Richenda Grazette is the Lead, Community Leadership & Capacity at the SHIFT Centre for Social Transformation. She works to create innovative and accessible granting & support opportunities for socially transformative projects across Concordia and Montreal, while also coordinating and overseeing the health of SHIFT's shared power governance bodies. Before SHIFT, she had spent a decade in Montreal's nonprofit and philanthropic sectors.

"Bye Bye DEI": towards cultural overhaul instead of workshops

by Maureen Adegbidi and Richenda Grazette

Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library, via Flickr

Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library, via Flickr

In the last five years, institutional (including non-profit and philanthropic) trends in “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (and sometimes “Justice”) in Canada were largely focused on improving how marginalized peoples are brought into and retained at an organization. They feature workshops about hiring practices, what “power holders can learn” about working with diverse communities, how to take accountability, or task forces on decolonial thinking and writing better policies. These are all noble and valuable pursuits designed to create a better workplace and world, but when we take stock of what these DEI initiatives have actually accomplished since the late 2010s, what you’re confronted with is a fairly similar landscape, with perhaps slightly more diverse companies and institutions. However, those institutions still have untenable workloads, retention challenges, and dissatisfied employees. Concretely, how better off are we in comparison to before? How much have the core tenets of “equity and inclusivity” actually been achieved…and have we become diverse without substance?

Concretely, how better off are we in comparison to before? Have we become diverse without substance?

Now-common DEI initiatives slot more or less neatly into the normal operations of a company or institution, and therefore do not present the best route for meaningful change. In this article, we aim to critique these initiatives by approaching from an anti-capitalist and leftist perspective, arguing that now-classic DEI initiatives as not the best routes for meaningful change. Instead, we all must encourage our workplaces to engage with the material conditions of workers, living with the discomfort of substantial organizational restructuring, and having challenging conversations.

Don’t buy me a coffee: from grassroots movements to professionalization

Maureen: I recently came across a post on Instagram critiquing an emerging narrative online about the best way to “show up” for Palestine is to do “internal work” on oneself. The post also mentioned summer of 2020, “Black Lives Matter Summer”, and how what began as or felt like a constructive conversation about resource reallocation and police brutality was quickly and easily co-opted by the professional managerial class: instead of engaging with the systemic and material conditions of racialized workers (and thus their workers in general), institutions began a process of individualized self-flagellation.

I remember my frustration that summer with the individualized approach that people were taking to justice: I started getting block-text messages from friends and acquaintances apologizing for their perceived past racism or ignorance sharing promises to educate themselves. In some cases I appreciated the sentiment because it felt genuine and perhaps some reading and engagement was needed, but for the most part I was a bit exasperated. I have, for the vast majority of my life, been middle class, and I have enough understanding of my class position to realize that it protects me a great deal from experiencing the same things as people like George Floyd, or for an example closer to home, Nicholas Gibbs; both men from low-income or working-class backgrounds. This is not to say non-working class racialized people do not experience harmful instances of racism. We can and I have. It is to say that while I may have a particular attachment to or engagement with the issue of police brutality because I am a Black person, I am not the demographic most at-risk of this violence or most in-need. At the risk of sounding brash, it felt a bit like “ If you want to show people you feel bad about George Floyd’s murder, find the closest (middle class) Black person to apologize to”. I consider this 2020 dynamic analogous to contemporary DEI. Thousands of programs, workshops, talks, and zoom webinars have happened post the George Floyd moment. How many of these initiatives targeted issues faced by someone like him? And how many of them targeted (supposed) issues faced by someone like me? Even with this uptick in attention to white supremacy in what middle class institutions decided was white supremacist culture in this era, there was no actual change in a Black workers’ access to health days, higher wages, or to vacation, meaning the material conditions of the Black worker did not change. We know police brutality hasn’t disappeared either (in fact, in the US, it’s been increasing). When examined through that lens, what exactly was the point? This often-quoted line from Angela Davis continues to ring true:

“I have a hard time accepting diversity as a synonym for justice. Diversity is a corporate strategy. It’s a strategy designed to ensure that the institution functions in the same way that it functioned before, except now that you have some black faces and brown faces. It’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference.”

Policies aren’t enough

Take this article by Sherlyn Assam, recently published in The Philanthropist, citing research that shows hiring women into leadership positions might help with inclusivity, but does not fundamentally transform an organization. In the piece, Assam discusses how making changes to the way we work is more potentially impactful than simply who works in the organization or in leadership positions. Tokenistic hiring practices like these ones are still practices of convenience: it is convenient to hire a woman (especially a woman of colour) into a leadership position, and hope that her mere presence will usher in a new tomorrow. But policy and hiring practices alone are woefully inadequate and are - again - representative of the death of movement for the sake of neoliberal and professional class gain. As in, rather than working towards solidarity or changing work culture (and sometimes that means dealing with consequences of pushing against institutions), we prioritize the elevation of individuals into the existing structures of that institution as a “big enough step” in the anti-oppression direction.

