Michelle Savard is a doctoral student in Education. Keenly interested in peace education and child protection, her research examines both the marginalization and the reintegration of formerly abducted young mothers in Northern Uganda. She has more than 20 years of experience designing, delivering and managing educational programs both nationally and internationally, which includes training for educators, police peacekeepers and social workers. She has co-edited a prestigious journal and coordinated the delivery of international conferences.

Blog post

From civil servant to advocate

Women engaged in a workshop in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Allie Theorcharides

Women engaged in a workshop in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Allie Theorcharides

Think about these numbers: there are more than 300,000 children who are currently active in armed groups for military organizations, militias and rebel groups in at least 86 countries. Approximately 120,000 are girls and young women. Learning this changed the trajectory of my life.

What fired me up

While working in a comfortable job as a learning specialist for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), I created a two-year learning strategy for police peacekeepers deploying on United Nations (UN) missions. While on this project, the RCMP was invited by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations for a one-week conference in Accra, Ghana to provide feedback on their pre-deployment training. I was chosen to participate.

I did not know much about western Africa but I did know that Ghana had been a principle source of slaves for the “new world,” and had been colonized and brutalized by the Portuguese, Danes and British for more than 300 years until they achieved independence in 1957.

As I explored Accra — so aware of my whiteness — I was met with soft gazes, warmth and kindness. I developed a relationship with a vendor on the beach. Each night after the conference, I would seek him out and we had many enriching conversations. At one point I asked him, “Why don’t you hate me?” How is it possible that a people so persecuted by whites could appear so warm, hospitable and welcoming?

I never forgot his answer. He said, “There is no freedom in hate.” In other words, it is my race that is in shackles. This is particularly true now if I consider the current rise of hate speech, hate crimes and racism in Canada.

The training analysis revealed that peacekeepers needed to learn about potential encounters with child soldiers. I learned that these children are largely abducted from their homes, communities and refugee camps, and participate in active combat and/or they provide support functions such as domestics, servants, porters, bodyguards, drug mules, “bush wives” and the like.

When these children are liberated or escape from rebel or government forces and return home, they are marginalized by their communities. Specifically, girls are stigmatized for having had children out of wedlock as it violates cultural norms. However, some get access to reintegration programming which provide vocational training, counselling and outreach to communities to foster acceptance of returnees.

