Dover’s research also examines how injuries affect athletes’ sleep, as well as sleep’s role in recovery time. PERFORM researchers know that some people take longer than others to recover from illness and injury. What they don’t know — yet — is why. “We know sleep is essential for daily activities and functioning normally and it’s something we haven’t looked at enough in athletes,” says Dover. “We spend a lot of time and money on coaching, nutrition and performance enhancement, but we don’t look at sleep.”

Then there’s fear of pain, a factor with proven effects on patient recovery times. It is this deeper understanding of pain perception or pain-related fear that gets Dover up in the morning. Fear of pain and reinjury are well documented in general-population studies: recovering individuals either rehabilitate quickly or slowly, depending on their attitudes to pain. Dover wants to know how prevalent this is in athletes. “Everyone assumes athletes have a high pain tolerance and wouldn’t be affected by something like this, but it’s not true.”

Athletes, Dover adds, are affected by pain dysfunction as much as anyone. The difference between them and the rest of us is self-image. “If a regular person gets injured and they can’t do, say, the triathlon they wanted, it’s difficult because they like training,” he says. “It’s a completely different challenge when an athlete gets injured because it’s their identity — this is their life.”

In the mind

Olympians, like all elite athletes, acknowledge physical risks of competition. What of mental fitness? Mind games have played a huge role in Bilodeau’s ascent to medal podiums. Down the ski trail, the JMSB student mentally recites the words: ‘tall,’ ‘soft’ and ‘keep it.’ “It’s all about putting yourself in the right state of mind to deliver the best performance you can,” says Bilodeau, who works with eminent sports psychologist Wayne Halliwell. Bilodeau says the decade-long relationship has deepened his self-understanding. “I think I’m a better person. I know myself better and when you know yourself, you know how you’re going to react.”

This fits with Theresa Bianco’s definition of sports psychology. An assistant professor in the Department of Psychology, Bianco describes her work with Concordia athletes as a matter of self-awareness. “Performers don’t park their brain in a jar when they go out onto the field or arena or slopes,” Bianco stresses. “They need to be mentally prepared as well as physically prepared in order to perform well. We try to help the athletes figure out what works for them so that they can consistently perform their best under conditions of extreme pressure.”

So are sporting pinnacles reached by some kind of harmonic mind-body-spirit fusion in elite athletes? “At the highest level it is really 80 per cent mental and 20 per cent physical,” says Brisson, who has worked with psychologists on team tactics and distraction control. “I did a lot of imagery practice, rehearsing situations that the opponent would present so you can recognize cues early and make appropriate decisions quicker.”

The psychology behind laying claim to a gold medal is more about focusing on the process than on the goal, says Bianco, who works with 2008 Beijing Olympic Games wrestler Martine Dugrenier, BSc 02, GrDip 08. “You’re like a rock star when you’re at the Olympic Games. There is so much going on around you and it’s really easy to get caught up in all that excitement and start to lose a bit of your focus,” Bianco says. “We work on anticipating all the things that can be distractions. Athletes must feel in control.”

The Sochi Games will exact its price on athletes in several ways. The city on the Black Sea is nine hours ahead of North American east coast time. Those travelling from afar should be mindful of the perils of jet lag, warns Shimon Amir, professor in the Department of Psychology and director of Concordia’s Center for Studies in Behavioral Neurobiology. (For more on the centre, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, see “Sex, drugs and… rats” on page 37.)

An expert in circadian rhythms, Amir notes that maladjustment to time-zone changes could play havoc with athletes’ digestive systems, sleep and moods. “It’s very important to be exposed to light in the morning to reset the [body] clock,” Amir stresses. He adds: “Eating time is also very important. Food intake has a very strong effect on circadian clocks throughout the body.”

Athletes can control some factors, but not all. Sometimes there’s plain bad luck. Ironically, Brisson’s concussion happened during a selection camp six months before the Salt Lake City Olympics. Brisson was checked hard by another player, who then fell on top of her, slamming the back of her head into the ice, breaking her helmet.

The injury was a setback for Brisson, who found it challenging to deal with the long layoff. She followed a return-to-play protocol that progressed very slowly and with a lot of uncertainty. “When you’re lying on your friend’s deck in the middle of October, curled in the fetal position, trying not to vomit, you’re not even thinking about the Olympics, you’re just thinking about your health,” Brisson told the Toronto Star in 2002.

Mogul skier Alex Bilodeau works with a sports psychologist to improve his performance readiness and self-understanding.

Credit: Martin Girard

Mogul skier Alex Bilodeau works with a sports psychologist to improve his performance readiness and self-understanding.

Credit: Martin Girard

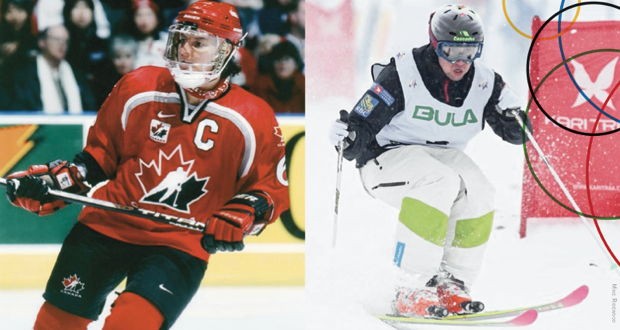

Gold medal winners Alex Bilodeau, right, and former concordia stinger Therese Brisson, who won with the 2002 Canadian women’s hockey team. The current squad features forward Caroline Ouellette, an assistant coach with the stingers, and assistant coach Lisa Jordan, BA 91; Julie Healy, BSc 83, is manager of team services for the Canadian Olympic committee.

Credit: Mike Ridewood

Gold medal winners Alex Bilodeau, right, and former concordia stinger Therese Brisson, who won with the 2002 Canadian women’s hockey team. The current squad features forward Caroline Ouellette, an assistant coach with the stingers, and assistant coach Lisa Jordan, BA 91; Julie Healy, BSc 83, is manager of team services for the Canadian Olympic committee.

Credit: Mike Ridewood

Geoff Dover, an exercise science professor, at Concordia’s PERFORM centre. The centre’s research includes looking at why some people feel more pain than others and how that affects recovery.

Credit: Concordia University

Geoff Dover, an exercise science professor, at Concordia’s PERFORM centre. The centre’s research includes looking at why some people feel more pain than others and how that affects recovery.

Credit: Concordia University