Les caractéristiques et enjeux du JHA

Fact sheets

Consult the Fact sheets and virtual paper prepared by the Research Chair on Gambling.

Consult the pdf version of this factsheet here.

GAMBLING TRAJECTORIES IN QUÉBEC

The last two population surveys on gambling conducted in Québec in 2009 and 2012 revealed that the prevalence of gambling participation in the province decreased but the proportion of problem gambling* remained stable[1]. Still, little is known about the transitory nature and chronicity of gambling problems and how they emerge, evolve and eventually attenuate over time.

Gambling Trajectories

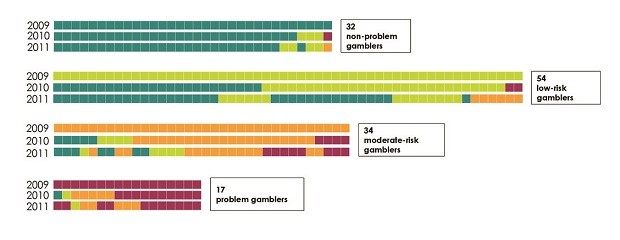

Results from a recent longitudinal study conducted in Quebec reveal:

1. General decreases in problem gambling over specified periods of time;

2. A heterogeneity in the ways these changes occur dependent on the severity of problems :

- Gamblers who are at low-risk for problems are the most likely to remain stable over time: 97% of gamblers who did not report any problems and 85% of gamblers who are at low-risk for problems.

- Gamblers who are at moderate-risk for problems are less stable over time: 1/3 reported more severe problems, 1/3 remained at a moderate level of problems, 1/3 reported low-level of problems or no problems at all after two years.

- Most of the problem gamblers’ scores remained high over the three waves: 47.1% transitioned to the moderate-risk zone and then either relapsed or stabilized as moderate-risk gamblers over the two-year follow-up.

The Quebec findings replicate previous results [2-9].

Figure 1: Individual Transitions of gamblers over 24 months

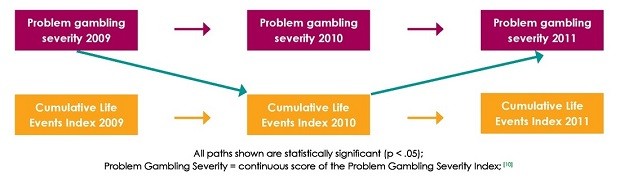

The influence of life events on gambling trajectories

There is a recursive effect between problem gambling severity and the cumulative number of life events [10]: (figure 2)

1. Gambling in 2009 impacted on the number of negative life events reported by gamblers one year later in 2010;

2. The total number of life events that gamblers experienced in 2010, as an indication of the amount of stress in their life, affected the level of severity of problem gambling one year later, in 2011.

Figure 2: Association between problem gambling severity and cumulative life events

The Quebec findings replicate previous findings that:

- Routine daily stressors have been linked to spontaneous urges to gamble among adult problem gamblers [11];

- Changes in emotional states such as distress, depression or anxiety and the worsening of one’s financial situation have all been associated with gambling initiation and changes in severity of gambling problems [12-15].

Relationship between specific life events and problem gambling severity among gamblers in Québec

The occurrence of specific life events and change in specific life domains were associated with higher levels of severity of problem gambling a year later in 2011 **. (Figure 3).

These results were also found in previous studies: Significant life events and changes in lifestyle - financial, professional, personal and social - have been associated with the emergence and maintenance of gambling problems and with relapse [4, 16].

Figure 3: Significant Life domains identified in 2010 that affected the severity of

problem gambling one year later (2011)

* Problem gambling refers to both categories combined of moderate-risk and problem gamblers of the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) [17].

** PGSI scores in 2011 were used to test the association with 41 different individual events that occurred in 2010. For more details, see Luce et al., 2016 [10].

Methodology

The sample of this study was recruited from the general gambling population survey conducted in Quebec through telephone interviews with 11,888 participants in 2009. Based on their PGSI score [17], all problem gamblers (n = 60), moderate-risk gamblers (n = 138), low-risk gamblers (n = 262), and a group of 54 randomly selected non-problem gamblers were asked to participate in a follow-up study about gambling. Overall, 137 gamblers completed the 3 follow-up studies. The first wave was conducted within 4 weeks following the survey whereas Wave 2 and 3 were conducted 12 months and 24 months later. At all three waves, gambling status was measures using the PGSI index, and the Social Readjustment Rating Scale was used to evaluate the presence of 41 major life events [18]. A scale to measures an individual’s level of stress was created by summing the number of reported events [19](For more details on the methodology of the study, see Luce et al., 2016 [2, 10]).

References

- Kairouz, S., Paradis, C., Nadeau, L., Hamel, D., & Robillard, C. (2015). Patterns and trends in gambling participation in the Quebec population between 2009 and 2012. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106, 115–120.

- Luce, C., Nadeau, L., & Kairouz, S. (2016). Pathways and transitions of gamblers over two years. International Gambling Studies, 1–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1209780

- Abbott, M. W., Stone, C. A., Billi, R., & Yeung, K. (2016). Gambling and problem gambling in Victoria, Australia: Changes over 5 years. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32, 47–78.

- Billi, R., Stone, C. A., Marden, P., & Yeung, K. (2014). The Victorian gambling study: A longitudinal study of gambling and health in Victoria, 2008–2012. North Melbourne, AU: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation

- Challet-Bouju, G., Hardouin, J.-B., Vénisse, J.-L., Romo, L., Valleur, M., Magalon, D., Grall-Bronnec, M. (2014). Study protocol: The JEU cohort study—Transversal multiaxial evaluation and 5-year follow-up of a cohort of French gamblers. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 226.

- el-Guebaly, N., Casey, D. M., Currie, S. R., Hodgins, D. C., Schopflocher, D. P., Smith, G. J., & Williams, R. J. (2015). The Leisure, Lifestyle, & Lifecycle Project (LLLP): A longitudinal study of gambling in Alberta. Final report for the Alberta Gambling Research Institute (AGRI).

- Reith, G., & Dobbie, F. (2013). Gambling careers: A longitudinal, qualitative study of gambling behaviour. Addiction Research & Theory, 21, 376–390. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(5), 373-390.

- Slutske, W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological, gambling: Results of two U.S. national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 297–302.

- Williams, R. J., Hann, R. G., Schopflocher, D., West, B., McLaughlin, P., White, N., … Flexhaug, T. (2015). Quinte longitudinal study of gambling and problem gambling. Report of the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

- Luce, C., Kairouz, S., Nadeau, L., & Monson, E. (2016) Life events and problem gambling severity : A prospective study of adult gamblers, Psychology of Addictive Behaviours.

- Elman, I., Tschibelu, E., & Borsook, D. (2010). Psychosocial stress and its, relationship to gambling urges in individuals with pathological gambling. The American Journal on Addictions, 19, 332–339.

- Abbott, M. W. (2012, April). Pacific islands longitudinal families study. Paper presented at the Annual Alberta Gambling Research Institute Conference, Banff, Alberta, Canada.

- Abbott, M. W., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2014). New Zealand 2012 national gambling study: Gambling harm and problem gambling (Research Report No. 2). Auckland, New Zealand: Gambling and Addictions Research Centre.

- Shaffer, H. J., & Hall, M. N. (2002). The natural history of gambling and drinking problems among casino employees. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 405– 424.

- Wiebe, J., Cox, B., & Falkowski-Ham, A. (2003). Psychological and social factors associated with problem gambling in Ontario: A one year follow-up study. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

- Bergevin, T., Gupta, R., Derevensky, J., & Kaufman, F. (2006). Adolescent gambling: Understanding the role of stress and coping. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22, 195–208.

- Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

- Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

- Scully, J. A., Tosi, H., & Banning, K. (2000). Life event checklists: Revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 864–876.

Consult the pdf version of this factsheet here.

