Ghost of Griffintown

In 1879, a decapitated female body was found in a house in the Montreal neighbourhood of Griffintown. The body belonged to Mary Gallagher, a local woman who was somewhat notorious for drinking and keeping company with many men. The gruesome tale caused a media sensation, and Susan Kennedy was swiftly convicted of the crime.

Gallagher’s story became a cautionary tale warning young children away from drink, and continues to (literally) haunt the public consciousness because legend has it that she returns to the scene of the crime every seven years to retrieve her head. (She’s due to appear next in 2012).

A grisly, dramatic, local ghost story would capture any imagination, but Alison Loader was especially drawn to the story. She teaches animation in Concordia’s Department of Design and Computation Arts and the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema while completing an MA in communication studies.

“I was really fascinated by Griffintown, and of course Mary Gallagher is the first thing you find. People love a good mystery.” Loader’s research on old and new media and 19th-century representation and visual culture made the story a perfect subject for her to tackle.

“I’m interested in how Susan Kennedy has been represented,” explains Loader, who describes how Kennedy obsessively scrubbed the floor with a scrap of Gallagher’s lace after the murder. “She’s loud, drunk and disorderly, but there’s no indication she was a prostitute, she’s just always depicted that way,” says Loader. “If people talk about her at all now, it’s only as a monster. I’m not 100 per cent sure she was guilty.”

This June 4 and 5, Loader will present Ghosts in the Machine: The Inquest of Mary Gallagher, her multiple-perspective retelling of the story. The site-specific work will be displayed in the former police station, now a rehearsal and carpentry shop for Centaur Theatre. Ghosts developed when Concordia PhD candidate Shauna Janssen approached Loader to participate in Urban Occupations, her program of art interventions in Griffintown. Loader was happy to apply her reflections on the relationship between storyteller and audience to Gallagher’s tale.

The construction of the video/sound project started with journalist Alan Hustak’s book The Ghost of Griffintown: The True Story of the Murder of Mary Gallagher and interviews with local historians.

“I would ask where they got the information and it was always back to the newspapers,” says Loader. In the 1870s, there were four English dailies. Updates and details of the inquest, which were published verbatim in most papers, were printed in multiple editions throughout the day. “The experts all use the same articles. It’s not really oral history, but they share the same sources.”

Going through the articles herself, Loader was surprised by the frankness of the descriptions. “It’s just like CSI.” Some papers published graphic accounts of the state of Gallagher’s corpse. The press also revealed how people rushed to the crime scene and to the courthouse. “Hundreds of people saw the body: Police let everyone in to the crime scene,” says Loader. A female murder suspect upped the excitement and interest in the case.

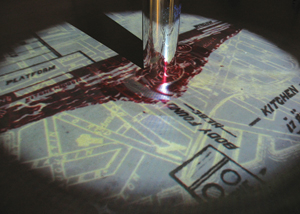

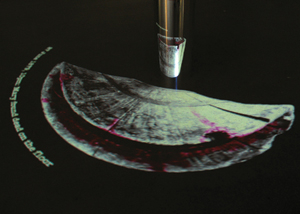

Loader’s retelling of the story relies on news accounts, maps, silhouetted figures and six local actors who volunteered to perform text from the inquest. The scenes are projected onto the floor in three sets of images that incorporate different outcomes for the inquest (guilty, innocent or mad). The anamorphic, distorted films appear in proper perspective only when reflected back onto shiny pillars in the centre of each projection. When audience members move through the space, they will see one thing on the ground and its reflection in the pillar, and have a different perspective on the situation depending on what they choose to pay attention to and how they move through the space.

Loader likes this kind of interactive production. It was a desire to interact (and to teach) that led her to leave her career at the National Film Board and return to Concordia (she had earned a BFA here in the 1990s). “I’m a filmmaker who got tired of sitting in theatres.” She began teaching part-time in 2001 and eventually decided to pursue an MA. Loader is set to start a PhD in communication studies in the fall.

Loader sees echoes of the multi-edition press that covered Gallagher’s murder in modern social media such as Twitter, and there are other combinations of old and new in Ghosts in the Machine. Although the anamorphic projections seem extremely avant-garde, they are adaptations of 15th-century technology. And the piece itself employs images from and inspired by the work of Eadweard Muybridge, who was experimenting with photography and the birth of cinema at around the time of the inquest. Muybridge was also exonerated of the murder of his wife’s lover during his lifetime. “He’s a killer who gets away with murder. It raises questions about who is found guilty and who isn’t,” says Loader.

Related links:

• Concordia's Department of Design and Computation Arts

• Concordia's Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema

• Concordia's Department of Communication Studies

• Ghosts in the Machine

• Alison Loader