STEM SIGHTS: The Concordian who investigates species conservation with the Cree community

Mistassini Lake, a remote place about 800 kilometers north of Montreal, is sometimes referred to as “fly-in” country by those who visit it for the fishing tourism that has boomed there in the last 15 years.

For centuries, the Cree Nation of Mistissini has harvested the lake’s fish populations for subsistence, and they currently manage its fishing tourism. The community is keenly interested in the conservation of these fisheries.

Ella Bowles, a postdoctoral researcher working with Dylan Fraser’s lab in the Department of Biology at Concordia, studies conservation genomics in fish. Her research seeks to understand how harvesting fish impacts these populations on a genetic level, which in turn would help to inform sustainable harvesting practices.

A statistically significant reduction in both the length and mass of walleye populations living in Mistassini Lake occurred during the rise of the fishing tourism industry in the region. Bowles’ postdoctoral work is determining whether there has been an associated reduction in genetic diversity among these populations.

She is using knowledge gleaned from her research to collaborate with the Cree Nation of Mistissini in its goal of resource conservation. Integrating scientific information with traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), she hopes to facilitate a comprehensive, community-based approach to population management.

‘The goal is to ensure the fish stocks are available for generations to come’

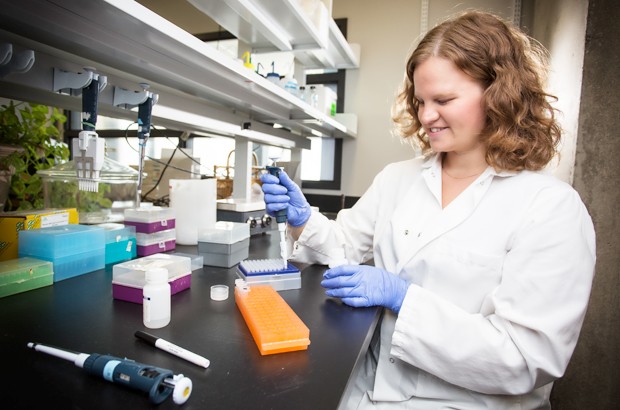

How does this specific image (top) relate to your research at Concordia?

In this photo, I am extracting DNA that I will later sequence to generate thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

An SNP is a unit of information that I use to make inferences about the fish populations I am studying. I can determine things like how many populations or genetically distinct groups there are and whether populations have evolved and changed over time.

I can also see what parts of the genome might be driving that change, whether populations may be under selection within the genome, how much interbreeding is occurring between populations and — depending on the type of fish I am investigating and how much we know about them — information as precise as a fish’s river of origin.

What is the hoped-for result of your project?

To arrive at a clear understanding as to whether or not there have been any changes over time in the populations of a number of fish species that are both harvested for subsistence and fished recreationally in Mistassini Lake. Last year I worked only on walleye, but in the coming two years I'll also be working on lake trout, brook trout and northern pike.

What impact could you see it having on people's lives?

All of the work that we are doing on this project is either for, or in collaboration with, the Cree Nation of Mistissini. They use this information to guide the management and harvesting of certain fish species within Mistassini Lake. This is with the intention of maintaining stocks to ensure that the resource is available for generations to come.

What are some of the major challenges you face in your research?

A major challenge for my work is how rapidly the methodology changes, both in the molecular lab and at the analysis stage. For example, when I began grad school 10 years ago, most labs used between one and two dozen microsatellite markers. These are the locations in an organism’s genome that provide information about evolutionary processes that shaped their geographic distribution.

Now, the norm is to use thousands of markers distributed throughout a given genome. This means that biologists have to rely increasingly on computer programming to navigate the data. The software used for this kind of analysis is always changing, so it is an added difficulty to be constantly learning new programs, both in terms of publishing before work becomes dated and the amount of information you must retain.

What are some of the key areas where your work could be applied?

It applies directly to resource conservation. My particular research project is important to the Cree Nation of Mistissini but more broadly I am using both scientific knowledge and TEK to study the fish species in the area. The use of interdisciplinary methods for resource conservation is growing, but much more is needed.

My methods and the way that I interpret and apply the results may therefore be able to serve as a blueprint for others who would like to use TEK to complement their scientific methods, such as wildlife managers.

What person, experience or moment in time first inspired you to study this subject and get involved in the field?

I have been interested in environmental issues since I was very young, perhaps influenced by my “concerned citizen” parents. But also, my bachelor of science degree at the University of British Columbia used an evolutionary framework, which I particularly enjoyed.

During and after my undergraduate education I was also involved in molecular cancer research. I really enjoyed this work and it introduced me to the power of molecular biology as a tool.

While taking a biology of marine fishes course at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, I became enchanted with the biodiversity of fish. I was simultaneously shocked by the state and trajectory of our fisheries and struck by the understanding that molecular tools could bring to these problems. That was really the start of my current path.

How can interested STEM students get involved in this line of research? What advice would you give them?

Volunteer! The best advice that I have for students is to read about some of the researchers at their institution (or other institutions) and contact them about opportunities to volunteer or work in their labs. Paid work is ideal, of course, but any contact with research will give you a feel for whether you like it or not and what kind of work you enjoy most.

What do you like best about being at Concordia?

There are two things that make being at Concordia truly great.

First, my supervisor and lab are a wealth of knowledge, often about things that are relatively new to me and complementary to my work. My colleagues are quite generous with their time as well, which has resulted in productive collaborations.

Second, I am grateful to have full access to the GradProSkills workshops as a postdoc. I have taken several courses, including on grammar, project management, literature review and French conversation. They have all been excellent, both in content and presentation.

Are there any partners, agencies or other funding/support attached to your research?

Yes! I am grateful to have recently been awarded a Mitacs Elevate fellowship. This is a collaborative project between Concordia, Mitacs and Niskamoon Corporation, who are funding a majority of the work. Niskamoon is a not-for-profit agency that facilitates work between the Cree people and Hydro-Quebec.

They support multiple environmental and cultural projects that encourage sustainable resource use and autonomy for the Cree people. My work helps with all of those things, so it fit nicely within their mandate. Being able to engage in on-the-ground conservation through this fellowship is the realization of my dream.

Find out more about Concordia’s Department of Biology.