Laura Shine is a doctoral candidate in Concordia’s Humanities program, in the fields of food anthropology, food marketing and sensory studies. She investigates the changes in attitudes and behaviours towards novel foods, with a particular focus on entomophagy. She has served as strategic consultant on the board of insect start-ups and presented talks and workshops on eating bugs in schools and university settings. In 2017, she devised and taught an undergraduate course in Food and Culture in Concordia’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Her research has been supported by scholarships from the SSHRC and the FQRSC, and by a fellowship from the Luc Beauregard Centre of Excellence in Communications Research.

Blog post

Finding our voice

It’s been an interesting year as a Concordia public scholar.

When the university chose me to embark on this journey, I joined a cohort of nine other scholars from diverse fields. All of us shared two common beliefs — that research matters, and that it’s worth sharing.

We found some challenges along the way, too; translating years of reading, writing and thinking about a specific topic into a single sentence or a few punch lines sure is daunting, but can also feel reductive. Where to draw the line between communicating engaging research and oversimplifying for the sake of a “memorable quote?” Can scholars communicate all types of research in similar ways? How to frame research when its public utility is not self-evident?

I’m afraid to report that we found no one-size-fits-all answers to these questions. Thinking about such issues is a work in progress, and one that every scholar faces at some point in their career. But when that time comes, having the right tools to talk about your work helps.

The Public Scholars program provided me with training to do just this: how to communicate research in meaningful and impactful ways, how to interact with various audiences, how to share findings with a wide public and how to show that they should care about them too. In other words, how to engage with the world outside the university’s walls.

Getting engaged

One of the workshops offered had a particularly important impact on my own trajectory. Shari Graydon, the founder of the non-profit Informed Opinions, delivered a two-part course in writing op-ed pieces for newspapers.

Though she occasionally dispenses mixed workshops such as the one we attended, Graydon’s work deals almost exclusively with amplifying women’s voices in the media and training female experts — with a wide definition of expertise — to share their knowledge and occupy more space in the public sphere.

Inspired by her ideas and engagement, I endeavoured to join the organization as a volunteer and eventually became a full-fledged member. My colleague Maïka Sondarjee and I took on a specific mandate: to bring Informed Opinions’ message and method to a francophone audience, and to engage and inspire francophone women throughout the country to share their knowledge, ideas and opinions with a wider audience.

And with this ideal in mind, Femmes Expertes was born.

Like its umbrella organization, Femmes Expertes has a triple mandate: a) advocate for a more equitable representation of women in the media; b) manage a database of female experts who are willing to share their knowledge with the greater public, a tool to easily locate a specialist in any field; c) offer mentorship, training and support to women who want to engage with the media.

We are committed to promoting both a vast definition of expertise and an intersectional approach to the diversity of voices that we help amplify.

Is this actually an issue?

