The encounter between OSIRIS-REx and Bennu will last only five seconds. Because of the spacecraft’s distance from earth, it can’t be controlled by people on the ground. It’s all programmed into the vehicle.

“The spacecraft will expand a sampling arm from its body. As soon as the head makes contact with the asteroid, it releases pressurized gas which sets off a flurry of particles,” says Haltigin. Those are captured in a canister. “Think of it as giving a gentle high-five to the asteroid.”

After encountering the asteroid, the stars have to align before OSIRIS-REx can make its way back to earth. “Because the orbits aren’t right, it’ll be hanging in space an extra year or so, somewhere between earth and Mars,” says Haltigin.

The origins of life

“Think of an asteroid as a time capsule,” says Haltigin. “They were formed at the beginning of our solar system and haven’t changed much since.”

Because of that, an asteroid sheds light on some of life’s biggest questions. “You can understand the chemistry of our solar system. We’re hoping to answer questions on how our solar system evolved and how life became seeded on earth,” says Haltigin.

“It’s pretty incredible,” says Haltigin. “Every day I say sentences out loud that even I don’t believe!”

Cosmic goal

Over-and-above the usual excitement of his day job, Haltigin was among 72 finalists in Canada’s search for its two newest astronauts.

“They tested an awful lot of things,” says Haltigin of the experience. The process included logic, ability to work in a team and physical fitness. Those selected will be announced in August 2017 — and that’s just the beginning.

“Canadian astronauts are assigned to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston,” he says.

Alongside American candidates, they train for two years. Part of the experience is at Aquarius, an underwater laboratory off the coast of Florida. “It’s used as a practice facility for living in remote, extreme environments,” says Haltigin.

At the other end, astronauts are assigned to a flight — though as Haltigin explains, going to space is a small component of it. “Your role is to push limits in all directions,” he says.

An education fit for the starry-eyed

“I owe much of my scientific career to my time at Concordia,” says Haltigin. He says Pascale Biron, professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, “called me after class one day. She said, ‘I put your name in for this thing called NSERC. And if you’re selected you’re working for me this summer.’”

Haltigin ended up winning that scholarship. “She was the one who really showed me that science doesn’t only happen in the classroom,” he says.

“She taught me how to observe things, how to ask questions. She really set the foundation for my career as a scientist.”

Tim Haltigin is senior mission scientist at the Canadian Space Agency

Tim Haltigin is senior mission scientist at the Canadian Space Agency

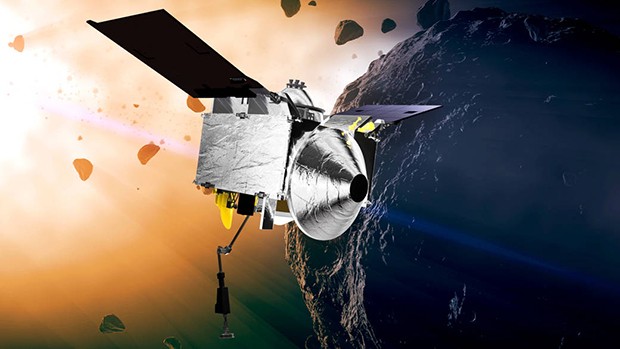

The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is en route to Bennu, an asteroid that might contain answers to so some of our biggest questions — such as the origin of life itself.

The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is en route to Bennu, an asteroid that might contain answers to so some of our biggest questions — such as the origin of life itself.