The power of the page

Retranscription of la Bible – nouvelle traduction, 2009-present and La Bible – Nouvelle traduction, by Simon Bertrand. | Courtesy of the artist and Galerie René Blouin, Montreal

Retranscription of la Bible – nouvelle traduction, 2009-present and La Bible – Nouvelle traduction, by Simon Bertrand. | Courtesy of the artist and Galerie René Blouin, Montreal

When was the last time you read something off of a page without getting distracted?

No, not a web page, not a Kindle and definitely not a smartphone, but a real book — you know, the kind made of paper?

Katrie Chagnon, Max Stern curator of research for the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery, has been asking herself — and others — that question a lot over the past year.

“There were so many discourses about the decline of reading, the threat to our attention abilities, the fact that books were kind of disappearing,” Chagnon says.

“I was kind of curious about the nostalgic tone of those claims, and on the other hand I was noticing an increasing interest in the art world about reading.”

Her musings led her to curate a new exhibition, Reading Exercises, which begins with a vernissage at 5:30 p.m. on November 18. The show features 12 works from Canadian and international artists, including Brendan Fernandes and Simon Bertrand.

The latter will be displaying one of his ongoing works, which he began in 2009: a laborious handwritten re-transcription of the Bible. “Each transcription error is crossed out, the correction is made and the text continues,” he explains in his statement about the project.

“These deletions trace the passage of the book through the hand and onto the paper. They perforate the text and hold it in suspense. They arise from the gesture’s awkwardness, imprecision and incapability.”

Another of the pieces on display will be #ReadtheTRCreport, a video project created by Erica Violet Lee, Joseph Murdoch-Flowers and Zoe Todd. It consists of a collection of 140 YouTube videos showing people reading sections of The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Interim Report that address the forced assimilation of Aboriginal people in Canada by means of the residential school system.

The idea is to encourage Canadians to engage with the extensive document. “It’s rare for us to take the time to read something that will take a long time,” Chagnon says.

To her, #ReadtheTRCreport demonstrates the power of collective reading — an idea that informs several of the other pieces that will be on display at the Ellen Gallery.

“Contemporary artists take reading as kind of an experimental and critical space,” she says.

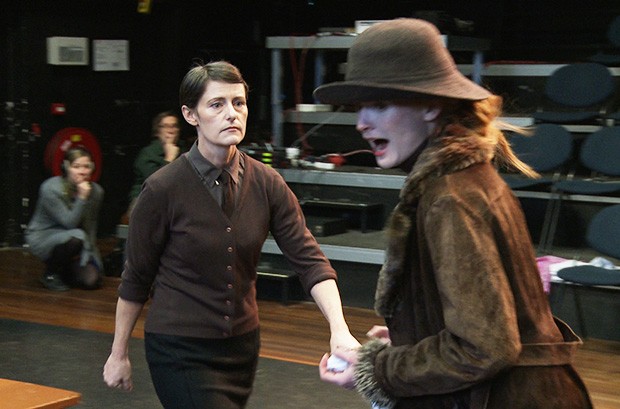

A Romance in Five Acts and Twenty-one Englishes, by Nicoline van Harskamp. 2015. Video of the performance: Jelle van der Does. | Courtesy of the artist with the support of Mondriaan Fund

A Romance in Five Acts and Twenty-one Englishes, by Nicoline van Harskamp. 2015. Video of the performance: Jelle van der Does. | Courtesy of the artist with the support of Mondriaan Fund

Another collection of videos by Dutch artist Nicoline van Harskamp (see trailer here), explores the idea of how English became the world’s language of choice and how it’s changed as a result of that. “It’s become a very heterogeneous language,” Chagnon says.

In 2014, van Harskamp conducted a collective, intercultural language experiment based on 21 translations of the play Pygmalion: A Romance in Five Acts, written by George Bernard Shaw in 1912.

Van Harskamp asked participants to re-translate the texts from their native tongues back into English. This resulted in the new version of the play, titled A Romance in Five Acts and Twenty-one Englishes.

The video installation featured in the exhibition is based on a recording of the play, performed on stage by English actors in Amsterdam in 2015, as well as the rehearsals held prior to the performance.

The main video work presents the actors’ struggle to produce English sentences and words that seem utterly foreign to them.

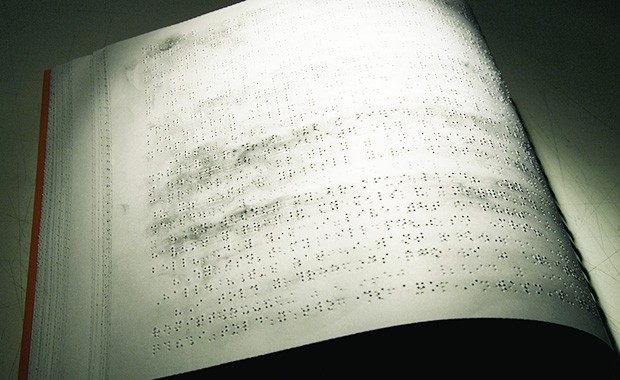

Index/Criminal Offenses, Chapter 11, by Ricardo Cuevas. 2008-2015. Braille book, graphite. | Courtesy: the artist

Index/Criminal Offenses, Chapter 11, by Ricardo Cuevas. 2008-2015. Braille book, graphite. | Courtesy: the artist

Index/Criminal Offenses, Chapter 11 by Mexican artist Ricardo Cuevas is a protest against the post-9/11 USA Patriot Act, which enables the American Government to, among other things, look into what books a suspect has checked out at American public libraries.

The work involved asking people with visual impairments to read a Braille book.

“One of the first pages of a book (the index) was covered with several layers of graphite,” writes Cuevas on his blog. The readers’ blackened fingertips left traces on the subsequent pages of the book, creating a record of what they had just read.

The reconceptualization of reading as a mass activity isn’t much of a stretch, considering how the internet has made much of what is written in this day and age a matter of public record.

Yet, as Reading Exercises ascertains, reading a book — cracking the binding, flipping the pages, smelling the curious aroma of ink and paper — often remains a private act.

“It’s not only a personal, individual practice, solitary and concentrated,” Chagnon says. “If we get out of that traditional concept, we can look at it as a collective act.”

Reading Exercises opens at the Ellen Gallery (1400 De Maisonneuve Blvd.) with a vernissage on November 18 from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. and remains on display until January 23, 2016.

Reading Exercises opens at the Ellen Gallery (1400 De Maisonneuve Blvd.) with a vernissage on November 18 from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. and remains on display until January 23, 2016.