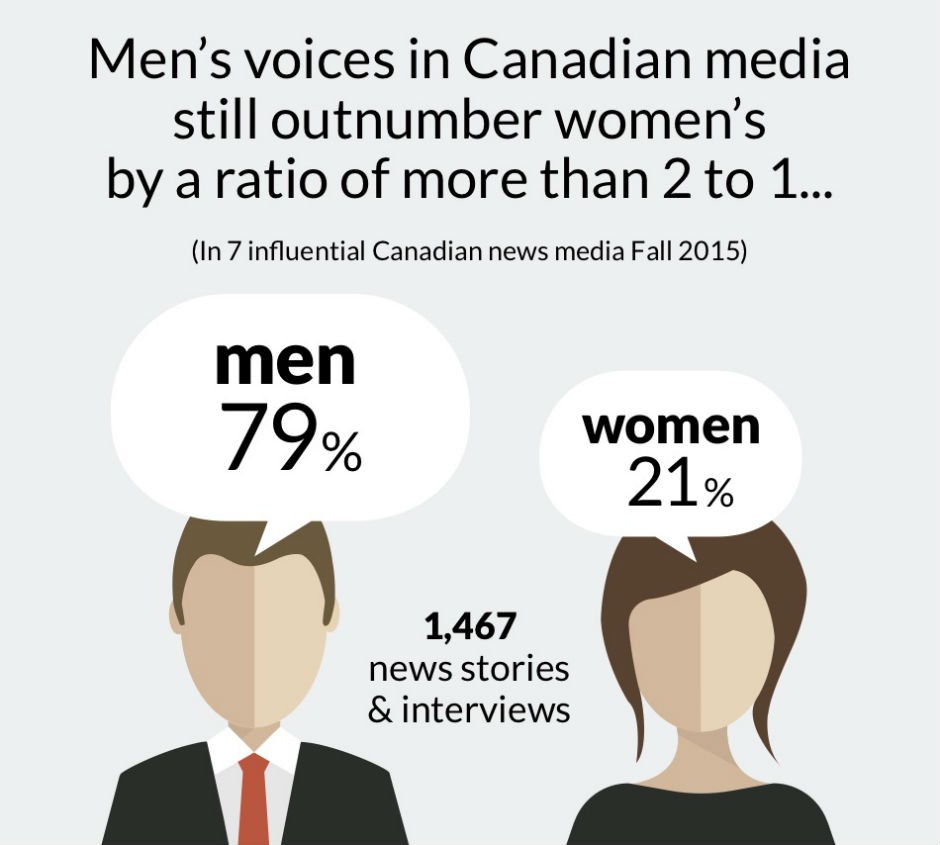

In the Canadian media landscape, male experts still outnumber women more than two to one. This average takes into account professional fields such as healthcare and education, which comprise many more women than men. The ideal expert model remains ever the same; authority seems to be the purview of middle-aged white males.

Why should we care? And why is representation important, anyway?

In a recent essay (1) examining women's and minorities’ political underrepresentation in Quebec, Myriam Bernet outlines three types of representation in the public sphere and their importance for society at large.

1. Descriptive representation takes into consideration the “characteristics of individuals rather than their actions” and thus refers to the statistical side of things. Numbers should balance out to portray social composition more accurately, for reasons of equality and justice.

This is why, in the case of women’s representation in the media, we use the notion of parity; since roughly half of the population is made up of women, the voices we hear when we tune in or read when we open the paper should reflect this. A finer slicing and dicing can evaluate the prevalence of women in specific fields of expertise, for instance, and compare this to their presence in media outlets.

Research commissioned in 2015 by Informed Opinions did just that, and found a significant statistical discrepancy in all fields it examined. Strikingly, for example, while women make up 80 per cent of health-related occupations in Canada, they only accounted for 45 per cent of experts quoted in the sources examined in the study.

Many media outlets make a big deal of accurately representing the public they serve, yet the diversity of the sources they call upon hardly reflects this ideal.

2. Substantive representation, on the other hand, refers to what people do, rather than their characteristics. In the political field, this can mean examining the types of policies put forward by female legislators, for instance to better the conditions of women in general. In the field of media, it refers to the types of ideas, expertise and opinions expressed by women.

When Informed Opinions created word clouds out of men’s and women’s op-eds and compared them to create a third cloud with themes only discussed by women, they found words as diverse and important as safety, equality, assault, diversity, female, violence, water, racism, food, child, girls and sexual. There are expert women in all fields of knowledge, including in ones that lie outside of the purview of institutional sanctioning.

We must ensure that we hear and heed these diverse voices. Equality of representation goes far beyond statistical justice; it ensures that women’s beliefs, knowledge and preoccupations are accurately depicted and communicated. And that benefits everyone.

3. Finally, symbolic representation refers to the type of impact that representation can have on the general population, or the audience in the case of media outlets. The idea behind this is that seeing a woman — or a person of colour, or a member of any marginalized group — in a position of expertise, sharing their knowledge about a specific issue, can model expectations and behaviours.

Seeing women astronauts or detectives on television can inspire and empower young girls to venture into less traditional fields; it reminds all watchers that expertise is not defined by gender, or by other types of characteristics that serve to marginalize social groups.

What can we do about this?

For all these reasons and many more, our driving commitment at Femmes Expertes and Informed Opinions is to achieve gender balance in the Canadian media by 2025. With our triple focus on advocacy, expert database tools and training, we are getting more women on the news and in the papers.

Some media outlets, especially the CBC and Radio-Canada, have implemented strategic mandates that include this objective and are making strides. Others have a lot more work to do before they can claim to accurately represent the audience they claim to serve.

As a society, if we wish for more justice and fairer representation, it is our responsibility, collectively, to demand more of our media, and to contribute what we can to achieve a more balanced outlook. As a woman, a public scholar and the co-lead of Femmes Expertes, I now know what role I have to play. What about you?

(1) Bernet, Myriam. “Exclusion des femmes et des minorités invisibles dans le champ politique québécois”.In Coll. 2018. Paroles de femmes, inclusions politiques. L’Esprit Libre, 31-45.

About the author