LE NOUVEAU VISAGE DU JEU EN LIGNE

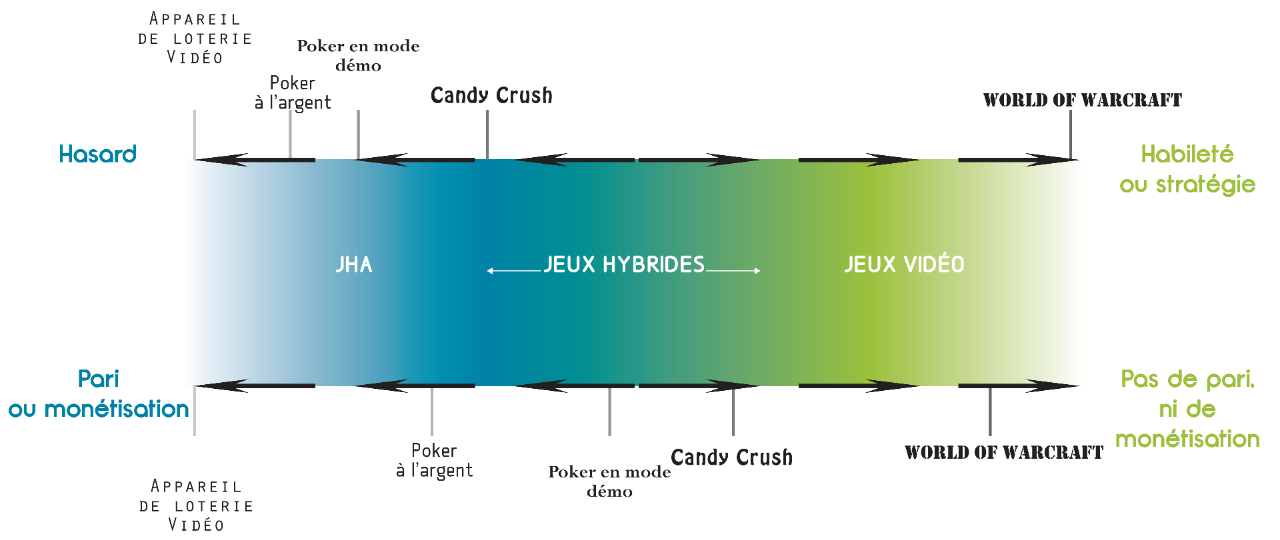

À une époque pas si lointaine que ça, les jeux de hasard et d’argent (JHA) étaient presque l’exclusivité des casinos, de quelques bars ou de sous-sols où se jouaient quelques parties de poker entre amis. Depuis l’avènement de l’univers « en ligne » et des nouvelles technologies, les JHA sont de plus en plus accessibles et ce dans une multitude de lieux et de contextes : à la maison sur son ordinateur, sur son cellulaire, par exemple en attendant l’autobus ou bien sur sa tablette électronique quand on fait de l’insomnie. L’univers en ligne a ouvert la porte à de nouvelles formes de jeux hybrides qui nous invitent à revoir notre façon de définir les JHA et nous met face à de nouveaux défis soulevés par cette nouvelle génération de jeu pour la recherche et l’intervention. Ce billet vise à ouvrir une réflexion sur les nouvelles formes de jeux en ligne, leur consommation, leur potentiel addictif et les enjeux qu’ils soulèvent pour l’intervention.

La nouvelle génération de JHA: les JHA hybrides

Les JHA hybrides sont des jeux digitalisés qui ont émergés par l’effet de deux types de transformation des produits du jeu (voir Figure). Le jeu hybride résulte, dans certains cas, de l’application aux JHA de contenus propres aux jeux vidéo, tel un facteur d’habileté du joueur ou une plus grande interactivité dans le jeu (processus de ludification). À l’inverse, le jeu hybride peut intégrer dans les jeux vidéo des caractéristiques propres aux JHA, telle l’instauration dans le jeu de systèmes de microtransactions qui permettent l’achat d’items pour gagner des privilèges au jeu, l’insertion de possibilités de mises d’argent, ou d’éléments de chance (processus de gamblification) (Gainsbury, King, Abarbanel, Delfabbro et Hing, 2015). Les entreprises de jeu génèrent leurs revenus à travers ces microtransactions, dont le processus global est désigné par le terme « monétisation » (De Rosa et Burgess, 2014). Ces hybrides ont envahi les réseaux sociaux comme Facebook et font désormais partie intégrante de l’environnement en ligne. Une récente étude a déterminé que 54 des 100 jeux les plus populaires sur Facebook, qui ne sont pas classifiés comme des JHA, présentent pourtant du contenu de JHA (Jacques et al., 2016).

Les JHA hybrides sont omniprésents. Ces jeux en ligne et les crédits nécessaires pour y jouer sont accessibles instantanément. Il ne suffit que d’un clic et vous voilà plongé dans un jeu conçu pour être le plus stimulant possible. Via le téléphone intelligent ou encore Facebook, on ne manquera pas l’opportunité de vous rappeler de jouer et de dépenser quelques crédits réels, mais intangibles (Reith, 2015).

Les JHA hybrides sont personnalisés. L’industrie du jeu en ligne cherche continuellement à personnaliser les plateformes et les expériences de jeu selon votre profil en enregistrant des données sur vos comportements et votre localisation (Reith, 2015). À travers les informations qu’ils collectent en temps réel sur ses joueurs, les opérateurs peuvent même altérer l’expérience du joueur. Par exemple, certains jeux font parvenir au joueur des messages personnalisés basés sur l’historique de jeu et les préférences (Reith, 2015).

Les JHA hybrides misent sur le temps. La grande accessibilité des hybrides et leur caractère hautement stimulant garderaient le joueur « scotché » à son écran et l’empêcherait de réaliser des activités quotidiennes importantes. Certains auteurs considèrent que le temps passé en excès au jeu est un temps emprunté à d’autres activités essentielles : ce temps monopolisé au jeu viendrait transformer littéralement notre quotidien et nos priorités (Vihelmson, Thulin et Elldér, 2016) et nous laisse avec cette dette de temps empruntée à d’autres sphères importantes de notre vie, le travail, les études, ou plus fondamentalement l’alimentation, le sommeil ou la socialisation (Vihelmson et al, 2016). Ce déséquilibre dans l’allocation du temps pourrait devenir une source de problèmes et de méfaits potentiels pour le joueur et son entourage.

Intervention

En terme d’intervention, les jeux hybrides posent de nombreux défis pour les intervenants. Peut-on réellement demander à un joueur problématique de s’exclure des réseaux sociaux où les jeux hybrides comme Candy Crush Saga sont présents massivement? Peut-on lui demander tout simplement de cesser d’utiliser son ordinateur ou son téléphone intelligent pour éliminer la tentation? Considérant la place occupée par la technologie dans notre vie quotidienne cela semble compliqué, voire irréaliste. Les intervenants évoluent ici probablement dans une situation requérant une gestion du temps. C’est la répartition du temps entre activités en ligne et autres activités qui définit en grande partie le type d’utilisateur (Vihelmson et al, 2016). Un individu qui accorde trop de temps aux jeux en ligne doit donc apprendre à gérer ce temps et à le redistribuer dans des activités quotidiennes. Tout comme l’argent dépensé dans les jeux, le temps utilisé pour jouer est emprunté sur des activités essentielles et il faut le redonner à ces activités afin de réduire les effets collatéraux d’un excès d’utilisation des produits présents sur internet et d’une dépendance au jeu en ligne.

Le contenu de ce feuillet a été initialement publié sur le site de l’Association des intervenants en dépendance du Québec (AIDQ) le 30 septembre 2016 : Le nouveau visage des jeux en ligne

Auteurs:

Sylvia Kairouz

Philippe Laperle

Frédéric Dussault

Références

- De Rosa, M. et Burgess, M. (2014). Monétisation des médias numériques. Tendances, observations et stratégies efficaces. Ontario : Alliance canadienne interactive.

- Gainsbury, S., King, D., Abarbanel, B., Delfabbro, P. et Hing, N. (2015). Convergence of gambling and gaming in digital media. Victoria, Australie : Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

- Jacques, C., Fortin-Guichard, D., Bergeron, P-Y., Boudreault, C., Lévesque, D. et Giroux, I. (2016). Gambling content in Facebook games : A common phenomenon? Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 48-53.

