This class is unreal!

“This is the best movie ever,” says Electrical and Computer Engineering professor Nawwaf Kharma as he holds up a copy of the 1982 sci-fi classic Blade Runner. His opinion is based on the character of the elderly geneticist, Hannibal Chew, who can create artificial eyes.

While the idea might seem fantastic, for Kharma, it’s not science fiction.

“In the future, we’ll be able to biologically engineer entire custom-made organs in a lab. Just watch.”

The 25 students in his Biological Computing and Synthetic Biology class this term might be the ones to do it.

The first Quebec course in synthetic biology, COEN 691A/BIOL 498S is a collaborative effort between Kharma and Biology professor Luc Varin. The course is open to both undergraduate and graduate students studying either biology or electrical and computer engineering.

“This course is about bridging engineering and biology and designing computational machines that can be implemented in biological media, such as cells,” says Kharma.

For the less scientifically inclined, the term ‘computational machines’ might be a bit misleading; it doesn’t mean tiny hardware gadgets placed in cells. Rather, they are exploring ways to “rewire” the cell’s genome.

The modified genome contains a gene regulatory network, or GRN: a group of genes that create, in essence, a circuit with a computational functionality – this means the cell or cells can be programmed to produce a desired effect or chemical.

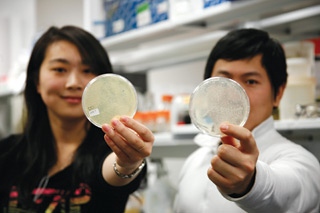

As an example, Kharma describes a GRN that was built for a specific bacteria by students. When the bacteria were placed in water with arsenic they displayed a green fluorescence, signifying poisonous levels of the toxin. “This was made by a team of mostly undergraduates in less than a year in a lab just like this one,” he says.

The GRNs can be designed for a range of uses from sensing environmental changes to drug delivery in humans. Students won’t be formally creating a GRN in the class. Instead, after separate three-week crash courses in which biology students study engineering and vice versa, they will work in teams of three to develop a proposal for a GRN design.

“It’s very cool because engineers look at it from the information processing point of view, and biologists think more about the expression of genes,” says Yao Zhang, a biology graduate student taking the class. “I am learning a lot from the engineering side.”

Kharma and Varin designed the class to point the students to a novel scientific field that is rapidly evolving.

“What this class does is introduce this field to the new generation of students and researchers. People in synthetic biology plan projects that are as visionary and eccentric as possible,” says Kharma.

How visionary? How about the production of programmed cells that will be able to accurately seek and destroy harmful cells, such as cancer? It’s a treatment he believes will exist in less than five years.

Blade Runner isn’t required viewing for the class, but “it’s still very good,” laughs Kharma.

Related links:

• Concordia Department of Biology

• Concordia Faculty of Engineering and Computer Science

• Luc Varin’s home page

• Nawwaf Kharma’s home page

• International Genetic Engineered Machine (iGEM) Competition