Concordia graduating student’s Indigenous video game wins a major prize

Maize Longboat had never made a video game before he came to Concordia. But now his first effort, Terra Nova, that he developed for his master’s thesis in Media Studies, has netted him a major prize.

Last month, Longboat won the award for Best Emerging Digital or Interactive Work at the imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival.

Available for download online, Terra Nova puts players in a first-contact situation that Longboat hopes will get them thinking about the significance of those interactions.

“These are really complex and important moments,” says Longboat, who’s graduating from Concordia this fall.

“They may have been pretty mundane, but it's the larger ripple effect that ends up building over time to where we get terrible things like cultural genocide, residential schools or disease.”

Can you tell us a bit more about the game?

ML: Terra Nova is set in the far, far distant future on an Earth world that's post post-apocalyptic. There has been a huge climate-change disaster, which forced a subset of humanity to leave and to attempt to colonize another planet.

But another group of humans had to stay, or chose to stay, and they essentially survived through this apocalypse. They changed, adapting their way of life to suit this new environment.

The game actually begins when the spaceship that left returns and the people that come back don't know that it's their original home.

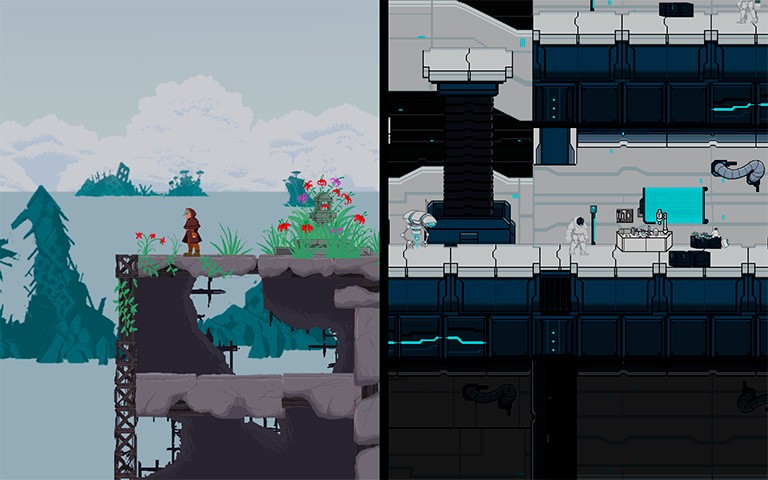

So the community that the character Terra belongs to, indigenous to Earth, witnesses this spaceship crashing, and she is sent to investigate the crash site. Meanwhile, Nova, a young colonizer, is separated from the starship in the crash and he's just trying to find his people again.

That’s when they come together.

They meet and soon realize they have to work together to help each other find the crashed starship and Nova's people.

That's the moment that it ends, with them looking over this vista of the smoking starship.

So the game ends with more of a question than an answer. Okay, this happened, this was a big moment, what happens next? I had more plans for where the narrative would go after that, but I thought it was more interesting to leave it open-ended and have players prescribe their values and what they would want to happen in the story after that moment.

What have people told you about the ending?

ML: I think they get it. You have to get there together to finish and I think they appreciate that. It shifts people's thinking about what's going to happen next when the two communities eventually have to interface and negotiate.

It's a two-player game and the screen is split. Terra, the character, is on one side, and Nova is on the other. When they come together the divide dissolves and it's one screen. That's the design lynchpin — they're separate and then they're together and that says so much about the playing experience.

It communicates so much without saying anything specifically.

The players can interact with people and objects in their environment, and choose specific options about how they want to respond.

Someone might ask you a question and you have to give them an answer and that might affect how you come away from that conversation. That's what the main first-contact scene is built on: how do I choose to respond to this totally alien person? How do I code that interaction?

What do you hope people take away from the game after playing it?

I wanted to really highlight the gray areas in which the Indigenous and settler perspectives overlap — trying to demystify the us-versus-them binary and show that it’s more complicated than that.

I didn’t make the game for anybody specifically. I just wanted to make something that I could relate to as someone who has mixed ancestry.

My dad is Mohawk from Six Nations of the Grand River and my mother is French-Canadian from here in Montreal. I see myself represented in the game from both perspectives. I felt like I could really speak to that strongly when developing the narrative and developing the game. That's what I wanted to show to other people too, not just the theoretical side of things, but also a piece of myself.

What did you discover through the process of making Terra Nova?

ML: What I wanted to explore primarily through making the game was an Indigenous experience. Being in communication studies, I thought that looking at first-contact scenarios between Indigenous people and settlers could both show the experience from the perspective of an Indigenous person in a game format and also have that communication element.

The decision to frame it in the future was also important. I felt like there were a lot of possibilities when setting the narrative in a timeline that I could imagine, and dream up.

I took a lot of inspiration from history and first-contact scenarios in Montreal and (Tiohtià:ke) when Cartier came. I read what happened when he met my people, the Mohawk people, here.

I'm constantly coming up against first-contact narratives, either portrayed through Indigenous oral histories that are then recorded and written down, or through the eyes of white settler explorers, mostly men.

What made you decide you wanted to make a video game?

I was born in 1994, so games have been a part of pop culture my entire life. During my undergrad I was exposed to Indigenous digital media — games, websites, web apps, etc. I had never made a game before, but I was interested in incorporating making and practice-based learning into my graduate education.