- Reith, G. (2015). Gambling 2 : A political economy of mobile and social gambling. Communication présentée au Symposium Interactif d’été : Recherche 2.0, Montréal, Québec. Repéré à https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/artsci/research/lifestyle-addiction/docs/events/summer-school-2015/Reith_SIS_June2015.pdf

- Vihelmson, B., Thulin, E. et Elldér, E. (2016). Where does time spent on the Internet come from? Tracing the influence of information and communications technology use on daily activities. Information, Communication & Society, 1-14.

Consult the pdf version of the factsheet No 4 here.

PATTERNS AND TRENDS IN GAMBLING

PARTICIPATION IN QUEBEC

BETWEEN 2009 AND 2012

This factsheet was prepared by the Research Chair on Gambling Studies in collaboration with the Centre de réadaptation en dépendance de Montreal and the CIUSSS du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal.

Context

In Canada, a significant portion of public funds is allocated to the prevention of harm associated with certain gambling practices as well as the treatment of problem gambling. The allocation of resources must be based on valid prevalence data that reports gambling patterns and trends in the general population.1,2

This fact sheet presents an overview of the situation in Quebec by presenting trends in gambling participation as well changes in the proportion of at-risk gamblers in the adult population between 2009 and 2012.

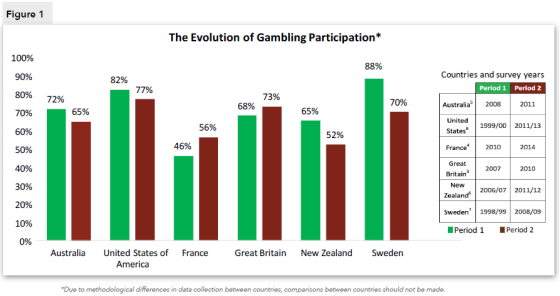

The most recent prevalence studies have revealed a global trend of decreased gambling participation in many countries, despite a small number of countries where the prevalence has increased, notably France4 and the United Kingdom3 (Figure 1). Problem gambling prevalence rates have remained stable.3-8

Quebec

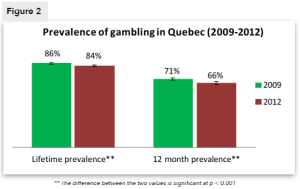

The proportion of Quebeckers who have never gambled in their lifetime increased between 2009 and 2012, which might suggest a decrease in the popularity of gambling among the province’s adult population.1,2 Furthermore, the proportion of individuals who have bet or wagered money on at least one gambling activity over the course of the last year decreased significantly over the same time period (Figure 2).1,2

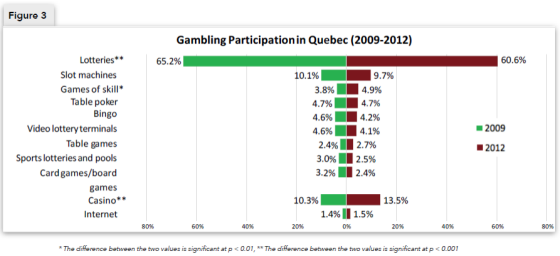

Participation rates vary according to gambling activity. For example, lottery participation decreased significantly between 2009 and 2012 while games of skill became more popular. The rate of participation in online gambling in Quebec remained stable while gambling in casinos increased (Figure 3).1,2

Gambling participation is higher among men, individuals aged 45 to 65, those active in the labor market and among individuals holding secondary or collegial diplomas. Moreover, gambling participation is significantly lower among single people as well as among individuals who reported a family revenue of less than $20,000 (not shown).1,2

The differences in participation rates between subgroups of the population persist between 2009 and 2012. In short, this means that the decrease in participation for the general population cannot be attributed to any specific subgroup.1,2

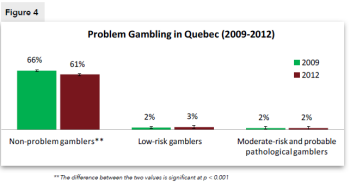

Between 2009 and 2012, the prevalence of problem g ambling remained unchanged, while the prevalence of non-problem gam-bling decreased significantly

(Figure 4 ).2

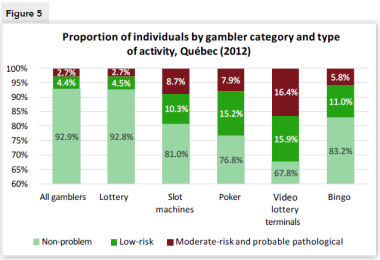

The proportion of problem gamblers varies according to type of gambling activity (Figure 5). When compared to the distribution of problem gambling for all activities combined, the proportion of problem gam-blers is significantly higher among those playing slot machines, poker, video lottery terminals and bingo (p < 0.05).2

Methodology

Results are drawn from the ENHJEU-Québec Survey, Portait of gambling in Quebec: Prevalence, incidence, and trajectories over four years (2009-2012),2 conducted with non-institutionalized individuals aged 18 years or older living in private residences throughout the province of Quebec. The survey data was collected by means of telephone interviews with 11,888 participants in 2009 and 12,008 in 2012. Gambling participation was measured as having wagered money on at least one of the following eleven activities: lottery, bingo, horse races, slot machines, video lottery terminals, poker, table games, keno, sports betting, card games, or games of skill.

To reflect the gravity of their gambling problems, gamblers were classified according to the four categories of the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI).9

| CATEGORY OF GAMBLER* | SCORE |

| Non-problem gamblers | 0 |

| Low-risk gamblers | 1 to 2 |

| Moderate-risk gamblers | 3 to 7 |

| Probable pathological gamblers | 8 + |

* Because of the small number of probable pathological gamblers, the moderate risk and probably pathological categories were merged in order to constitute a single category of problem gamblers.

Conclusion

This study reveals a significant decrease in the proportion of gamblers in Quebec. This decrease has occurred despite an increase in gambling opportunities in the province, in particular, the opening of a new casino in Mont Tremblant (2009) and the launch of the province’s new online gambling website Espacejeux (2010). With the evolution of online gaming/gambling platforms, for example new online sports betting opportunities, growth in gambling supply is projected to continue.1,2 Sustained vigilance is needed.

While the overall proportion of gamblers is decreasing in Quebec, the prevalence of problem gamblers has remained stable. Therefore, it is important that public resources allocated to problem gambling initiatives are maintained, as well as those for secondary prevention measures targeting vulnerable populations.1,2

Interprovincial comparisons are called for in order to shed light on the effects that the ongoing legalization of online gambling opportunities may have on gambling practices and associated problems.

References

- Kairouz, S., Paradis, C., Nadeau, L., Hamel, D., & Robillard, C. (2015). Patterns and trends in gambling participation in the Quebec population between 2009 and 2012. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 115-120.

- Kairouz, S., & Nadeau, L. (2014, février 14). Enquête ENHJEU-Quebec: Portrait du jeu au Québec: Prévalence, incidence et trajectoires sur quatre ans. https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/artsci/research/lifestyle-addiction/docs/projects/enhjeu-q/ENHJEU-QC-2012_rapport-final-FRQ-SC.pdf

- Wardle, H., Moody, A., Spence, S., Ordord, J., Volberg, R., Jotangia, D., et al. (2010). British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. London, UK: National Centre for Social Research, 2010.

- Costes, J.-M., Eroukmanoff, V., Richard, J.-B., & Tovar, M.-L. Les Jeux d'Argent et de Hasard en France en 2014. Les notes de l'Observatoire des Jeux 2015, 6, 1-9. http://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/note_6.pdf

- Christensen, D. R., Dowling, N.A., Jackson, A. C., & Thomas, S.A. (2014). Gambling participation and problem gambling severity in a stratified random survey: Findings from the second Social and Economic Impact Study of Gambling in Tasmania. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29, 1–19

- Rossen, F. (2015). Gambling and problem gambling: Results of the 2011/12 New Zealand Health Survey. Auckland, NZ: Centre for Addiction Research.

