Naghmeh Bandari received her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in biomedical engineering from Amirkabir University of Tehran, Iran, where she served as a Certified Medical Device Technical Supervisor for six years. She is a doctoral candidate of Mechanical Engineering at the Optical-Bio-MEMS and Robotic Surgery Labs. She is also a fellow of Surgical Innovation at the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) CREATE program for Innovation-at-the-Cutting-Edge (ICE). Her research focuses on the development of optical tactile sensors and micro-optical mechanical systems for robotic and surgical applications.

Blog post

The da Vinci robotic surgery system lives up to its name

Photo courtesy of Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Photo courtesy of Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Would you feel worried about a robot performing surgery on you? What if you realized that it could help the surgeon perform your surgery safer, faster and more precise than before?

In October 2010, 68-year-old Gilles Lefort had his prostate removed by two robots — da Vinci and McSleepy. This was the world’s first all-robotic surgery, which happened at the McGill University Health Centre. Lefort recalled “waking up in the operating room with no nausea and with a sharp mind.”

“It’s a good technology,” he stated. On that historic day, surgeons used McSleepy to put Lefort under anesthesia while operating on him using a da Vinci robot.

In the year 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared Intuitive Surgical’s first robotic surgery system, da Vinci, for general surgery. Since then, surgeons have successfully used it on more than 775,000 patients all around the world. It is important to note that surgical robots like da Vinci are controlled by a surgeon, similar to how you control a player in a video game.

Technologists have enhanced robotic surgery on two fronts. The first has been improving a robot’s sensory capabilities. With this, robots can have a better understanding of the patient’s conditions during surgery. The second front has been modifying surgeons’ interface with the robots. This means surgeons have less hassle when controlling the robot.

A study at the Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates showed that robots ameliorated surgery for both patients and surgeons. For example, robotic surgery has reduced blood loss, trauma, infection, recovery duration, hospitalization time and X-ray exposure. It also improved the accuracy, dexterity and precise control of surgical instruments.

It is well-documented that for long runs, a robot holds instruments much steadier than the surgeon’s hand. Natural hand tremors and fatigue shivers are inevitable after long hours of surgery.

At the same time, the use of a robotic arm as a liaison between surgeon and patient has its limitations. Robots are expensive, it is hard to keep them sterile and, like any other computer system, they are prone to crash and glitch. Also, surgeons have identified the loss of direct palpation as the primary limitation of these robots.

Surgeons use their senses of touch and vision to identify different organs in surgery. Without either of these, the risk of misdiagnosis or malpractice is high. Studies have shown that without direct touch, surgeons tend to apply excessive compression on organs. Excessive force might lead to permanent damage to an organ.

However, this should not undermine researchers’ efforts toward more intelligent surgical robots. Recently, researchers at Concordia have developed optical tactile sensors for robots, which enables surgeons to feel as they would during manual surgery. It is like virtually extending the surgeon’s fingers through the robot inside the patient’s body. Cutting, sewing, grasping and instrument control in robotic surgery has Improved significantly since Gilles’ 2010 surgery.

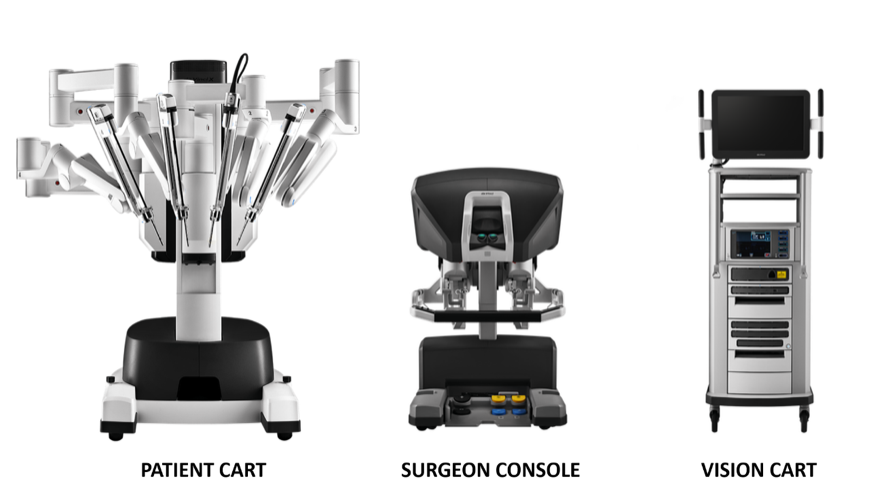

Three components that make up the da Vinci system | Photo courtesy of Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Three components that make up the da Vinci system | Photo courtesy of Intuitive Surgical Inc.

So, the takeaway here is that we shouldn’t be so afraid of robotic surgery, which holds great promise for safer, faster, cheaper and more accessible surgical care. Despite the implications on social media and the news, fully autonomous robotic surgery is a myth.

During the last few years, a hot debate has been going on between technologists and ethics activists. Technologists push for more autonomy for robots, while ethics activists advocate for human treatment in patients’ rights. Technologists point to enhanced safety, as well as less time and trauma in robotic surgery, while ethics activists raise valid concerns on the limited ability of robots on risk prevention.

To date, there is not enough clinical evidence to dismiss either argument.

For the foreseeable future, ethical and clinical considerations will ensure surgeons remains involved. However, technological advancements will make robotic systems more intelligent and tamer. Nevertheless, with increased artificial intelligence advancements, more ethical concerns will be resolved in the coming years. Thus, hopes are high that in the near future, da Vinci will assist doctors in people’s surgery with the same finesse as the great da Vinci drew the Mona Lisa.

About the author