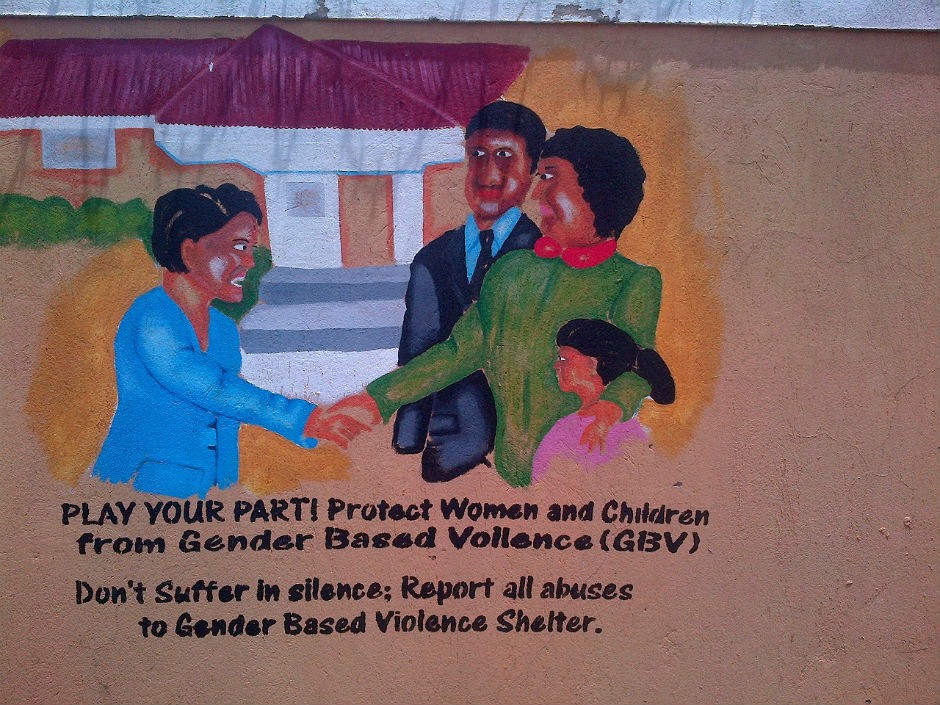

Painting on a building in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Michelle Savard

Painting on a building in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Michelle Savard

Focussing on Uganda

It was when I started focussing on children who had been abducted during the civil war in Uganda (1986-2007) that I learned that reintegration programs have little long term impact. Programs use “ad-hoc” and deficit-based approaches treating former abductees as broken people that need to be fixed and furthermore, they rarely conducted program evaluations.

Specifically, for girls and women, these programs do not meet their needs and they do not address patriarchal values that keep women marginalized and living in poverty. This is concerning as there is enough research demonstrating that when reintegration is not effective, youth tend to re-join rebel groups which poses a threat both nationally and internationally.

There is no single explanation as to why I felt so connected to the plight of these women and had such a compulsion to “do something.” Ordinarily I would have simply thrown money at the cause or click “I agree” in response to a poll: “Should child soldiering be eradicated?” But the need I felt to do something was unbearable.

Perhaps I hit a stage in my own personal development where the time had come for me to take my head out of the sand, develop a social conscience and take responsibility for how colonialism and my white race had contributed to the plight of these women and children.

Whatever the reason, ultimately, I do believe that caring and concern extend beyond rationality and comes from a connection we share with all humanity which makes us inseparable from other beings.

Workshop on marginalization in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Allie Theorcharides

Workshop on marginalization in Gulu, Uganda. | Photo: Allie Theorcharides

Little did I know...

I started with the belief that my background in program design would allow me to evaluate reintegration programs, find the gaps, create a new model for reintegration and all that I lacked was an understanding of the context and what works in the field.

I knew nothing about how the barriers to reintegration operate at every layer of Ugandan society starting with limited “real” support for reintegration from the national government; and followed by scarcity of resources for single mothers; lack of advocacy for single mothers and their children; and the pervasive notion that women are considered property.

Nonetheless, for the next five years, I would find myself immersed in the literature; engrossed in some of the most profound relationships I have had in my life; in and out of northern Uganda; sitting in huts on packed mud floors in sweltering heat, choked by dust; and listening to stories that both broke my heart and lifted by soul.

First computer workshop graduating class. | Photo: Susan Ajok

First computer workshop graduating class. | Photo: Susan Ajok

The research

My research examined three approaches to the reintegration of war-affected and formerly abducted young mothers in northern Uganda; and compared each program, after two years, on how well it enhanced well-being, financial stability and social inclusion. To frame this comparison, and to challenge how international development actors create spaces for reintegration, I used the theory of social spaces put forward by Cornwall and Coelho (2007).

The first approach I investigated were “formal or closed spaces,” namely two reintegration programs headed by non-governmental organizations.

The second approach was a space created by 20 young mothers, community members, elders and I where we adopted Home Depot’s motto, “You can do it, we can help” and supported the women in achieving what they determined they needed. The approach was strength-based, participatory and group-directed.

The third space was “claimed” by a local group of women who got together once a week, saved money as a group and borrowed from the group for small business loans.

In the end, I found that most of the women who graduated from the formal reintegration program were not working in their fields because they were all trained in gendered trades for markets that were already saturated.

The women in the claimed space had established a powerful social network and small businesses but the group I worked with made the most advances so I asked them to explain why. Some of the women said, that they had found “love” and a “voice” in this group.

These women are so strong, resilient and determined but they do need advocacy, a hand up and to know that we care.

About the author