- Abbott, M.W., Romild, U., & Volberg, R. A. (2014). Gambling and problem gambling in Sweden: Changes between 1998 and 2009. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(4), 985–999.

- Welte, J. W., Barnes, G. M., Tidwell, M. C. O., Hoffman, J. H., & Wieczorek, W.F. (2015). Gamblign and problem gambling inthe United States: Changes between 1999 and 2013. Journal fo Gamblig STudies, 31(3), 695-715

- Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Consult the pdf version of this fact sheet.

HISTORY OF GAMBLING IN QUEBEC (1882-1970)

Approaches to the regulation of gambling in Quebec have oscillated from moral condemnation to acceptance in the name of charity or in the interest of profit. Authorities have, at various times, legalized, prohibited, and turned a blind eye to gambling.

Context

Gambling was prohibited by the Federal government unless overseen by a charitable organization. As a general rule, Catholics were more tolerant of gambling than Protestants.

Significant events

- In 1882, Father Antoine Labelle, commonly known as Curé Labelle (see portrait to right; Le Curé Labelle vers 1880, n.d.), established a national lottery to fund the Société de colonisation du diocèse de Montréal which strove to establish Montreal as a French colony. His project was accepted by the Provincial Assembly, but rejected by the Legislative Council. Regardless, the first draw took place in 1884.

- In 1888, the Liberal government under Honoré Mercier recruited Curé Labelle, and in 1890, a new lottery was established, this time to benefit the SaintJean-Baptiste Association, a Quebec nationalist group.

- In 1892, the House of Commons, influenced by Christian moralist groups, enacted the Canadian Criminal Code in which gambling was formally prohibited except in the cases of horse racing, lotteries for art pieces, and wheel of fortune games at agricultural fairs.

Context

Christian moralists made use of the Criminal Code to prosecute those who had sinned by gambling, especially newcomers. However, their influence diminished over time.

Significant events

- In 1905, Quebecker notary Alphonse Huard published an article in which he proposed extending the scope of the temperance movement to include gambling.

- World War I led to a proliferation of patriotic themed raffles and lotteries. It became common for veterans to gamble when they returned from active duty without concern for Christian judgement.

- The Great Depression of 1929 made it clear to Quebecers that the capitalist economy is not based on work and savings as taught by Christian doctrine, but rather on speculation.

Context

During the 1930s, non-Protestant immigrants (Irish, Italian, Jewish, Chinese) established illegal gambling houses that would eventually become Montreal’s Red Light District, centered around the intersection of Sainte-Catherine and Saint-Laurent streets. Profits allowed them to establish solid infrastructures, adapt games to technological advances, and to fund other illicit activities. During the 1940s, magazines such as Liberty and Maclean's estimated annual gaming revenue to be $100 million.

Significant events

- Several countries such as France, Spain, and Australia legalized lotteries in the 1930s. Quebec politicians, including then mayor of Montreal, Camillien Houde, were unsuccessful in their campaigns to follow suit.

- Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes became popular in Quebec.

- In 1946, Louis Bercowitz assassinated gambling magnate Harry Davis and turned himself in to the police. Five days later, Arthur Taché, head of the Montreal Police Service, resigned in response to allegations made against him. Pacifique Plante was then appointed as head of the police “morality squad” (see image above; Montréal Sous le Règne de la Pègre/Pacifique Plante, n.d.). These events heralded the beginning of the end of the Prohibition era.

Context

Gambling was no longer perceived as a sin, but as a source of revenue for organized crime, and was therefore viewed as responsible for corruption.

Significant events

- Pacifique Plante declared war on illegal gambling, going so far as to threaten priests who organized bingo games to benefit their parishes. Despite the efficiency of his actions, his employment was terminated in 1948 for political reasons. He responded by writing a series of articles denouncing the police and the municipal government for protecting organized crime. In 1950, the Public Morality Committee (later renamed the Civic Action League), led by Pacifique Plante and Jean Drapeau, launched the Caron Inquiry, known as the investigation of the century, to examine the activity of Montreal police officers, and blaming the heads of the Montreal Police Department for being tolerant of organized crime. Jean Drapeau became mayor of Montreal in 1954.

- In 1956, the Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on Capital Punishment, Corporal Punishment and Lotteries tabled a report recommending stronger federal laws against gambling.

- In 1957, the psychoanalyst Edmund Bergler published a book on the subject of pathological gambling; it was the first contemporary academic publication on the issue.

Context

According to 1955 Gallup polls, 69% of Canadians supported the legalization of lottery, with 23% opposed. The same poll in 1969 recorded increased support to 79% versus 14% opposed.

Significant events

- In late 1967, Pierre-Elliot Trudeau, then Minister of Justice under Lester B. Pearson, introduced the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1968-1969. The omnibus bill modified several of the Criminal Code’s moral transgressions, either by decriminalization (e.g., homosexual practices between consenting adults), or conditional legalization (e.g., medically necessary abortion and lotteries). After becoming leader of the Liberal party, Trudeau made this amendment project the cornerstone of his successful 1968 federal election campaign. The bill was passed on May 14th, 1969 and came into effect on January 1st, 1970. The amendment authorized provincial governments to operate lotteries.

- In 1968, Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau established a form of public lottery known as the “voluntary tax” as a fiscal tool to decrease the city’s fiscal deficit. The Supreme Court of Canada declared it illegal on December 22nd, 1969.

- On December 23rd , 1969, Quebec adopted the Lotteries and Races Act. On March 14th, 1970, Quebecers participated in the first draw organized by the Société d’exploitation des loteries et des courses du Quebec (Loto-Québec). Two immigrants shared the $125,000 jackpot.

References

Bergler, E. (1957). Psychology of Gambling. New York, NY: Hill & Wang.

Brodeur, M. (2011). Vice et corruption à Montréal: 1892-1970. Quebec, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Campbell, C. S., & Smith, G. J. (2003). Gambling in Canada: From vice to disease to responsibility: A negotiated history. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 20(1), 121-149.

Chaffey, D. C. (1993). The right to privacy in Canada. Political Science Quarterly, 108(1), 117-132.

Cellard, A., & Pelletier, G. (1998). Le Code criminel canadien 1892-1927: Étude des acteurs sociaux. Canadian Historical Review, 79(2), 261-303.

Gadbois, J. (2012). Ethnologie du Lotto 6/49: Esquisses pour une définition de la confiance (Doctoral dissertation). Université de Laval, Québec and EHESS, Paris.

Guay, J.-H. (n.d). Présentation du premier tirage de Loto-Québec. Retrieved from http://bilan.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/pages/ evenements/20059.html

Labrosse, M. (1985). Les loteries: De Jacques Cartier à nos jours: La petite histoire des loteries au Québec. Montreal, QC: Stanké.

Morton, S. (2003). At odds: Gambling and Canadians, 1919-1969. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Osborne, J. A. (1989). The legal status of lottery schemes in Canada: Changing the rules of the game (Master’s thesis). University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Roy, J.-P. et al. (1983). Dossier Loto-Québec. Montreal, QC: Loto-Québec.

Image sources

(n.d.). Le curé Labelle vers 1880 [digital image]. Récupéré de http://grandquebec.com/gens-du-pays/biographie-labelle/

(n.d). Montréal Sous le Règne de la Pègre/Pacifique Plante [digital image]. Récupéré de http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/archives/democratie/democratie_en/expo/crises-reformes/ pegre/piece1/index.shtm

Consult the fact sheet in pdf format here.

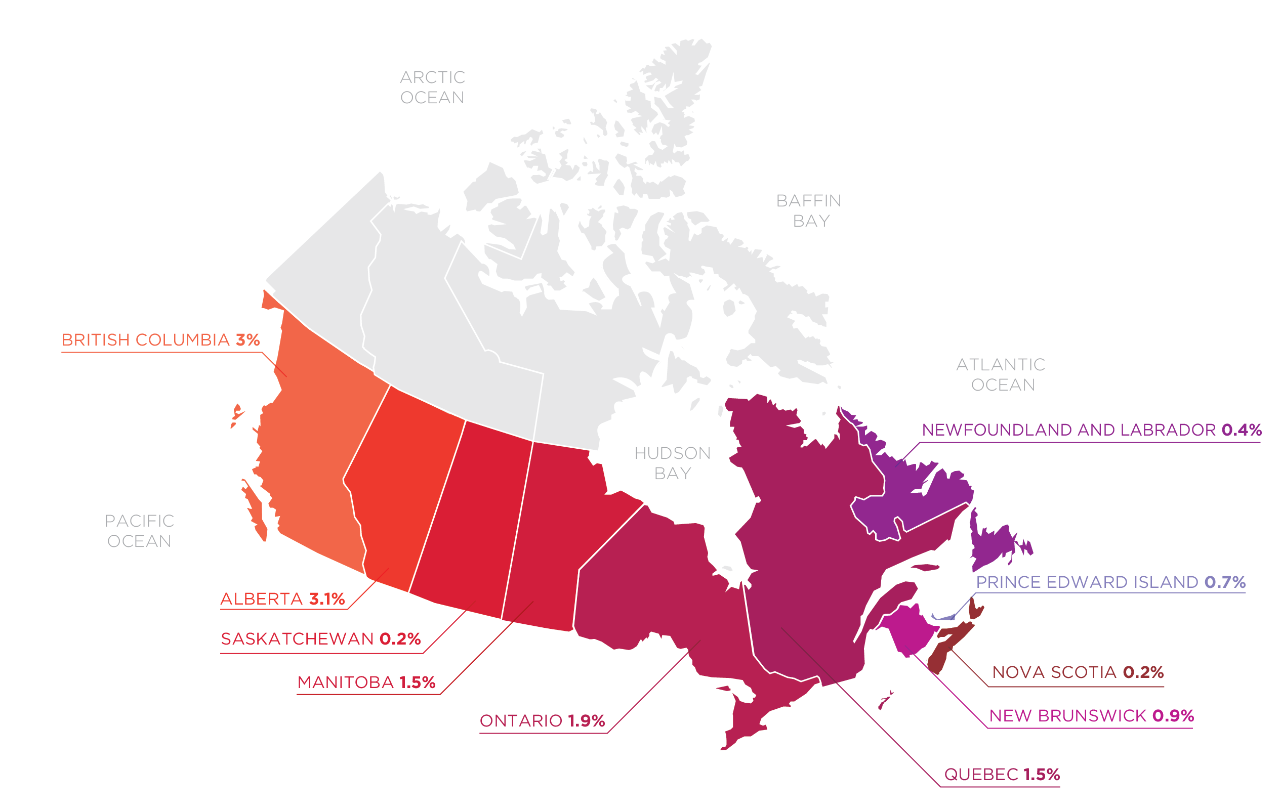

PREVALENCE OF ONLINE GAMBLING

Across the world

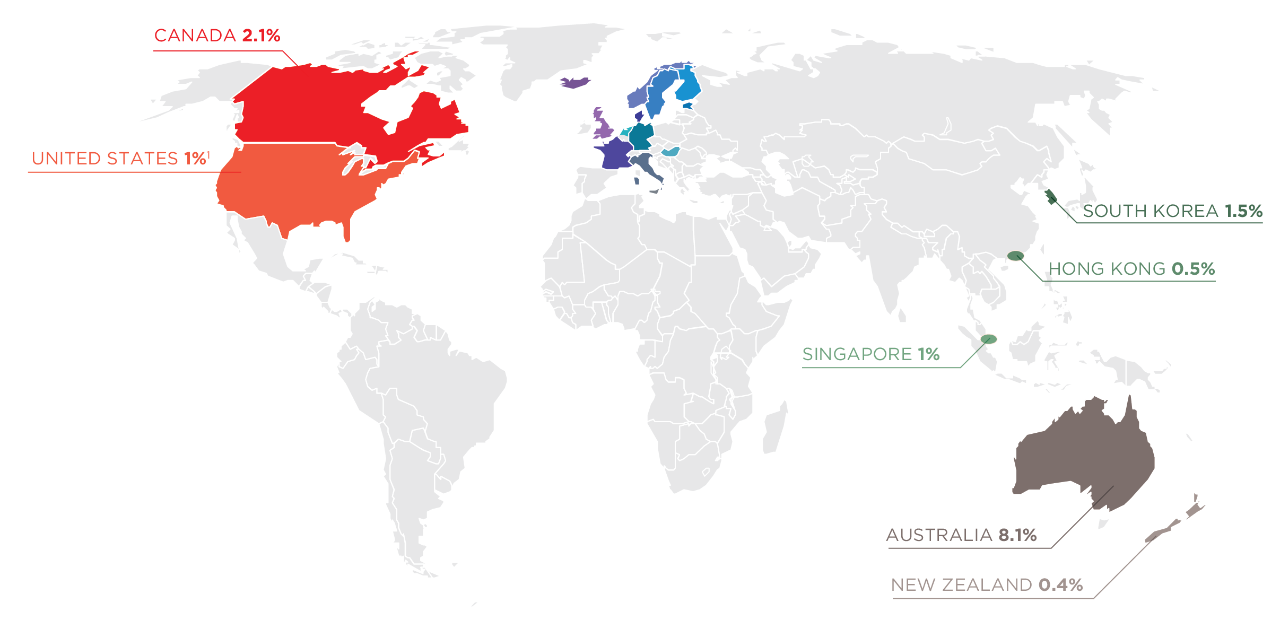

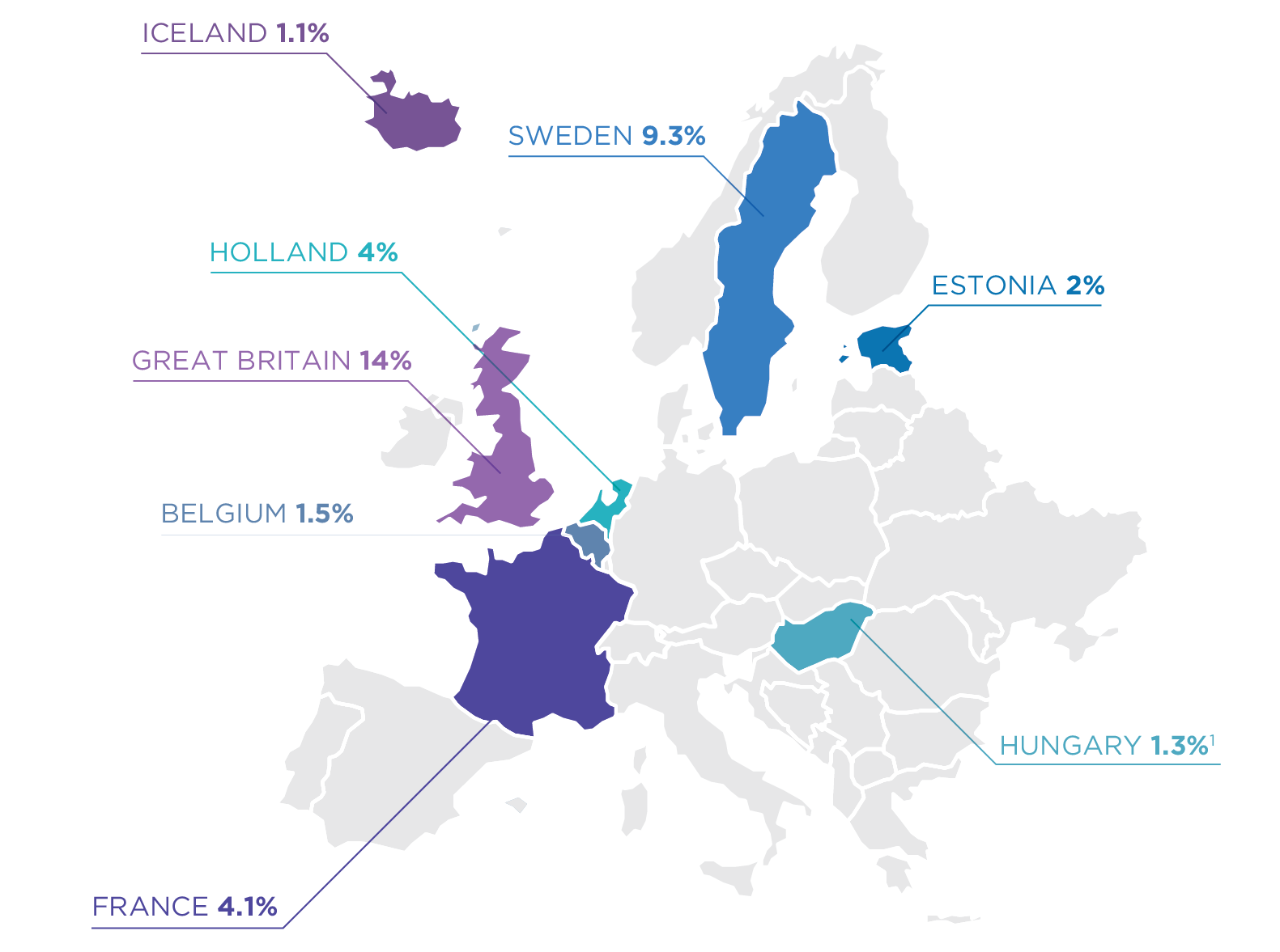

The prevalence of online gambling in the adult population varies across the world between 0.4% in New Zealand and 14% in Great Britain.

In Canada

The prevalence of online gambling is estimated at 2.1% in the Canadian population and varies between provinces; from 0.2% in Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan to 3.1% in Alberta. It is estimated at 1.5% in Quebec.

Methodology

A review of national surveys was conducted on the prevalence of online gambling between 2001 and 2013, in different countries, in Canada, as well as in each Canadian province. Percentages correspond to the prevalence in the past 12 months, unless stated otherwise. The methodological details of each survey are available in the original documents cited in the references.

References

Africa

South Africa

Collins, P. & Barr, G. (2009). Gambling and Problem Gambling in South Africa: A Comparative Report. A report prepared for the South African Responsible Gambling Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.responsiblegambling.co.za/media/user/documents/NRGP%20Comparative%20Report%20-%20June%202009.pdf.

Asia

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2012). The Study of Hong Kong People's Participation in Gambling Activities. Department of Applied Social Sciences. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Commissioned by the Secretary for Home Affairs, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. March 2012. Retrieved from http://www.hab.gov.hk/file_manager/en/documents/policy_responsibilities/others/gambling_report_2011.pdf.

Singapore

National Council on Problem Gambling (2012). Report of Survey on Participation in Gambling Activities among Singapore Residents, 2011. Singapore: Author. February 23, 2012. Retrieved from http://app.msf.gov.sg/Portals/0/Summary/research/EDGD/Gambling%20participation%20survey%202011.pdf.

South Korea

Williams, R.J., Lee, C-K., & Back, K-J. (2013). The Prevalence and Nature of Gambling and Problem Gambling in South Korea. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 821–834.

Europe

Belgium

Druine (2009). Belgium. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

Denmark

Bonke, J., & Borregaard, K. (2006). The Prevalence and Heterogeneity of At-Risk and Pathological Gamblers - The Danish Case (Working Paper 15: 2006). Danish National Institute of Social Research. Retrieved from http://www.sfi.dk/publications-4844.aspx?Action=1&NewsId=168&PID=10056.

Estonia

Laansoo & Niit (2009). Estonia. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

France

Costes, J.-M., Eroukmanoff, V., Richard, J.-B., & Tovar, M.-L. (à paraître). Les pratiques de jeux d’argent et de hasard en France en 2014. Observatoire des jeux (ODJ), (6), 9.

Great Britain

Wardle, H., Moody, A., Spence, S., Orford, J., Volberg, R., Jotangia, D., Griffiths, M., Hussey, D., & Dobbie, F. (2011). British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. Prepared for The Gambling Commission. London: National Centre for Social Research Retrieved from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/British%20Gambling%20Prevalence%20Survey%202010.pdf.

Holland

Goudriaan et al (2009). The Netherlands. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

Hungary

Kun B., Balázs H., Arnold, P., Paksi, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2011). Gambling in western and eastern Europe: The example of Hungary. Journal of Gambling Studies. doi:10.1007/s10899-011- 9242-4.

Iceland

Ólason, D.T. (2009). Gambling and Problem Gambling Studies among Nordic Adults: Are they Comparable? Conference

presentation @ 7th Nordic Conference, Helsinki, Finland, May, 2009.

Sweden

Abbott, M.X., Romild, U., & Volberg, R.A. (2013). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Sweden: Changes Between 1998 and 2009. Journal of Gambling Studies, DOI 10.1007/s10899-013- 9396-3.