Think about the diversity policies your institutional organization writes. Or think about the trainings, the “mission-speak”, the “toolboxes”, the many posters that litter the institutional landscape. As Sarah Ahmed explores in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, when the “document” (i.e., the toolbox, the policy) “becomes a fetish,” even the staff working on internal diversity become detached from it (p. 87). In these institutions, documents become a performance of inclusion, acting as a convenient substitute for action - an artefact of intention - rather than making real internal change. These documents also tend to remain unfinished or unimplemented, yet are still pulled out and referenced when questions about worker conditions are raised. It’s important to note that adherence to documents as the sole arbiter of whether something is “real” within an organizational culture, they reinforce white supremacy culture in the workplace. As the Centre for Community Organizations says, “worship of the written word” erases other forms of relations and knowledge, resulting in the organization missing out on valuable information and the hoarding or retention of power amongst a few individuals.

Richenda: I recently attended a talk with a large group of academics, where attendees shared their stories - or stories of racialized colleagues of theirs - who are forever asked to be on hiring or selection committees. Eventually many of them had to begin turning down those requests, not just for lack of capacity over time but also a growing disinterest and detachment from their own desire for change.

I find two problems here. The first being that constantly asking racialized peoples (and as an aside, when we talk about DEI it’s almost always focused on race and not the myriad other ways that a workplace can fail us) to do extra labour only reinforces the tokenism and extraction from racialized workers.

But importantly, the second problem is structural: the job description, the wages being offered, the hiring processes, and the sought-after candidate criteria – not just too-few racialized employees to distribute the work amongst. Fundamentally, white folks with a strong political and moral framing can and will hire racialized people if their workplace culture is open to difference. People will hire across class lines, if their organizations don’t require advanced degrees or good networks. Neurotypical or able-bodied people will hire those with disabilities or neurodivergences if their workplaces are adaptable.

In general, people will hire better if they slow their hiring processes down too. When they open themselves up to human-focused hiring practices, approach hiring from a desire to see every applicant succeed by providing resources and adaptations and have honest conversations about the real need they have in a position and what work they’re willing to do in training or “upskilling”.

But if a hiring committee is looking for someone who “fits” into a deeply white supremacy cultured workplace (i.e., someone who will work at the “right” pace, uses the “right” language, well networked, properly educated, conflict averse, etc) then they’ll hire for it – regardless of their intentions or what diversity policies they have.

The “document” trap isn’t exclusive to large institutions either; organizations and workplaces of all sizes and across sectors need a cultural overhaul. Take for example the community sector, known for alternative governance and “progressive” politics. Even in these nonprofit organizations, policies are written but the internal pressures and work issues remain the same: overwork, burnout, inequitable division of labour (often across gendered or racial lines). Although institutions are more likely to use empty and tokenistic approaches to DEI than grassroots organizations are (particularly given that those institutions steal concepts and approaches from grassroots), the fact that even with the most progressive politics they experience similar issues is testament to the reality that policy and intention are not effective tools for social justice.

