Nikola Stepić works in the fields of Film Studies, English and Art History. His current research deals with the city as both a readable interface of desire and sexuality, and as a set of technologies that contribute to the formation of sexual identity. Nikola has published and presented widely on his interests in gender and sexuality studies, material cultures of masculinity, popular culture, porn studies and HIV/AIDS. His work can be read in Angelaki Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, the European Journal of American Studies, The Journal of Religion and Culture and others. An international student from Serbia, he resides in Montreal.

Blog post

The grad student diaries

Photo by Anete Lūsiņa on Unsplash.

Photo by Anete Lūsiņa on Unsplash.

The inspiration for this blog post comes from my fellow Concordia public scholar, Younes Medkour, who started a conversation on Twitter about how researchers keep track of the many materials they are ploughing through on their way towards a degree. In light of Younes’ question, I couldn’t help but wonder if we can think beyond citation software like Zotero or Mendeley while at the same time upping our research game through more creative venues.

Enter Letterboxd, a social network built around cinephilia. Combining the usefulness of databases like IMDB and the liveliness of social networking sites like Facebook, Letterboxd offers its users a spiffy interface built around each member’s film diary.

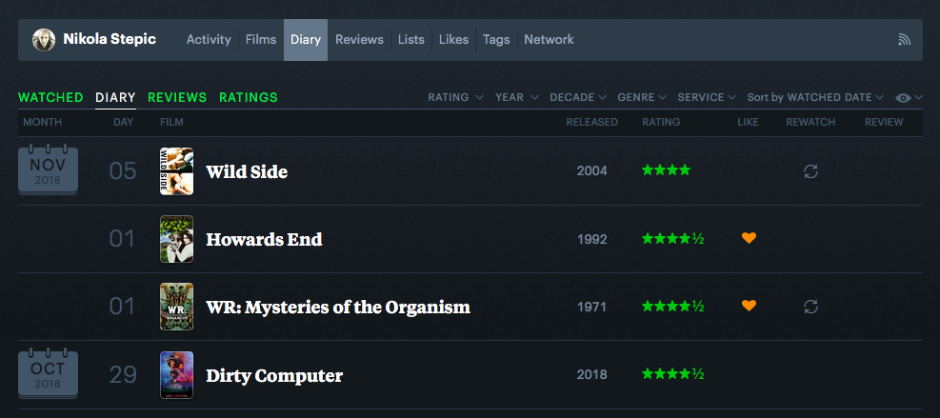

I’ve been using Letterboxd for a number of years now, and my profile allows me to sift through my film diary according to different parameters — chronologically, alphabetically, or even in terms of a film’s overall popularity on the website.

As I’m writing this, my most recently watched film is Sébastien Lifshitz’s Wild Side, which I screened in my class last Monday; the very first film I logged to Letterboxd, on January 1, 2014, was James Franco and Travis Matthews’ misguided-but-fascinating mockumentary Interior. Leather Bar.

The most popular film I’ve seen, according to the website’s algorithm, is Mad Max: Fury Road (dir. George Miller, 2015), while the least popular is Derek May’s NFB-produced 1991 documentary Krzysztof Wodiczko: Projections, about the titular artist’s practice of projecting artwork on architecture, in the process transforming communal spaces. The film deserves a wider audience and can be seen here.

Thinking about Letterboxd and my (over)investment in cataloguing my viewing activity, I am reminded of Joan Didion, whose piece titled “On Keeping a Notebook,” published in a collection of essays Slouching Towards Bethlehem in 1968, seeks to unpack the activity of journaling beyond the mere recording of dates, names and memories.

For Didion, journaling is above all a deeply personal and necessarily creative endeavor, the result representing “bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.”

But isn’t that precisely what research is? It’s bits and pieces of information, quotes and paragraphs and film clips and interviews, all of which are to be united and made to speak to each other at the tail end of the process in ways that they haven’t before. And isn’t this folding of the past and the present, the personal and the public, the governing logic behind both academic research and social media?

Letterboxd allows users to create and share annotated lists of films, which range from helpful canonical reproductions, like MomSaysItsOK’s list of “The 100 greatest foreign language films [according to the BBC],” to, I would argue, even more helpful topical ones, like loureviews’ “Older women and younger men in the movies” or Lyzette’s “Men/Boys Crying.”

I am especially fond of the more personal ones, like loise’s “things my dad has said about movies” or Simone’s list that catalogues their fetishization of writers in cinema. The versatile lists, utilized either to point to a canon, a personal trajectory, or even used as a game where people assign each other films to watch, bridge the cold hard data of logging and the creativity of journaling.

Their social aspect also signals the potential of digital journaling versus the more traditional pen-and-paper model.

Photo by Dmitry Ratushny on Unsplash.

Photo by Dmitry Ratushny on Unsplash.

Of course, Letterboxd is not the only social network that explodes journaling in a public arena. GoodReads is another favourite of mine, as it allows users to log and review books, but also to create lists, join reading communities and book clubs, enter giveaways, and connect to their favorite authors.

Last.FM’s logging tool lets users generate statistics about exactly what kind of music they listen to, when they listen to it and how their listening habits compare to others’. And let us not forget the power of Tumblr, where users post and repost multimedia whose meaning is generated only as the images, text and videos are consumed one after the other, the juxtapositions inspiring endless connections and meditations.

It is no wonder that colleagues of mine have harnessed the power of platforms like Tumblr or Twitter in their classrooms, asking students to post and repost with the hopes of simultaneously producing a meaningful trace and directing the conversation outwardly from their carefully curated courses.

Different disciplines necessitate different approaches, naturally, and there is something to be said about the power of analog journaling — either through lists, agendas, bullet journals or other techniques. But why not turn our techno obsession (and, it should be said, content creation for others to profit on) into a research tool, and mobilize these populist platforms to think about, or even promote, our academic endeavors?

I am certain that this kind of engagement can only improve one’s research and writing — and even if the true meaning of the log is known only to the producer, or if it’s embellished to the point that it resembles fiction rather than reality, it is still a potentially inspiring and useful thing: a piece of work as a piece of art.

About the author