Trafficking ideas

Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965-1980 is a two-part exhibition at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery that attempts to track the influence of the powerful conceptual art movement on Canadian artists during this important early period.

The exhibition is a joint effort of curators from across Canada, including Michèle Thériault, director of the Ellen Art Gallery and Vincent Bonin, an independent curator who worked with Thériault on the Montreal component.

“This exhibition is about when conceptual art began appearing and how it manifested itself,” Thériault says.

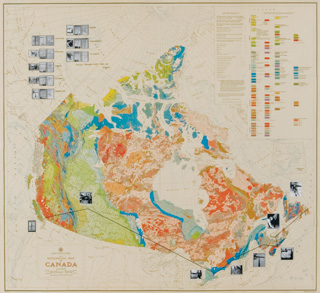

The six Traffic curators met over several years to develop the exhibition, which was displayed for the first time at the art galleries of the University of Toronto in the fall of 2010. The curators decided to present the works according to their cities of origin, to show the various forms conceptual art adopted in each place in relation to the global conceptual movement and to what was happening elsewhere in Canada.

Part One of the Traffic exhibition, which runs until Saturday, February 25, features conceptual art from Montreal, Toronto, Guelph and London, Ont. Part Two, featuring conceptual art from Halifax, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary, Vancouver and the Arctic, runs from Friday, March 16 to Saturday, April 28.

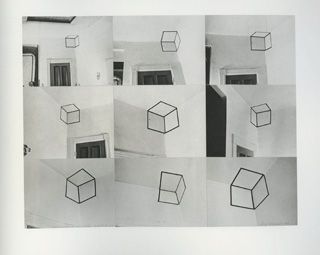

Artists, influenced by a changing media landscape and the political and social unrest of the 1960s, gravitated towards a new way of thinking about art: that it wasn’t just about objects, but ideas as well. It could manifest itself in language and in actions, and these could be recorded for exhibition in language, on film, and in pictures.

The history of conceptual art in Canada is fragmented, and has only received cursory attention as a national movement from art historians, perhaps because it’s harder to trace through physical artifacts.

“It’s the first exhibition to bring out this stuff,” Thériault says. “In our case, in Montreal, there had been very little primary research done, and we had to research in archives to see who was working at the time.”

The overall sense Thériault got during her research was that the movement did not receive the same recognition in Montreal as it did in other Canadian cities such as Halifax, Toronto and Vancouver. “One of the reasons could be that the legacy of the painting tradition in Quebec is very, very strong.”

Even so, many well-known Quebec artists did create interesting conceptual pieces. “Françoise Sullivan did a walk between the two major museums as a way of locating the artist physically between the two institutions, and locating the artwork in a walk, in a body in movement, so outside of the walls of the institutions.”

During her research, Thériault and Bonin also discovered a forgotten key conceptual art event, held at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia’s downtown campus) and the Saidye Bronfman Centre in 1971, called 45° 30' N, 73° 36' W (the latitude and longitude of Montreal). The exhibit was put together by artists Bill Vazan, Arthur Bardo and Gary Coward.

“Although it didn’t have much of an impact at the time, it comes out as being the most purely conceptual event of the time,” Thériault says. The catalog for the show was put together using index cards, which were given out in small plastic bags. On them were statements from artists rejecting older notions of art, such as this one by artist Douglas Huebler: “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add anymore.”

Another, a statement by British artist Keith Arnatt, reads: “The content of my work is the strategy employed to ensure that there is no content other than the strategy.”

“We are getting rid of ownership, substituting use,” says another written by famed American conceptualist John Cage.

The cards are displayed on a table in the Traffic exhibition, and when read together signify a rejection of the status quo, and a desire for a fresh start.

That early exhibition led to the creation of Véhicule Art Inc., an artist-run organization that showcased conceptual and multidisciplinary artists. Finally, Montreal’s avant-garde artists had a place to call home.

“One can equate conceptual art with experimentation, and that’s why it evolved very much in artist-run centres all across Canada,” Thériault says. “Those places were created by artists to experiment, which they couldn’t do in the institutions. For instance, an artist pouring clay on a gallery floor was not something an institution would allow. In Montreal, that was done at Véhicule.”

A number of events are held in conjunction with the exhibition on January 28, February 1 and 8. Click the events link for more details.

Related links:

• The Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery

• Traffic exhibition

• Events in conjunction with Traffic