Director, cinematographer, mentor: Concordian Martin Duckworth wins Quebec’s highest honour

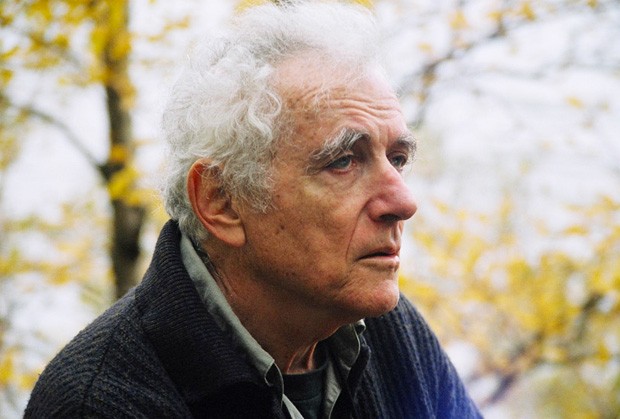

“You have to be a team player to make good film,” says Martin Duckworth, filmmaker and long-time instructor at Concordia’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema. | Image courtesy of Les productions pleiades

“You have to be a team player to make good film,” says Martin Duckworth, filmmaker and long-time instructor at Concordia’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema. | Image courtesy of Les productions pleiades

One day last summer, Martin Duckworth’s phone rang.

It was Hélène David, Quebec’s Minister of Culture and Communications, informing the long-time Montreal documentary filmmaker and part-time Concordia instructor that he had won a Prix du Québec — specifically, the $30,000 Prix Albert-Tessier for an outstanding career in cinema.

“It was kind of a shock because that prize has gone to people I’ve admired all my life,” says the 82-year-old Duckworth. Previous winners include Denys Arcand, Norman McLaren and Claude Jutra.

As cinematographer of 100 films and director of 30, Duckworth has championed countless social causes on and off the screen from the 1960s onwards. For nearly a quarter century, from 1990 to 2012, he also memorably edified the next generation at Concordia’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema.

But with characteristic humility, Duckworth says he can’t imagine what he’s done to merit placement on the same pedestal as great Quebecers like Gilles Groulx.

Jocelyne Clarke — a filmmaker and the wife of the late Magnus Isacsson, a long-time friend and collaborator of Duckworth’s — believes he is more than worthy.

“I can’t think of anyone more deserving than Martin Duckworth who, in addition to being an exceptional cameraman and director in his own right, has been a tireless supporter of others, and a mentor to emerging filmmakers,” Clarke says.

Duckworth’s decades of community activism and participation in peace and human rights movements have made him a model citizen, Clarke notes.

“It is, however, an indication of his humility as a person and regard for others that he would say he doesn’t deserve this prize.”

‘A real humanitarian’

Duckworth comes from a long line of activists.

“My mother was one of the founding members of the [peace advocacy group] Voice of Women,” he says. She and his father were pacifists, in a family tradition that Duckworth traces back to Nicholas Austin, an American Quaker who settled in the Eastern Townships in the 1700s.

“He’s very much present in our family history. We often refer back to him, and to his Quaker ideals.”

Duckworth first became politicized in the early half of the 1960s, soon after getting a job as a cameraman at the National Film Board of Canada.

Professional and political commitment took him to Vietnam in 1969 (Sad Song of Yellow Skin); to Germany (Return to Dresden) and Russia (Our Last Days … in Moscow) in the 1980s; and to Afghanistan in the early 2000s (Return to Kandahar).

In Fouad's Dream (2012), Duckworth followed his Palestinian friend's efforts to buy back a family hotel in Haifa, Israel.

“Martin is a real humanitarian,” says Daniel Cross, a friend and associate professor of film production at Concordia.

‘You knew they were Martin’s students’

As a teacher, Duckworth helped his students become caring citizens: Cross believes he sought to develop consciences and social voices, as well as cinematic technique.

“My main message was filmmaking is not a one-man enterprise like the other arts,” Duckworth says. “You have to be a team player to make good film.”

As Cross recalls, lessons often stretched supper at Duckworth’s Mile End home, which he shares with his wife, photographer Audrey Schirmer.

“Martin’s forte was ‘Filmmaking I,’” Cross says. “When you would get Martin’s students in ‘Filmmaking II,’ you knew they were Martin’s students.

‘I feel quite happy’

What’s next, after a Prix du Québec? Duckworth may have retired from teaching, but he still keeps his hand in the industry.

The $30,000 prize money will go to a film on Édouard Lachapelle, an art historian and friend. Duckworth has shot about half of it, at his own expense; securing funding was difficult because Lachapelle isn’t famous.

“He’s a great teacher,” Duckworth says. “Great teachers don’t become known, so I want to make him known.”

Duckworth received his Prix du Québec last month in Quebec City, surrounded by family. As the father of seven and grandfather of 11 blithely recollects, the event turned into a multi-birthday celebration for four relatives.

To Duckworth, it was the perfect way to receive the award. “I felt quite happy, and I have ever since.”

Find out more about film studies and film production at Concordia’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema.