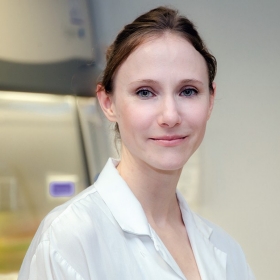

Sylvia Santosa, Canada Research Chair in Clinical Nutrition, and associate professor in the Department of Health, Kinesiology and Applied Physiology, leads a team of researchers at the centre’s Metabolism, Obesity, and Nutrition (MON) lab and is taking a cell-to-body approach to understand what makes someone with obesity more or less susceptible to metabolic disease and weight gain.

“We really want to know what it is about where fat tissue is stored in the body that might promote a greater risk of disease, as well as what affects those characteristics,” says Santosa.

The timing or duration of obesity may have something to do with the cells. “Understanding how our interindividual differences might affect our metabolism or fat tissue can potentially help promote more individualized treatment and treatment targets for the prevention of disease.”

Santosa’s team also conducts clinical research. One of her studies aims to determine how to set up better nutrition requirements for bariatric surgery patients — people who have parts of their stomach, and in some cases their intestines, removed to restrict the amount of food or calories they can ingest. The evidence on which postsurgery nutrition recommendations are based, Santosa explains, is minimal. “If we are able to understand the nutritional needs of individuals, then maybe it can help them in terms of recovery and weight maintenance post-surgery.”

Some of Santosa’s team’s findings to date support existing evidence that people living with obesity since childhood differ greatly from those who have developed it as adults. By understanding how tissue can promote or increase the risk of metabolic diseases, Santosa’s research will help develop better treatment for obesity, from disease prevention to nutrition management.

The Nutrition Suite at Concordia's PERFORM Centre.

The Nutrition Suite at Concordia's PERFORM Centre.

Sylvia Santosa

Sylvia Santosa

Kerri Delaney

Kerri Delaney

Jessica Murphy

Jessica Murphy

Théa Demmers

Théa Demmers