The breadth of the school’s program is a testament to Kenneally’s ingenuity. Students enjoy courses in literature, history, political science, economics, geography, arts and popular culture, women’s studies and the Irish language.

“A degree in Canadian Irish Studies will allow students to explore the history and rich culture of Ireland and its diaspora and learn about complicated subjects related to colonialism, nationalism, war, religion and more,” Kenneally says. “Ireland presents a classic case study of these contentious issues. And its multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach prepares students for the complexity of our globalized world.”The remaining 15 credits are drawn from a broad selection of Irish-themed electives including courses on James Joyce, Irish film, theatre, the Irish in Montreal, the Great Irish Famine, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Highlights of Irish Literature and Celtic Christianity.

He adds that students also benefit from studying in a small school, with a hands-on mentoring environment, within a large, urban university.

Amanda Leigh Cox, MA (trans.) 09, who is pursuing an interdisciplinary PhD in humanities, commends the wide range of experts and scholars. “They make it a fully rounded experience for students and provide a global view of Irish culture, historically and in the present. It’s a very progressive and vibrant environment, and we’re allowed to stretch our wings and follow what interests us.”

As the program grew, Kenneally drew on professors from across the university, often, but not always, with Irish ancestry. Now, thanks to successful fundraising, the school has six full-time professors.

Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin (pronounced Garode O-allveronn) is an Irish anthropologist and ethnomusicologist and the first holder of the Johnson Research Chair in Quebec and Canadian Irish Studies. Gavin Foster is an expert on oral history, particularly of the final phase of the Irish Civil War (1922-23). Jane McGaughey studies the Irish diaspora in Canada, the United States and Britain, especially the Orange Lodge. Susan Cahill is interested in Irish children’s writing and the Irish girl as a literary and cultural figure. Rhona Richman Kenneally, who is based in the Department of Design and Computation Arts, is a fellow of the school. She teaches a course on Irish Domestic Space and is editor of the Canadian Journal of Irish Studies.

Kenneally himself focuses on modern and contemporary Irish literature. As the principal Canadian investigator of an international team studying memory, identity and representations of the past in Ireland and Quebec, he is looking closely at depictions of the Quebec Rebellion of 1837.

Beautiful but difficult language

Studying the Irish in Canada offers rich rewards for the ambitious scholar. Few formal studies have been done on their influence, and records are scattered or missing. To give just one example, Concordia emeritus professor of geography Patricia Thornton and a colleague from McGill University pored over Montreal records and statistics, and what they found contradicts the stereotype of the disreputable Irish immigrant. On the contrary, they found a close-knit, upwardly mobile community whose members helped one another.

This year’s Ireland-Canada University Foundation Visiting Scholar is Seaghan Mac an tSionnaigh, a young expert on Irish language. This beautiful but difficult tongue is a requirement in some Irish Studies programs, although not at Concordia. Nevertheless, Kenneally says that about 20 students love it and are specializing in it.

The school also supports graduate students. Heather Macdougall, who just finished her interdisciplinary PhD in humanities, says, “It offers scholarships, encourages participation in conferences and provided me opportunities to work as a teaching assistant and then as an instructor. I was able to design and teach two new courses on Irish and Northern Irish film, both of which were quite popular.”

One of the benefits of being associated with the school is the opportunity to meet people from Ireland. A steady stream of distinguished writers, filmmakers and scholars, even a celebrity chef, have visited Concordia to inform the general public, teach students and share their research. “I really appreciated the guests that Irish Studies brings to Concordia,” Macdougall says. “It helps expose students to other perspectives.”

The traffic also goes the other way. Kelly Norah Drukker, BA 99, is a young poet and non-fiction writer who won a St. Patrick’s Society Scholarship. She’s writing about the time she spent on the island of Inis Mór, off the coast of County Galway. “When I decided to return to school to pursue an MA in English and creative writing, it was essential that I be able to continue my engagement with Irish culture as a part of my studies,” Drukker says. “The school has an intimate, supportive atmosphere that makes me feel glad to be a part of it.”

From left: Alumnus David Scott, former foundation chair Brian Gallery, Principal Michael Kenneally and Ray Bassett, ambassador of Ireland to Canada. | Photo: Ashley Fraser

From left: Alumnus David Scott, former foundation chair Brian Gallery, Principal Michael Kenneally and Ray Bassett, ambassador of Ireland to Canada. | Photo: Ashley Fraser

James Joyce

James Joyce

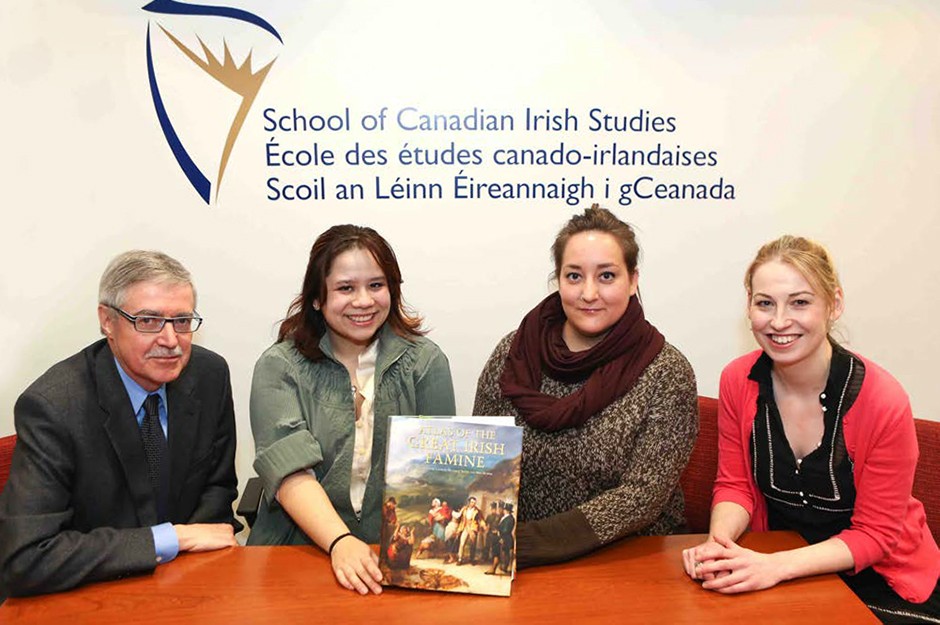

From left: Michael Kenneally, principal of the school of Canadian Irish studies, Angela Olaguera, Camille Harrigan and Susan Cahill, assistant professor of Irish literature. In January, the school presented copies of the atlas of the great Irish famine to Olaguera and Harrigan, the first students to enrol for Concordia’s major in Canadian Irish studies. | Photo: Joseph Dresdner

From left: Michael Kenneally, principal of the school of Canadian Irish studies, Angela Olaguera, Camille Harrigan and Susan Cahill, assistant professor of Irish literature. In January, the school presented copies of the atlas of the great Irish famine to Olaguera and Harrigan, the first students to enrol for Concordia’s major in Canadian Irish studies. | Photo: Joseph Dresdner