North America

Canada

Wood, R.T. & Williams, R.J. (2009). Internet Gambling: Prevalence, Patterns, Problems, and Policy Options. Final Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, Guelph, Ontario. January 5, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/0909_ originalreport.pdf.

United States

Kessler, R.C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N.A., Winters, K.C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine,38(9), 1351-1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900

Pacific

Australia

Gainsbury et al. (2013). How the Internet is Changing Gamblng: Findings from an Australian Prevalence Survey. Journal of Gambling Studies. DOI 10.1007/s10899-013-9404-7

New Zealand

Mason, K. (2009). A Focus on Problem Gambling: Results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/ publication/focus-problem-gambling-results-2006-07-new- zealand-healthsurvey.

Province

Alberta

Williams, R.J., Belanger, Y.D., & Arthur, J.N. (2011). Gambling in Alberta: History, Current Status, and Socioeconomic Impacts. Final Report to the Alberta Gaming Research Institute. Edmonton, Alberta. April 2, 2011. Appendix A: 2008 and 2009 Alberta Population Surveys.

British Columbia

Ipsos-Reid & Gemini Research. (2008). British Columbia Problem Gambling Prevalence Study. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. Retrieved from https://www.gaming.gov.bc.ca/reports/docs/rpt-rg-prevalence-study-2008.pdf.

Manitoba

Lemaire, J., MacKay, T., & Patton, D. (2008). Manitoba gambling and problem gambling 2006. Winnipeg, MB: Addictions Foundation of Manitoba. Retrieved from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba web site: http://www.afm.mb.ca

New Brunswick

MarketQuest Research. (2010). 2009 New Brunswick Gambling Prevalence Study. Prepared for Department of Health and New Brunswick Lotteries and Gaming Corporation, Government of New Brunswick. Fredericton, NB.

Newfoundland and Labrador

MarketQuest Research (2009). 2009 Newfoundland and Labrador Gambling Prevalence Study. Prepared for Department of Health and Community Services, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John's, NL: Department of Health and Community Services. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publications/2009_gambling_study.pdf.

Northwest Territories

NWT Addictions Report. Prevalence of alcohol, illicit drug, tobacco use and gambling in the Northwest Territories. (2010). Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. Retrieved from http://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/default/files/nwt_addictions_report.pdf.

Nova Scotia

Focal Research Consultants (2008). 2007 Adult Gambling Prevalence Study. Halifax, NS: Nova Scotia Health Promotion and Protection. Retrieved from http://www.nsgamingfoundation.org/uploads/Adult_Gambling_Report.pdf.

Ontario

Williams, R.J. & Volberg, R.A. (2013). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Ontario. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. June 17, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.uleth.ca/dspace/handle/10133/3378.

Prince Edward Island

Doiron, J. (2006). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Prince Edward Island. Submitted to Prince Edward Island Department of Health. Retrieved from http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/doh_GambReport.pdf.

Quebec

Kairouz, S., & Nadeau,L. (2014). Portrait du jeu au Québec: Prévalence, incidence et trajectoires sur quatre ans. Montreal, QC: Université Concordia. Retrieved from http://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/concordia/research/lifestyle-addiction/docs/ENHJEU-QC 2012 - RAPPORT FINAL FRQ-SC.pdf.

Saskatchewan

Wynne, H. (2002). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Saskatchewan: Final Report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.sk.ca/adx/aspx/adxGetMedia.aspx?DocID=317,94,88,Documents&MediaID=166&Filename=gambling-final-report.pdf.

