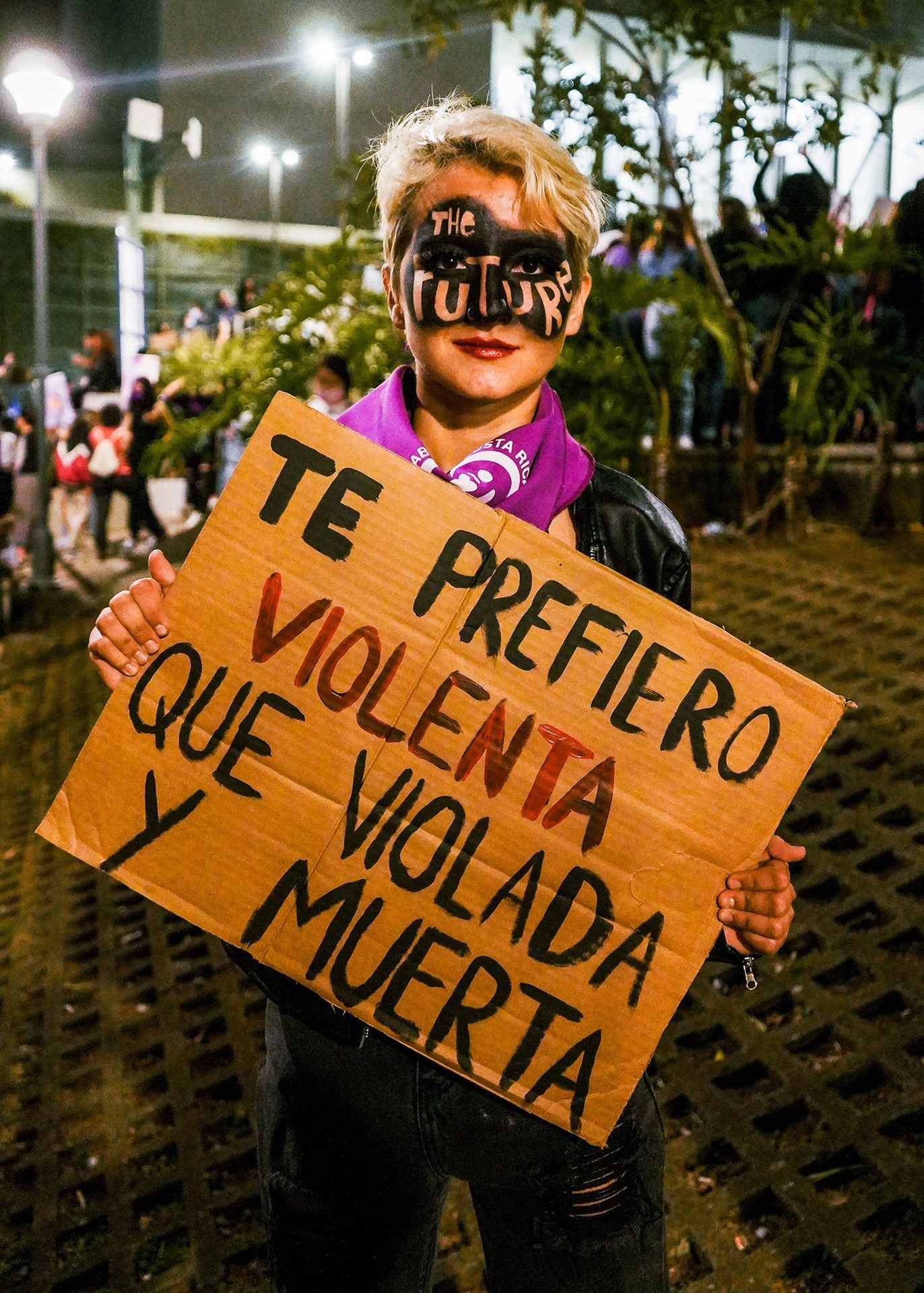

Belén Catalán’s photographic series in the York and Ste-Catherine Vitrines is also a call to critique and question the systems we live in. Te Odiamos Patriarcado stems from a collective act of care, a ritual of unrest: a protest against the patriarchy.

In Catalán’s piece, Te Odiamos Patriarcado [We Hate You Patriarchy], the act of walking is pictured as a strategy for denunciation that will hopefully lead to change. The artist’s artivism and photo-documentary practice aims to bring forward feminist and queer organizing in Costa Rica. This series captures the attendees of a march for Women's Day in the province of San José, Costa Rica in 2022 to raise awareness about the violence and injustices women and members of the LGBTQ+ community face there every day. The six photographs spread over the gallery’s vitrines, York and Sainte-Catherine, confronting the visitors with portraits of proud ticas and ticxs3 advocating for their rights.