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/RankPriv-handout.pdf

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/RankPriv-handout.pdf

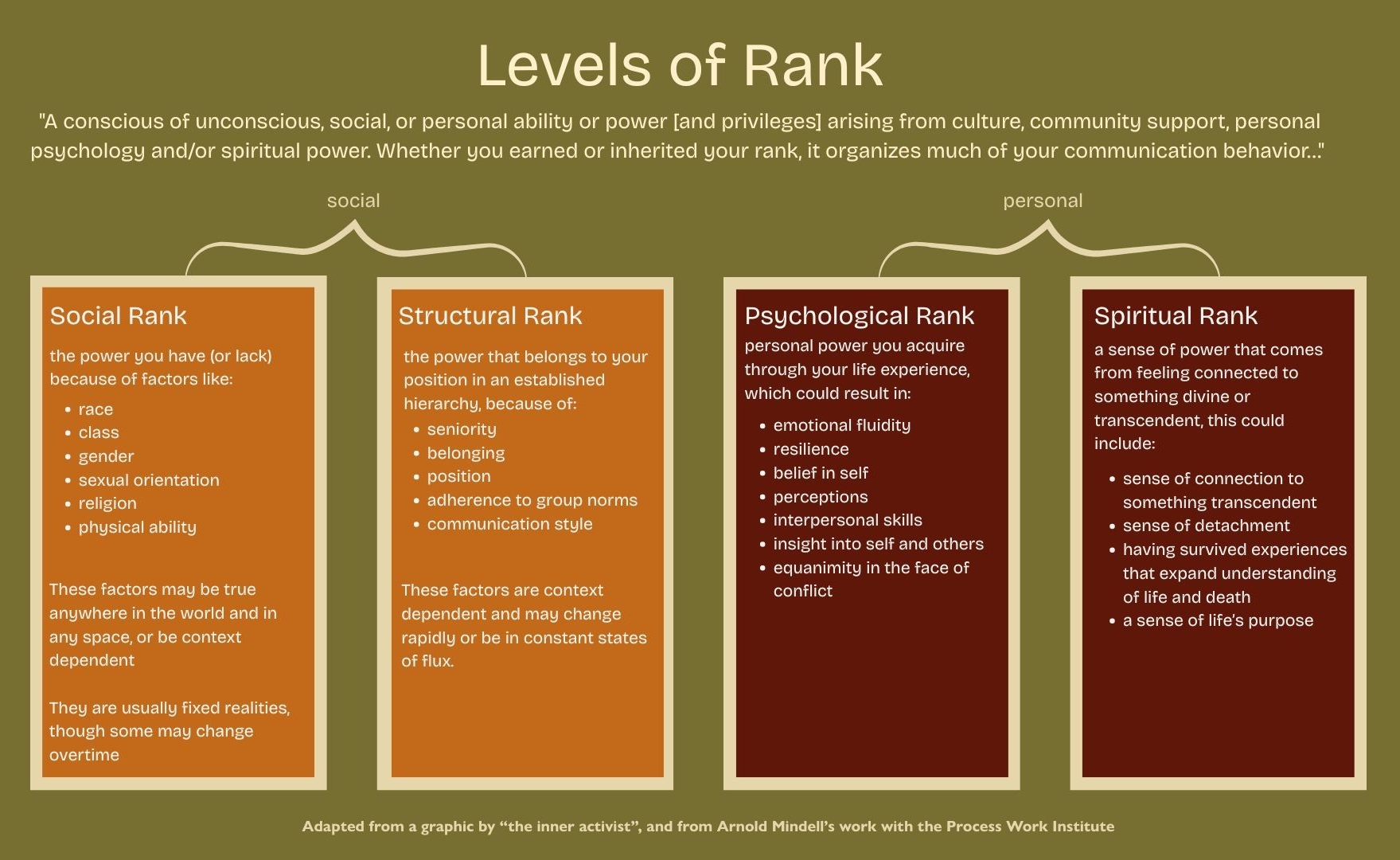

The DEI industry is also, largely, focused on “global power” structures: building trainings and tools that address all the kinds of power that come into the organization from the outside. While yes, the ways that these power dynamics and oppressions show up inside an organization, a near-exclusive focus on them obscures (or completely erases) the many other kinds of power that disrupt and reinforce oppressive or conflictual dynamics. As Delfina Vannucci and Richard Singer write in Come Hell or High Water: A Handbook on Collective Process Gone Awry, “It’s not ok to be against racism, sexism, and homophobia while being indifferent to the myriad other ways in which people are discriminatory toward one another or fail to understand one another’s perspective or experience” (63).

So, what’s to be done?

DEI efforts ramped up during a moment of acute crisis, and in crisis moments, we all search desperately for solutions. That may be why so many of us have made DEI into a catch-all fix-all convoluted space, practiced in many different ways by many different consultants and firms with varying qualifications and politics. This isn’t even to delve into issues regarding implementation, where companies often ignore structural change suggestions in favour of abstract, symbolic and aesthetic ones. The notion that DEI will save us “from the -isms” is a faulty one: it's too busy being subject to its own complicated industrial complex, but also simply because the problems facing workers, organizations and the world we live in are much too big for it to handle. DEI initiatives are one imperfect tool of many we currently have at our disposal to meaningfully respond to issues of inequity based on multiple factors within the workplace.

DEI is a tiny piece of a broader organizational culture puzzle that is constantly shifting and growing. While these puzzle pieces might often feel like the edge pieces (a potentially useful starting place), they still don’t put us anywhere near close to finishing the puzzle without that vast, amorphous middle. To treat it as anything more significant is a recipe for disappointment and frustration. Beyond that, a focus on DEI as the primary solution to systemic issues means neglecting serious local, grassroots, union, or other movements that have the power and potential to affect substantial material change in the places and spaces we work in.

DEI efforts ramped up during a moment of acute crisis, and in crisis moments, we all search desperately for solutions. That may be why so many of us have made DEI into a catch-all fix-all convoluted space

As much as we the authors fantasize about and want to see the collapse of capitalism, it is still the structure we live in right now. And under our system, in fact under many kinds of systems, work still has to happen. Even under alternate economic systems, someone still has to drive the buses. So writing a screed decrying DEI’s failings and advocating for smashed work systems without tangible and easily implemented changes serves no one in the near future.

In the next articles in this series, we’ll be proposing different things workplaces can implement that can begin internal cultural shifts without hiring a DEI consultant (or, maybe just hiring someone to help you get started). Of course, there is no overnight solution to oppressive organizational cultures: rather, we want to inspire workplaces to open up conversation and begin to think differently about their approaches and beliefs about what work can look like. We want to address not just the extrinsic benefits of work (i.e., paid time off for families of all kinds, higher wages, generous vacation and burnout policies), but the intrinsic benefits like growth, learning, connection, freedom of movement, and respect.

Our next article, Less Work, More Play (by Richenda) will explore the importance of (and some strategies for) implementing cultures of experimentation in the workplace.

Maureen Adegbidi is a non-profit worker and consultant based in Tiohtià:ke/ Montreal. She holds a Master’s degree from Trinity College Dublin in Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation. Her work in the non-profit sector has covered diverse subject matter, including human rights and anti-oppression education, access to justice and community safety, and most recently inceldom and radicalized misogyny ideologies. She currently works as a project manager and researcher at a gender based violence prevention organization.