Olympic training is punishing. “It’s a full-time job,” says Bilodeau, who’s an accounting student at Concordia’s John Molson School of Business. Sochi will be the 26-year-old’s third Olympics and probably his last. The Games have already left an indelible mark on the skier. “When I was 18, in my first Olympic Games, I wasn’t concerned about the same things I am now. Everything changes.”

In a sport as precise and dangerous as moguls skiing, gold medal performances must be near flawless. The pace is gruelling. Skiers complete a dozen turns with complex aerial acrobatics. Runs last less than 30 seconds — a flash, yet plenty of time for career-ending injuries.

“In skiing in general, one injury we’re really worried about is the torn anterior cruciate ligament [ACL, located in the knee],” says Geoff Dover, assistant professor in the Department of Exercise Science. He’s also a member of Concordia’s PERFORM Centre, a nexus for research in exercise science, psychology and behavioural medicine. “In some big ski resorts they see a torn ACL a day.”

Mogul skier Alex Bilodeau works with a sports psychologist to improve his performance readiness and self-understanding.

Credit: Martin Girard

Mogul skier Alex Bilodeau works with a sports psychologist to improve his performance readiness and self-understanding.

Credit: Martin Girard

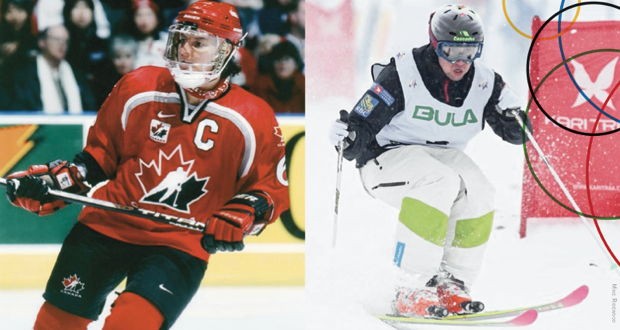

Gold medal winners Alex Bilodeau, right, and former concordia stinger Therese Brisson, who won with the 2002 Canadian women’s hockey team. The current squad features forward Caroline Ouellette, an assistant coach with the stingers, and assistant coach Lisa Jordan, BA 91; Julie Healy, BSc 83, is manager of team services for the Canadian Olympic committee.

Credit: Mike Ridewood

Gold medal winners Alex Bilodeau, right, and former concordia stinger Therese Brisson, who won with the 2002 Canadian women’s hockey team. The current squad features forward Caroline Ouellette, an assistant coach with the stingers, and assistant coach Lisa Jordan, BA 91; Julie Healy, BSc 83, is manager of team services for the Canadian Olympic committee.

Credit: Mike Ridewood

Geoff Dover, an exercise science professor, at Concordia’s PERFORM centre. The centre’s research includes looking at why some people feel more pain than others and how that affects recovery.

Credit: Concordia University

Geoff Dover, an exercise science professor, at Concordia’s PERFORM centre. The centre’s research includes looking at why some people feel more pain than others and how that affects recovery.

Credit: Concordia University