Communication studies, specifically the media studies program, has a research-creation thesis option. I thought that would be a really good fit. I didn't do a fine arts degree for my undergrad. I was much more comfortable writing and researching than actually making something. But I wanted to change it up for my graduate degree and put myself out there a little bit.

I couldn't have done it this way — making a game that I could then put online for anyone to play — unless I had a lot of help. First of all, I got a research grant from Hexagram, which is Concordia-affiliated, and then also, the MA level award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). I used money from that award to pay three other team members to help make this game. I didn’t just make it on my own, but it was my vision and my resources that made it happen. I’m so thankful for the contributions of my team members: Ray Caplin, the game’s artist and animator, Mehrdad Dehdashti, the technical director, and Beatrix Moersch, the sound designer.

You won the award for Best Emerging Digital or Interactive work at the imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival. What was that like?

That was a wonderful, incredible surprise. I was encouraged to submit the game to the festival, because I had been to it last year and I had seen really amazing digital works, games, VR made by other Indigenous producers.

I was really able to see the possibility of what an end product could be. It was definitely a goal throughout the production process to get something that I was proud of enough to submit. Luckily we got there and it got in.

Everything that gets into the festival is considered for an award. I knew that going into the week, but as things kept going and building and more people got to see the game, I started to feel that there was a possibility it could win.

When my name was called and Terra Nova was selected it was definitely a huge honour and a big surprise. It's the biggest indigenous film and media festival in the world! So to get that recognition from other Indigenous people is really meaningful for me and members of my team.

It makes me want to continue making games and makes me feel people believe in me.

What influenced your decision to come to Concordia?

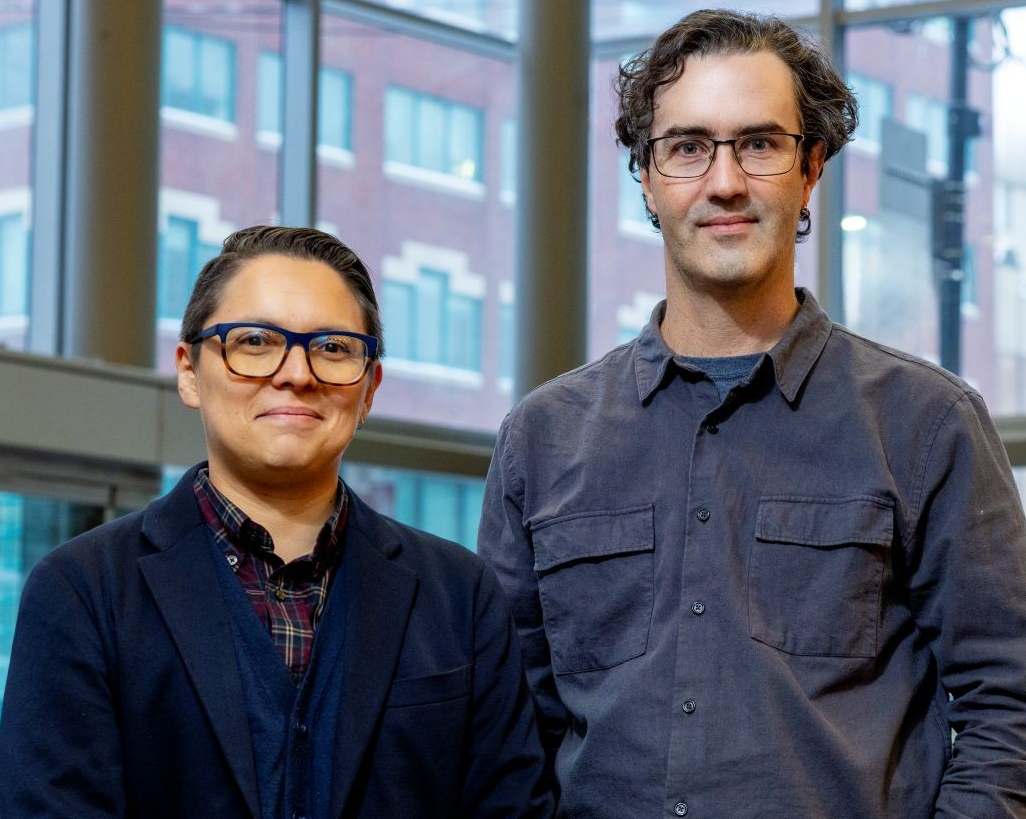

I grew up in the Vancouver area and did my undergrad at the University of British Columbia. I had a professor named David Gaertner, who taught a course focused on Indigenous digital media. He recommended that I look into Concordia and the work that Jason Edward Lewis and Skawenatti were doing with Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTec), and the Initiative for Indigenous Futures (IIF).

Their research was definitely the main pull to come to Concordia, and deciding to do my master’s in communication studies was a good way to get my foot in the door — to be here, to study and work on a project that I was excited about doing, while working alongside them.

I was a research assistant with them for the past few years and I've just recently been hired on full-time as the associate director for the Skins workshops on Aboriginal Storytelling and Digital Media.

The best part about working with them all these past years was helping to support the Skins workshops. They saw me as someone who could help develop the workshops further, so I'm excited to get started on that.

Do you have any other plans after graduating?

My plan is to continue supporting Indigenous game development. There’s a whole Indigenous game development community that I've felt welcomed into with open arms. It has been really inspiring to have people that I've not only gotten to know through my studies and through the games that they have made, but as people as well, through making my own game. I'm really committed to supporting that work.

Find out more about the Department of Communication Studies and the Department of Design and Computation Arts.