Download the fact sheet in PDF format.

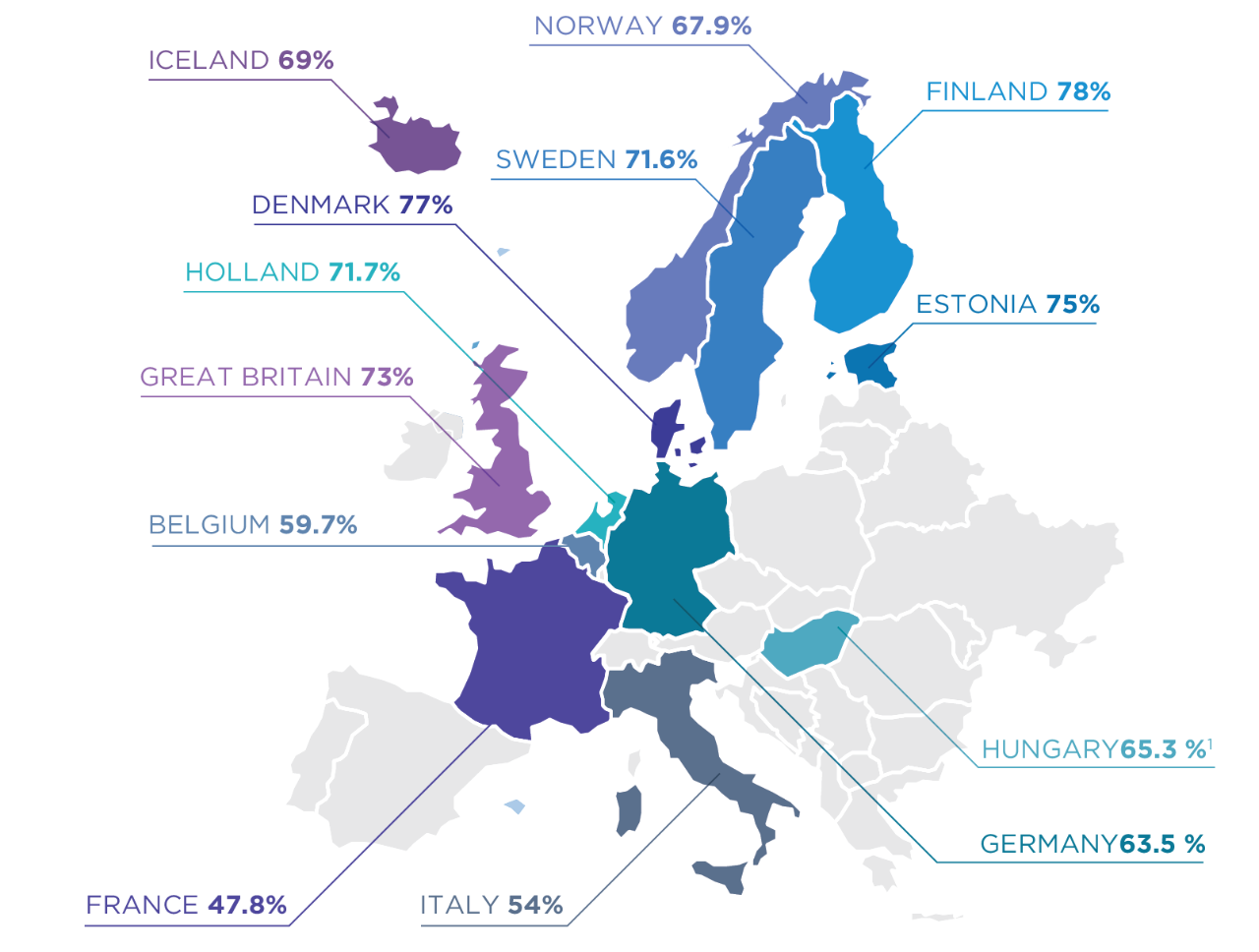

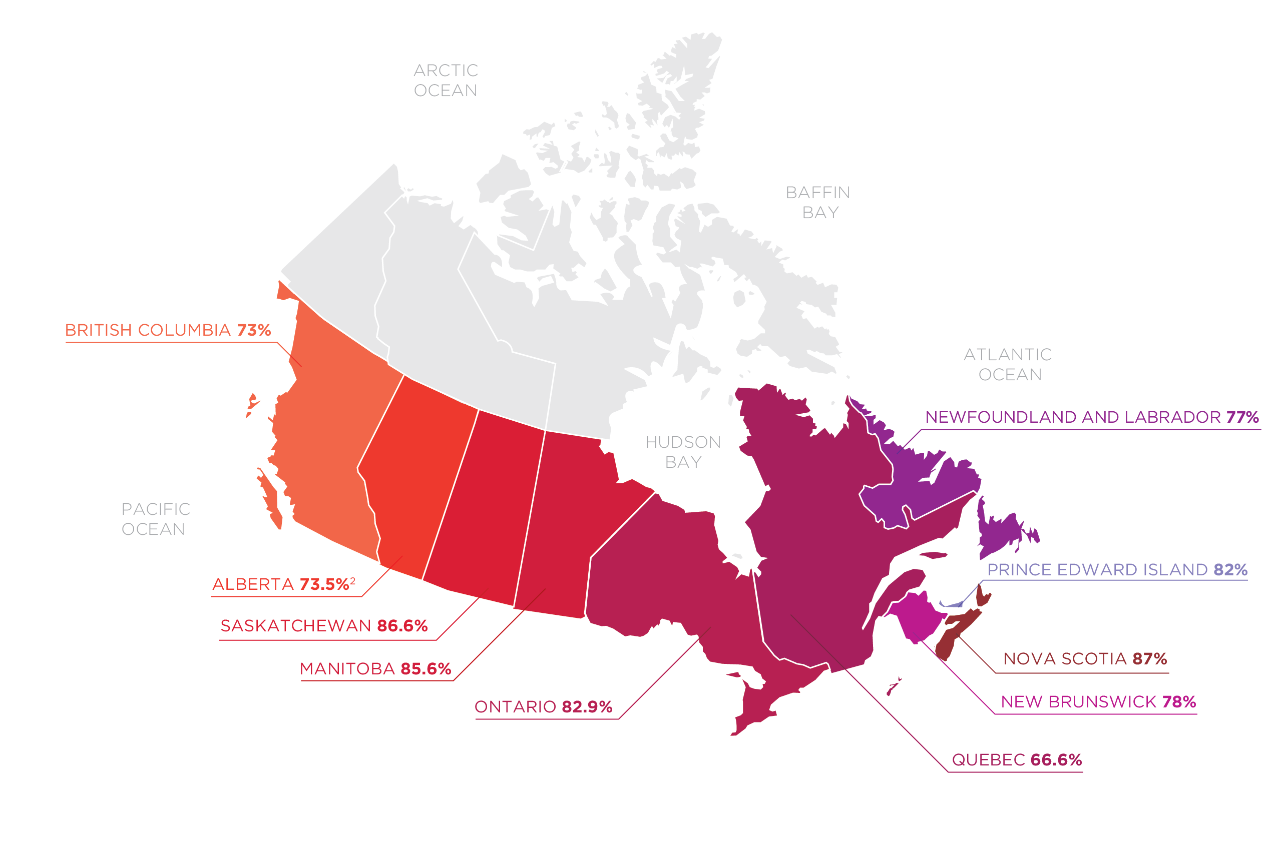

PREVALENCE OF GAMBLING

Across the World

The prevalence of gambling in the adult population varies across the world between 48% in France and 78% in the United States1 and Finland.

Specifications: 1 Lifetime prevalence.

2 In Canada, the last national survey using a representative sample across provinces was conducted in 2002. Based on data derived from the Canadian Community Health Survey (cycle 1.2), the prevalence rate of gambling participation was estimated at 76%.

3 Mean of provincial prevalence rates.

4 Prevalence includes speculative investments, but excludes raffles.

The average prevalence rates of gambling participation across Canada is estimated at 79.2% among the adult population and varies between provinces1; from 67% in Quebec to 87% in Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan.

