Genitalia in the animal kingdom

Meanwhile we may feel inadequate about our genitalia, other animals enjoy their variety of penises and vaginas. From three-headed penises to vaginas with ‘pockets’, the variety of male and female genitalia in the animal kingdom is beyond comparison.

Evolution works by reproduction. Thus, any a slight variation or improvement in genitalia can make the difference between the animals who pass along their genes and the ones who don’t. So, what is the point of such decorative variation among species? After all, the function of genitalia appears straightforward. A penis deposits the sperm, and the vagina receives and delivers it to the egg. From an anthropocentric perspective, a phallic-like penis and a funnel-like vagina would do just fine. Yet, it is not what we see in reality. Throughout the animal kingdom, genitalia are much more complex organs, for their role go far from just simply deposit or receive a seed.

Every time a new animal is born, slight variations from the genes are selected by nature creating a unique individual. Thus, no penis or vaginas are the same. These variations are the ones that may post an advantage to others to ultimately pass along their genes. For example, penises have evolved to be part of the whole courtership. Male crane flights have a vibrator-like ‘adornment’ which produces a song that reverberates throughout the female’s body when they mate. If the female likes what she hears, she would allow the male to father their offspring. Similarly, some beetles have ‘drumsticks’ on the side of their penis that during mating rub, tap, or spank the female. On the opposite end, female genitalia have evolved to be able to select which male sperm they will bear. For instance, dung flies vaginas are equipped with “pockets” that contain the sperm of different males depending on how appealing they were. Moreover, female chickens eject more sperm after mating with a ‘low-ranking’ male than she mates with a ‘high-ranking’ male.

This furious evolutionary tango of reproduction between penises and vaginas has lead to even more interesting adaptative strategies between males and females to (re)gain control. Male widow spider posses a ‘detachable’ penis tip that remains inside of the vagina after insemination to block the sperm of other competitors. Male rat sperm, for instance, forms a plug that also serves the same purpose. Yet, female vaginas do not remain behind. When a female ducks do not want the long, coil-like penis of the male counterpart, all she has to do is to flex her vagina muscles that will ultimately expel the duck’s penis.

Little has been said or studied in this matter on humans. Most of what is available are hypothesis and speculations. It is believe, for example, that male human semen may be able to induce ovulation in women. Researches also speculate about orgasm and its role in female selection, claiming that the involuntary contractions experienced during orgasm may serve as a ‘sucking’ mechanism to assist insemination. As the evolved specie we are, humans use other strategies to ensure their genes pass to the next generations. For instance, mate guarding tactics help a selection based on partner’s fidelity. A similar strategy that believed to be triggered by environmental adaptation in other animals, like rats.

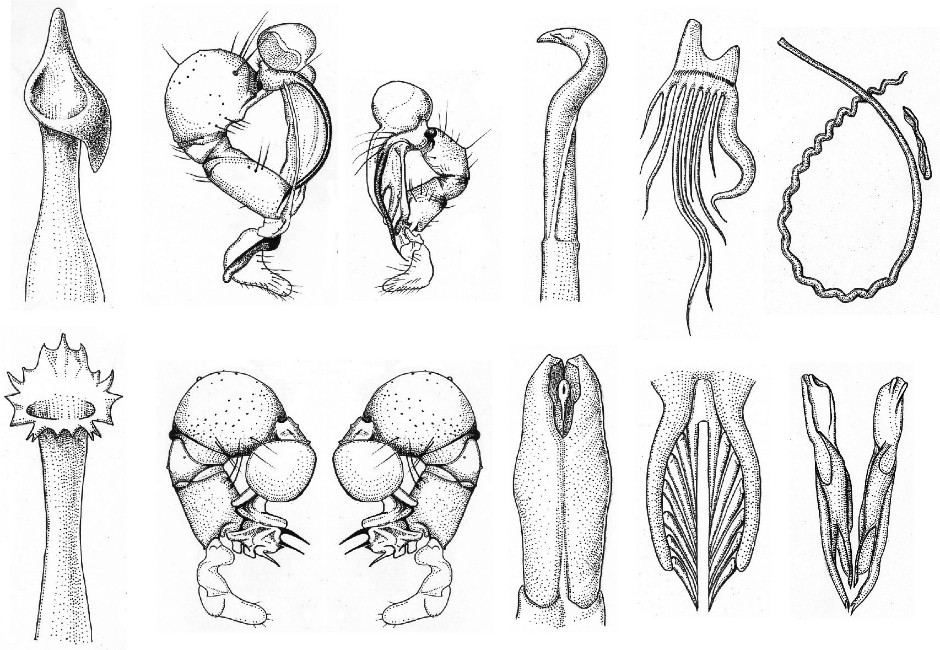

drawings of different male penises in the animal kingdom

drawings of different male penises in the animal kingdom