In 1993, veteran Hollywood actors Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon starred in the comedy Grumpy Old Men. Why were they so grumpy? Possibly, along with many seniors, they were agitated and unable to relax. Unfortunately, for those suffering from dementia, such agitation is fairly common.

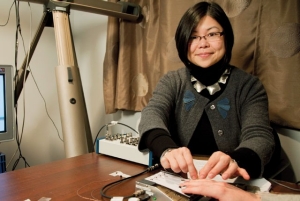

Laurel Young, an assistant professor of music therapy in Concordia’s Department of Creative Arts Therapies, may have one solution. Young is an accredited music therapist with clinical experience in geriatrics and dementia, palliative care and other areas of physical and mental health.

Prior to her music therapy training, as a university student Young had the opportunity to play music in the locked dementia units of a long-term care facility. “I could also awaken those who were very withdrawn,” she says. “I knew I needed to understand more and that’s why I decided to pursue training as a music therapist.”

Young’s initial interest in research came out of an internship where she worked with dementia patients at Toronto’s Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care. While there, she investigated the use of music to stimulate object recognition. It was clear that music stimulated memory and interpersonal connection. “The science is just starting to catch up with the anecdotal experiences that music therapists have been talking about for years,” she says.

She expanded her bio-psycho-social health perspectives into the area of singing and health, yet her passion for working with seniors remained. “With almost all dementias, the music functions of the brain remain intact. Most individuals retain a sensitivity to music, and have the ability to participate in a wide variety of music experiences,” she says. “Research has also shown that both these attributes may be enhanced, even as other capacities deteriorate.”

Creative arts therapies won’t cure dementia, Young says, but by decreasing agitation, stimulating cognition and facilitating meaningful interactions with others, they can significantly improve quality of life for many patients.

She describes a case where the husband was institutionalized and hadn’t spoken for many years. The wife usually visited daily, sharing in much of his care. Young would see this couple in a small music therapy group. Singing gentle songs on guitar and touching the man’s hands, she was often able to rouse him from his languor.

When Young discovered that the couple’s song was Let Me Call You Sweetheart, the results were revelatory. She would sing “Let me call you sweetheart,” and the husband would finish the line with “I’m in love with you,” and then look at his wife. Here was a woman, Young explains, who for years didn’t know if her husband was aware of her presence or anything she did to help him. When the husband acknowledged his wife in that setting, it was moving and meaningful for them both.

“Music is a distinct domain of functioning in the brain that seems to serve a variety of purposes, but we are still discovering its full potential,” Young maintains. “My theory is that if the music functions of the brain are so important, shouldn’t we be trying to maintain these functions to the fullest possible extent?” She believes using creative arts therapies in this way is “not just fun and enjoyable, but clinically indicated.”

As our population ages, we are looking towards overwhelming numbers of people with dementia, yet are not physically, financially, or psychologically prepared for this, Young warns. We have an obligation to provide them the best possible quality of life.

In future, she hopes, “We may be able to understand how music works when other forms of communication have failed, to discover a way to capitalize on this in creative, functional, and meaningful ways. These people will be us — if we live long enough. How will you want to be treated?”

–Beverly Akerman is a Montreal writer.

Patrik Marier, a professor in Concordia’s department of Political Science, is also scientific director of the Centre for research and expertise in social gerontology in Montreal.

Patrik Marier, a professor in Concordia’s department of Political Science, is also scientific director of the Centre for research and expertise in social gerontology in Montreal.

Charles Draimin, professor and chair of the department of accountancy at Concordia’s John Molson School of Business, notes that a segment of the Canadian population is no longer forced to retire.

Charles Draimin, professor and chair of the department of accountancy at Concordia’s John Molson School of Business, notes that a segment of the Canadian population is no longer forced to retire.

Communication studies professor Kim Sawchuk helps fight the attitude by younger generations that older people don’t have a clue about digital technologies.

Communication studies professor Kim Sawchuk helps fight the attitude by younger generations that older people don’t have a clue about digital technologies.

The research by psychology professor Carsten Wrosch has shown that when seniors are trained to write about their life in a positive light, rather than focusing on regrets, they feel better about themselves.

The research by psychology professor Carsten Wrosch has shown that when seniors are trained to write about their life in a positive light, rather than focusing on regrets, they feel better about themselves.

One of the research projects conducted by Karen Li, a professor in Concordia’s department of psychology, found that playing computer games along with fitness training helped improve seniors’ condition.

One of the research projects conducted by Karen Li, a professor in Concordia’s department of psychology, found that playing computer games along with fitness training helped improve seniors’ condition.

Music therapy assistant professor Laurel Young recently received awards from Wilfrid Laurier University and Temple University in Philadelphia for outstanding contributions to the field.

Music therapy assistant professor Laurel Young recently received awards from Wilfrid Laurier University and Temple University in Philadelphia for outstanding contributions to the field.