Specifications: 1 Data extracted from the most recent prevalence studies conducted in each province or territory.

2 Prevalence excludes raffles.

Methodology

A review of national surveys was conducted to estimate the prevalence of gambling between 2001 and 2013, in different countries, in Canada, as well as in each Canadian province. Percentages correspond to the prevalence in the past 12 months, unless stated otherwise. The methodological details of each survey are available in the original documents cited in the references.

References

Africa

South Africa

Collins, P. & Barr, G. (2009). Gambling and Problem Gambling in South Africa: A Comparative Report. A report prepared for the South African Responsible Gambling Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.responsiblegambling.co.za/media/user/documents/NRGP%20Comparative%20Report%20-%20June%202009.pdf.

Asia

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2012). The Study of Hong Kong People's Participation in Gambling Activities. Department of Applied Social Sciences. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Commissioned by the Secretary for Home Affairs, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. March 2012. Retrieved from http://www.hab.gov.hk/file_manager/en/documents/policy_responsibilities/others/gambling_report_2011.pdf.

Singapore

National Council on Problem Gambling (2012). Report of Survey on Participation in Gambling Activities among Singapore Residents, 2011. Singapore: Author. February 23, 2012. Retrieved from http://app.msf.gov.sg/Portals/0/Summary/research/EDGD/Gambling%20participation%20survey%202011.pdf.

South Korea

Williams, R.J., Lee, C-K., & Back, K-J. (2013). The Prevalence and Nature of Gambling and Problem Gambling in South Korea. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 821–834.

Europe

Belgium

Druine (2009). Belgium. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

Denmark

Bonke, J., & Borregaard, K. (2006). The Prevalence and Heterogeneity of At-Risk and Pathological Gamblers - The Danish Case (Working Paper 15: 2006). Danish National Institute of Social Research. Retrieved from http://www.sfi.dk/publications-4844.aspx?Action=1&NewsId=168&PID=10056.

Estonia

Laansoo & Niit (2009). Estonia. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

Finland

Turja, T., Halme, J., Mervola, M., Järvinen-Tassopoulos, J., Ronkainen, J-E. (2012). Suomalaisten Rahapelaaminen 2011 [Finnish Gambling 2011]. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare.

France

Costes, J-M., Pousett, M., Eroukmanoff, V., le Nezet, O., Richard, J-B., Guignard, R., Beck, F., & Arwidson, P. (2011). Les Niveaux et Pratiques des Jeux de Hasard et D'argent en 2010. French Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and the National Institute for Prevention and Health Education. September 2011. Retrieved from http://www.inpes.sante.fr/30000/pdf/tendances77.pdf.

Germany

Berater, W., Haase, H. & Puhe, H. (2011). Spielen mit und um Geld in Deutschland. TNS Emnid. October 2011. Retrieved from http://awi-info.de/userupload/files/emnid-studie-2011- ergebnisse.pdf.

Great Britain

Wardle, H., Moody, A., Spence, S., Orford, J., Volberg, R., Jotangia, D., Griffiths, M., Hussey, D., & Dobbie, F. (2011). British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. Prepared for The Gambling Commission. London: National Centre for Social Research. Retrieved from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/British%20Gambling%20Prevalence%20Survey%202010.pdf.

Holland

Goudriaan et al (2009). The Netherlands. In G. Meyer, T. Hayer, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Problem Gambling in Europe: Challenges, Prevention, and Interventions. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1.

Hungary

Kun B., Balázs H., Arnold, P., Paksi, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2011). Gambling in western and eastern Europe: The example of Hungary. Journal of Gambling Studies. doi:10.1007/s10899-011-9242-4.

Iceland

Ólason, D.T. (2009). Gambling and Problem Gambling Studies among Nordic Adults: Are they Comparable? Conference presentation @ 7th Nordic Conference, Helsinki, Finland, May, 2009.

Italy

Barbaranelli, C. (2010). Prevalence and Correlates of Problem Gambling in Italy. 8th European Conference on Gambling Studies and Policy Issues, September 14-17, 2010.

Norway

Bakken, I. J., Götestam, K. G., Gråwe, R. W., Wenzel, H. G. & Øren, A. (2009). Gambling behavior and gambling problems in Norway 2007. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50, 333-339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00713.x

Sweden

Abbott, M.X., Romild, U., & Volberg, R.A. (2013). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Sweden: Changes Between 1998 and 2009. Journal of Gambling Studies, DOI 10.1007/s10899-013-9396-3.

North America

Canada

Canadian Gambling Digest. (2012-2013). Toronto, ON: Canadian Partnership for Responsible Gambling. Retrieved from http://www.responsiblegambling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/20140725_canadian_gambling_digest_2012-13.pdf?Status=Temp&sfvrsn=2

Marshall, K., & Wynne, H. (2003). Fighting the odds. Perspectives on labour and income, 4(12), 5-13.

United States

Kessler, R.C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N.A., Winters, K.C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 38(9), 1351-1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900

Pacific

Australia

Gainsbury et al. (2013). How the Internet is Changing Gamblng: Findings from an Australian Prevalence Survey. Journal of Gambling Studies. DOI 10.1007/s10899-013-9404-7

New Zealand

Mason, K. (2009). A Focus on Problem Gambling: Results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/focus-problem-gambling-results-2006-07-new-zealand-health-survey.

Province

Alberta

Williams, R.J., Belanger, Y.D., & Arthur, J.N. (2011). Gambling in Alberta: History, Current Status, and Socioeconomic Impacts. Final Report to the Alberta Gaming Research Institute. Edmonton, Alberta. April 2, 2011. Appendix A: 2008 and 2009 Alberta Population Surveys.

British Columbia

Ipsos-Reid & Gemini Research. (2008). British Columbia Problem Gambling Prevalence Study. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. Retrieved from https://www.gaming.gov.bc.ca/reports/docs/rpt-rg-prevalence-study-2008.pdf.

Manitoba

Lemaire, J., MacKay, T., & Patton, D. (2008). Manitoba gambling and problem gambling 2006. Winnipeg, MB: Addictions Foundation of Manitoba. Retrieved from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba web site: http://www.afm.mb.ca

New Brunswick

MarketQuest Research. (2010). 2009 New Brunswick Gambling Prevalence Study. Prepared for Department of Health and New Brunswick Lotteries and Gaming Corporation, Government of New Brunswick. Fredericton, NB.

Newfoundland and Labrador

MarketQuest Research (2009). 2009 Newfoundland and Labrador Gambling Prevalence Study. Prepared for Department of Health and Community Services, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John's, NL: Department of Health and Community Services. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publications/2009_gambling_study.pdf.

Northwest Territories

NWT Addictions Report. Prevalence of alcohol, illicit drug, tobacco use and gambling in the Northwest Territories. (2010). Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. Retrieved from http://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/default/files/nwt_addictions_report.pdf.

Nova Scotia

Focal Research Consultants (2008). 2007 Adult Gambling Prevalence Study. Halifax, NS: Nova Scotia Health Promotion and Protection. Retrieved from http://www.nsgamingfoundation.org/uploads/Adult_Gambling_Report.pdf.

Ontario

Williams, R.J. & Volberg, R.A. (2013). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Ontario. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. June 17, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.uleth.ca/dspace/handle/10133/3378.

Prince Edward Island

Doiron, J. (2006). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Prince Edward Island. Submitted to Prince Edward Island Department of Health. Retrieved from http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/doh_GambReport.pdf.

Quebec

Kairouz, S., & Nadeau,L. (2014). Portrait du jeu au Québec: Prévalence, incidence et trajectoires sur quatre ans. Montreal, QC: Université Concordia. Retrieved from http://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/concordia/research/lifestyle-addiction/docs/ENHJEU-QC%202012%20-%20RAPPORT%20FINAL%20FRQ-SC%20_19.02.2014%20%281%29.pdf.

Saskatchewan

Wynne, H. (2002). Gambling and Problem Gambling in Saskatchewan: Final Report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.sk.ca/adx/aspx/adxGetMedia.aspx?DocID=317,94,88,Documents&MediaID=166&Filename=gambling-final-report.pdf.