After leaving her home country five years ago, Catalán travelled back in March this year, and participated in the march where she documented the power of coming together to create a better collective future. The 2022 March is a continuation of the 2020 call for actions against the rise of gendered violence. Like many other countries in Latin America, there has been “an upsurge in violence against women, as evidenced by violent murders, increased reports of domestic violence and sex crimes.”4 The banners and faces (as seen in the piece No Mas), denunciates the recently elected president Rodrigo Chaves, who was accused of sexual harassment in 2019,5 alongside other social, economic, labour, health, and personal safety barriers that “women in all their diversity" encounter.6

Both a cry for emancipation, Belén Catalán’s photos and Julie Glicenstajn’s installation are connected by their impact and roots in Latinx culture; they advocate for the eradication of ignorant practices and dangerous beliefs, like the disregard for women’s and queer human rights and mental health. Te Odiamos Patriarcado shows the fight against the sanctioned laws oppressing the collective that in turn affect personal spheres. In Glicenstajn’s RUÍNAS, the approach stems from individual experiences, expanding to broader concerns surrounding social access to mental health support and treatment.

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Filling a prescription or taking a daily medication can be read as part of a wellness routine. However, for Glicenstajn taking her antidepressant simultaneously represents care and imprisonment; a dependence she would gladly give up if it did not have such consequences on her survival. RUÍNAS (ruins in Portuguese) is a structure composed of layers of clay bricks, used in Brazil as the primary material for housing and empty antidepressant pill blisters. For a brief moment, the structure will stand tall and sturdy in the gallery's Main Space before being hammered down by its creator. This one-time performance/installation, accompanied by a poem, showcases an architectural inner fragility exploring grief and the impossible notions of normative essentialism in wellness.

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

Belén Catalán, Te Odiamos Patriarcado

Avery Suzuki, Kofun Bed

Avery Suzuki, Kofun Bed

Barker Glenn, Stop Request

Barker Glenn, Stop Request

Cohabiting the gallery and these pages with eight other works, these four installations are brought together in this essay because they all touch upon strategies for survival – to sleep, to walk, to communicate, to take one’s medication – which are portrayed as acts of bravery, crucial healing methods, or investigative tools challenging social hierarchies; endeavours that are far from trivial.

The playful approach to sleep, death, and daily life in Avery Suzuki’s Kofun Bed and Milk, the rewiring of social and power dynamics in Stop Request by Dexter Barker-Glenn, Belen Catalan’s portrayal of social realities bleeding into the private realm in Te Odiamos Patriarcado, and the explosive yet silent presence of Julie Glicenstajn’s RUÍNAS; these artists offer four different proposals on rest, its synonyms and antonyms, that encourage us to reflect on the impacts of one’s actions on the collective. Though seemingly opposite, rest and unrest dance in the same infinite cycle; they are complementary and should be considered simultaneously. As artists, we need wonder and restlessness to create and gather the courage to show the fruits of our labour. As human beings we need the habits, and mental health strategies to survive and hopefully… thrive. To be an artist is to be constantly resting and unresting.

- Julie Glicenstajn, RUÍNAS “, artist statement, USE 2023 submission, 2022.

- “Kofun Period (Ca. 300–710).” Metmuseum.org. Accessed October 19, 2022.https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kofu/hd_kofu.htm.

- Colloquial terms for Costa Rican women and non-binary Costa Ricans.

- Daniela Muñoz Solano. “2020: El Movimiento Feminista Floreció En Todo El País,” Semanario Universidad, December 9, 2020. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/2020-el-movimiento-feminista-florecio-en-todo-el-pais/. All translations by the author unless otherwise noted.

- Sally Palomino. “Grupos De Mujeres Rechazan En Costa Rica Al Candidato Rodrigo Chaves, Señalado Por Acoso Sexual,” El País, February 24, 2022. https://elpais.com/internacional/2022-02-24/grupos-de-mujeres-rechazan-en-costa-rica-al-candidato-rodrigo-chaves-senalado-por-acoso-sexual.html.

- Andrea Mora, “Organizaciones Feministas Convocan a Marcha Contra La Violencia a La Mujer El Próximo 8 De Marzo,” Delfinocr, March 1, 2022, https://delfino.cr/2022/03/organizaciones-feministas-convocan-a-marcha-contra-la-violencia-a-la-mujer-el-proximo-8-de-marzo.

About the author

María Andreína Escalona De Abreu is a Venezuelan visual artist, writer, and independent curator based in Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal and an active member of the feminist collective Soy Nosotras. She obtained a BFA in Fibres and Material Practices at Concordia University in 2022 and has since been developing her curatorial practice as FOFA Gallery’s curator in residence. Escalona’s practice aims to intersect visual, linguistic, textile and printed forms as a means to connect and emote with her community, while offering new perspectives to a wider audience. Her work is a love letter to her Venezuelan roots and Canadian present.